COMPOSING GESTURE-TOPICS: A SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO VILLA-LOBOS’ AFRICAN FOLK DANCES.

Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil

son.bass@gmail.com; cleisson.melo@helsinki.fi

Abstract

One of the most important Brazilian composers, Heitor Villa-Lobos has developed a remarkable creative and exuberant language. Understanding his style, ideology, technique, strategies, and so on, remains a challenge. This paper is concerned to offer a reconsideration about Villa-Lobos’ music and its relationship with the Brazilian musical hybridism to identify the use of the Brazilian nationalistic elements as a step to realize his compositional ideology.

An existential semiotics-based analytical approach should be a powerful means to highlight Villa-Lobos’ compositional ideology, especially to explore of the mechanics of composition and expression in a particular genre known as “dance”, in relation to specific Brazilian national and nationalist creative features emerging from his particular creative processes which allows identify cultural-musical signs into the Brazilian orchestral music. To demonstrate it, this paper is trying to portray his approach of the use of representative components in his musical gestures writing as sound movements provided with meanings through cultural experience, via the analysis of the first movement ofDanças caracteristicas Africanas (African Folk Dances). This music was one of the first attempts to conduct to the “musical miscegenation” in the way to building the “alma brasileira” (Brazilian soul) as the Brazilian musical language of concert.

1. Introduction

One of the most important Brazilian composers, Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959), developed a remarkable creative and exuberant language. In general, his music is associated with the emerging nationalism of Brazil in the turn of the 20th century. Nevertheless, understanding his style, ideology, technique, and strategies remains a challenge.

Villa-Lobos lived in Paris for a few years during the 1920’s, his time in Paris provided him a close experience with European modernism and composers. His Brazilian culturally mixed experience associated with the styles and fashions in Europe in those days was significant to the rise of his personal style. Certainly this distinct view of “different” approaches of modernisms gave him tools to influence the modern Brazilian musical language through that cultural miscegenation.

Villa-Lobos’ involvement with popular music and folklore of Brazil lent him unaccountable melodies, rhythms, sounds combinations, and so on. This involvement can be clearly noticed in many of his works. This cultural/musical hybridism seems to be relevant to his compositional attitude, since he was engaged with Brazilian modernism and representation of national elements.

Consequently, the strengthening of Brazil’s national borders set off discussions about nationalism, national culture, and identities. So, deriving from the diverse social processes that established the roots of Brazilian music, there was a “demand for new theories and critical tools that could cover more subtlety aspects in different contexts” (David 2006: 243). Brazil’s diverse soundscape is the framework that fomented the search for the ethos of the Brazilian musical aesthetics.

However, some questions need to be addressed. What legitimizes a Brazilian musical aesthetic? Does the compositional process adopted by Villa-Lobos follow a formal aesthetic or set of rules? Does the national imaginary (and symbolic negotiation of it) follow a unique ideological form within the compositional process? Is there a way to keep a “central signification” (Debrun 1990: 39) in Brazilian musical discourse? Regardless of the uncertainly suggested by these questions, it is difficult to deny that there are sound traces in Brazilian music that help identify it as Brazilian musical language (signs).

Identifying national markers in music is certainly a complex endeavor. Following the proposition by Paulo Salles (2013), “national” can be defined as “marked”, while “no-national” or “universal” can be classified as “unmarked”. So, “precisely in this asymmetry lies much of this embarrassment with correlating ‘non-nationalism’ to the Villa-Lobos style, with trying to understand his peculiar borrowings of modernist European gestures through the bias of Brazilian modernism. It is worth pointing out that this difficulty is not inconsiderable when somebody tries to define what is ‘national’ in music” (Salles 2013: 685–686).

On the other hand, dances represent an important cultural component in Brazil. In Brazilian folklore, dancing is directly linked with tradition and culture. As an essential element of folklore, it could be understood as a strong expression of a nation and its culture. In particular, research about Brazilian orchestral dances holds great promise. Yet until now a critical study of this repertoire has been minimal. Thus, to investigate Villa-Lobos’ dances should clarify his “musical miscegenation” as his way to building thealma brasileira (Brazilian Soul), i.e. the Brazilian musical language.

An analytical approach based on existential semiotics shows the processes, strategies, and ideology of Villa-Lobos, especially if one explores the mechanics of composition and expression. However, applying this approach to specific Brazilian national or nationalist features – emerging from his particular creative processes – will allow us to identify cultural-musical signs in the Brazilian orchestral music. Thus, this paper aims to portray Villa-Lobos’ gestural writing as the construction of representative elements and meanings through Danças Características Africanas (African Folk Dances), focusing in the first movement of it.

2. African Folk Dances and Brazilian Music Galaxies

Danças Características Africanas was originally written for piano solo between 1914 and 1915, and orchestrated by Villa-Lobos in 1916. This work is one of the first steps of Villa-Lobos to develop his own style. According to Villa-Lobos, melodic material was taken from a community of Africans and Indians – Índios Caripunas from Mato Grosso, the west-central region of Brazil.

This piece has three movements. They are nominated as 1) Farrapós, subtitled as Indigenous Dance no.1 – Young People’s Dance; 2) Kankukus, subtitled as Indigenous Dance no. 2 – Elder’s Dance; and 3) Kankikis, subtitled as Indigenous Dance No.3 – Children’s Dance.

The piece was first performed at the Semana de Arte Moderna (The Modern Art Week) in 1922. That international event held in São Paulo was extremely relevant in outlining Brazilian language of modernism, which included literature, plastic arts, lectures, music, and poems. Villa-Lobos has used an octet version of that music. Despite contrary criticism, African Folk Dances has had an impact because of hybridism and non-conventional language. With no doubt, African Folk Dances marks the beginning of Villa-Lobos’ disruption with the “conventional” style in the sense that it develops his own creative style.

As it is well known, Brazilian music is based in three distinct influences; African, European, and Native Indigenous. First of all, we must consider those influences, through an imagery dimension of three distinct galaxies. This viewpoint by Paulo Costa Lima (2011) gives us a wide and deep perspective of this “kaleidoscope of matches and mismatches, small and big bump” (Lima 2011: n.p.). The “fusion” process was not established in order to melt one in another, but in the way to administer tensions among them in the same space, i.e. universe. So, “the gradual emergence of something different, perhaps a kind of synthesis that the discourse on national attempts systematically to capture from the 19th century” (Lima 2011: n.p.).

In addition, this tension administration involves a power relationship. Considering the “cultural power” of European colonizer, the competition for space (and symbolic forces) puts the other two galaxies at a disadvantage. The European galaxy had the power – the enslavement of black people and elimination of indigenous societies. On the other hand, we should consider that these “gravitational pull” happened on Brazilian universe. Considering that the African cultural presence has made Brazil as a society, or in other words, it was developed in the Brazilian universe, African cultural presence cannot be considered something external, but an important element in the rise of Brazilian culture.

Thus, despite the colonizing power, all attempts of representations will bump to the African galaxy. At the same time we have a paradox; the desire of the colonized in being like the colonizer. This otherness negation is a (probably necessary) paradox in the construction of a collective ethic; based on the combined overview of all interests.

However, to understand African Folk Dances in this context and the framework demonstrated above gives us a different, wide, and deep perception of the distinct elements approached by Villa-Lobos, which we will discuss later.

3. Musical Gesture

Studies around musical gesture have grown during the last decades and issues involving it are not new. There are many approaches to musical gesture (Lidov 1987; Hatten 2004; Souza 2004, 2009; Gritten 2006; Iazzetta 2007; Kühl 2011; Zbikowski 2011) and, no matter the context, there is no formula or closed units to be applied. Research about musical gesture is not systematic, but it is significant to the development of musical signification grammar. In this sense, semiotics applied to musical gesture has been extremely beneficial to draw an analytical tool.

Considering the connection with movement, we should avoid generic associations with physical gestures or tied to a formal function in music, such as opening and closing gestures (Chaplin 1998). On the other hand, gesture is more than movement, “but a movement which can express something” (Iazzetta 1997: 03). Following this viewpoint, we can point out the studies of Zbikowski, Kühl, and Greimas as noteworthy contributions to the approach of this paper.

Zbikowski (2011) has developed his metaphor and music theory of communication-based gesture comparing physical gestures accompanied by speech with the musical grammar. Likewise, Kühl points to “gestalt perception, motor movement and mental imagery” (Kühl 2011: 125). As a result, these approaches place us in a position to understand gesture as a directionality agent. In the music context, gesture is a conductor of the expression of the composer. In other words, in the compositional field, gesture is a strong manipulation attitude, even if we consider temporality, signification, narrative, continuality, and so on. In this way, we can claim that gesture is a means to clarify compositional attitude through musical narrative. It could directly correlate with cultural experience.

On the other hand, Greimas (1987) demonstrates a distinction between natural e cultural elements in a semiotic system through gestural system. His approach points out to gesture as “substance” of body movement. Not so far from the music context, gestural sense lies in the perception of directionality; an idea of intention.

At the same manner that natural gesture – a natural phenomenon, as a motor motion – is based on physical movement; learn, develop, and transmit it is a social-cultural phenomenon. In this sense, the transformation of natural gesture into cultural gesture can provide us different typologies of culture – typology of socialized gesticulation, especially if one wants to explore a specific culture or composer.

According to Greimas, the signification of the word meaning is understood as referencing or direction – referencing as code of expression and code of content, and the latter as intentionality. In his viewpoint, intentionality establishes a relation between “the itinerary covered and its end points” (Greimas 1987: 27). Thus, it could be applied in the music context as well, approaching composer’s intention and compositional thought. Therefore, it is possible to realize gesture as a directional element of intention of composer within his cultural experience, i.e. a temporal construction of directionality.

This temporal construction manipulated through the continuum can be “modalized”. It allows gesture to bear and convey meaning and semantic gesture in modal categories can create a particular sense effects in the musical discourse. These modalities act on the value of object in sense to “affect the modal existence of the subject” (Fiorin 2007: 04). Furthermore, to understand that the value applied to an object/sign is in its representative value and also in its relation to other sign/object could provide a web of connections in a musical work. Those connections, based on the values applied to a sign, offer coherence and directionality to the musical flow.

In this manner, gesture as a sign may be relevant to the structures of production of values. It can be understood as representative values used by composers. Compositional attitude of composer reflects, in this way, representations of socio-cultural experience in discourse. Thus, one can say that representative values seem to be fragmented. Nonetheless, from this strategic manipulation and segmentation of the continuum emerges the notion of intentionality, which increase the significant character of gestural syntagma. On the other hand, based on the modality semiotic concepts, these apparently fragmented ideas are elements of narrative tied to the form of music and production of values.

As production of values, musical gesture can be significant in the process of figuring composer’s identity embedded of ideology and attitudes. In the same manner, the values produced are fundamental in the determination of discourse modalities.

Even considering that gestural units cannot constitute a signifying system, as linguistic system is, what determines the identity of an object is its value and the opposition relation maintained with other objects. Thus, according to Greimas gesture is incorporated into the communication process and transformed into autonomous codes. Therefore, it reacquires mythical contents establishing a “functional organization and narrative, which control the musical discourse, from the music compression as mythical communication” (Souza 2009: 297).

4. Villa-Lobos and Existential Semiotics

Despite the great number of distinct analytical approaches to Villa-Lobos’ works, understand his style, strategies, and compositional process still a challenge. Besides, it is very difficult to portray a wide framework of Villa-Lobos’ work. His musical language is not systematic, but it is probably connected to his expressive impulse, cultural experience and personality.

Considering that music semiotics can embrace a wide range of approaches, existential semiotics opened a new paradigm in the analytical studies of signification and communication. “Semiotics is in flux” (Tarasti 2012: 71), studying the sign in movement and flux gives us new possibilities to understand compositional attitude and process. Knowledge provided by existential semiotics opens new horizons to demonstrate Villa-Lobos' gestural and compositional process/attitude, especially through cultural experience and ideology.

As known, the existential semiotics combines Moi/Soi (individual and collective subjectivities). “It portrays semiosis not only as a movement of the collective Hegelian spirit” (Tarasti 2012: 29), but even musical gesture, energy, process, attitude, ideology, and so on. Following modalities concepts as processual concepts, analyzing Villa-Lobos’ works based on existential semiotics could provide significant tools to understand Villa-Lobos style and process from another viewpoint. In other words, it is possible to reveal some new clues about Villa-Lobos compositional process in the building of the Brazilian soul.

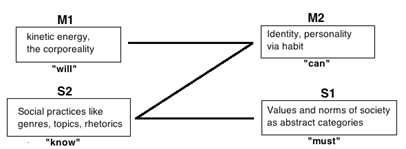

Thus, in the Z-model (figure 1), M1 is primary kinetic energy, the corporeality, desire, body; M2 is identity, personality, habit; S2 is social rules, practices, topics; and S1 is values, norms, general codes.

Fig. 1: Tarasti’s Z-model – Moi/Soi.

Applying it to Villa-Lobos, M1 is his primary corporeal rhythmic and kinetic experience, phenomena, elements, his basic rhythmic entities; M2 is all the primal rhythms and gestures as developed into his personal manners and habits; S2 is genres, topics, and so on, representing the rhythmic social experience in Brazil – in this cases dances; and S1 is Villa-Lobos’ aesthetic – rhythm as one of the basic elements, slow-fast, and so on.

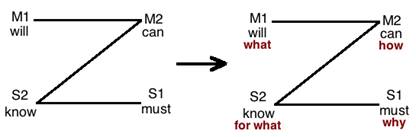

With regard to disclose the compositional attitude/process, a compositional theory probably is a good way to that. Lima (2011b) has investigated Lindembergue Cardoso's[1] (1939–1989) work and pointed out to the articulation of a compositional theory through his composition teaching process. Based on Cardoso's notes, Lima shows four points of his compositional practice: “compose what”; “with what”; “for what”; and “why?”. According to Cardoso, that process is in order to place students to face their choices. This theory (process) exemplifies the composing ways (“with what”) based on creative process (“what”), dimension (“for what”), and indefinitions/answers (“why”) (Lima 2011b). Crossing this theory and existential semiotics should provide tools and means to demonstrate compositional attitude, gestural, and process (figure 2).

Fig. 2: Z-model and compositional theory.

Considering the simultaneity of events in music (sound), communication between Moi and Soi happens in different dimensions and directions. Through the theoretical framework demonstrated above, this intersection (IS) (figure 3) should be understood, in this case, as Villa-Lobos’ compositional ideology. In other words, horizontal and vertical aspects of music, divided in distinct layers and dimensions, could be evidenced in order to reveal some aspects of Villa-Lobos compositional process.

Fig. 3: Moi-Soi – communication/intersection.

5. Analyzing

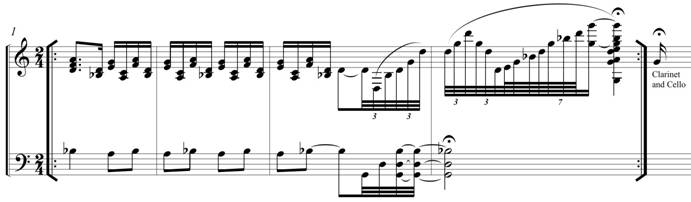

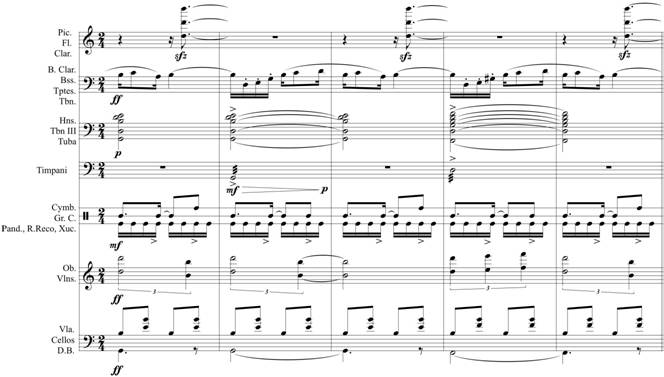

A very expressive gesture is presented in the opening of this piece (example 1). This textural gesture carries a communicative and semantic load through the range of the orchestra. It was articulated in order to keep enough energy in this short time. The energy accumulated is directed to reinforce the beginning of the theme. It provides a powerful communication and semantic load through manipulation of continuum. This gesture illustrates Villa-Lobos’ compositional strategy (attitude) – directionality and expression. An idea of directionality and intension is very clear, reinforcing the beginning of theme – since theme stars with just one note. In a linguistic-narrative way it could be seen as a pointing gesture. Villa-Lobos is intentionally pointing and directing to reinforce the theme through this textural gesture. Thus, Villa-Lobos’ gestural attitude is strongly communicative and expressive – personal style.

Example 1: African Folk Dances, 1st Mov. mm. 01–09.

A quick check throughout the score of African Folk Dances, the first thing one can notice is the rhythm. The emphatic rhythm, and strategies of repetitions evoke the communality sense to this piece. The principle of communality, strategies of repetitions, and construction of temporality are reflected on the careful treatment of the emphatic rhythm. One can say music is “time architectures”, and acttualy it is (Lima 2011a). Villa-Lobos used it perfectly, approaching the rhythm in a widely way more than simply beats or patterns, covering the whole of music – constructions of temporality.

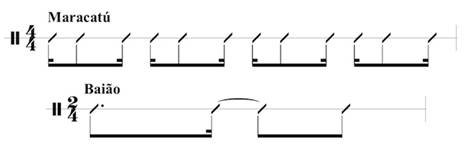

Example 2 shows African-rooted rhythms present in this music. They carry influences of Brazilian popular music – maracatú and baião. It reflects Villa-Lobos personal experience and identity.

Example 2: Rhythms: Maracatú and baião.

Thus, an african-based rhythmic construction keeps traces of communality, especially through strategic repetitions. Moi 1, the kinetic, the corporeality is embodied by those rhythmic strategies. This supposedly rhythmic symmetry reflects the representative communality tied to Villa-Lobos identity and personality (Moi 2). The “primal rhythms” and gestures are developed into his personal manners and experiences. The strategy of repetition adopted by Villa-Lobos could be quite predictable, but on the other hand it keeps the communality and sometimes it contrasts with harmony. This compositional attitude is demonstrated by example 3. This gesture is a clear demonstration of Villa-Lobos’ intention of using rhythmic repetition as compositional strategy in the construction of his discourse. Villa-Lobos is using his personal experience to denote the African environment and communality in this music. At the same time it sounds very Brazilian.

Example 3: African Folk Dances, 1st Mov. mm. 25–28.

Social experience of Villa-Lobos (Soi2) is represented by this “popular influence” and in the superposition of different layers of rhythms and gestures. It results a rich Brazilian rhythm with African influence in the main plan.

This rhetorical representation is evidenced in example 4. The melodic material (2nd staff) is reaffirmed by repletion. Baião rhythmic figure is in the percussion section. The triple figure, in this context (3 against 4 or 2), expresses the African genre and topic into this music. Nonetheless, this figure is not in the piano score, this insertion of “new material” suggests that Villa-Lobos’ compositional attitude was intentionally influenced by his social experience. The values represented are tied to the musical narrative and Villa-Lobos’ social and cultural experience. The elements of musical gesture are significant in the compositional process embedded of his ideology and attitude. Thus, the mythical load works to organize the narrative and establish a communicative musical discourse.

At the same time, the representation of the indigenous is demonstrated by apparent simplicity of thematic material (primitive aspects). Villa-Lobos strategically uses the indigenous element represented by “primitive aspects/elements”. Taking into account the Brazilian mix culture (galaxies), example 4 is a good demonstration of the balance among those “galaxies”. This representation is strongly supported by Villa-Lobos’ social-cultural and personal experience (Moi2-Soi2) and conducted by his personal style (Soi1).

One significant aspect to be considered is the representation through different layers. It is a good demonstration of intersection of Moi-Soi. It indicates Villa-Lobos’ intentional discourse in the sense of balancing those “gravitational pulls” among the galaxies of Brazilian universe.

Example 4: African Folk Dances, 1st Mov. mm. 34–36.

In this blended Moi and Soi, the apparent triumph of Moi has been shown by the seduction of the rhythmic appeal, the emancipation of the rhythm. The rebellion of Moiagainst Soi is controlled breaking tonal expectations and delaying resolutions. Harmony acts dynamically as answer and question. Villa-Lobos uses some modal modifications and especially the whole-tone scale to expand and delay the resolution, breaking the staticity dominant-tonic.

Example 5 shows the whole-tone scale, procrastinating resolution and expanding the tonality. It breaks the “predictability” of the rhythm and the dominant-tonic resolution. This staticity of non-resolution harmony over the communal aspects of the rhythm introduces unpredictable elements into this music.

Example 5: African Folk Dances, 1st Mov. mm. 102–105.

This distinguished texture is relevant to the discourse of this music. The gesture is turning the sign in another communicative direction. It is indexing the communicative and representative energy to lead to other musical material and draw the attention of the listener. The musical gesture is carrying enough energy to communication and meaning.

However, that gesture works in order to balance internal forces through tonal and rhythmic expectation breaking. At the same time, that communicative-narrative gesture highlights the coherence of Villa-Lobos’ compositional and choosing process. The linearity within the continuum leads to the corporeality embodied by those rhythmic strategies. The approximation of subjectivity and objectivity of this gesture narrows the narrative regarding to musical making.

6. Concluding remarks

Understand Villa-Lobos’ style still being a complex endeavor. Thus, “the notion of identity followed by Villa-Lobos would not be an essence to be discovered, but the construction of a sense” (Souza 2010: 196). In this sense, this paper attempted to show, in parallel with the musical grammar, gesture as a compositional strategy; part of the composer store of intonations. In the same manner, faced with different analytical approaches to Villa-Lobos’ work, existential semiotics could be extremely significant to reveal “new points” about his music and style.

Through the theoretical framework demonstrated above, in “the light” of Tarasti’s existential semiotics, it could be possible develop an analytical tool to track Villa-Lobos’ compositional process, attitude, and personal style. Probably, identify a specific style would not be possible, but a unique style in some pieces. In other words, this analytical approach could show some peculiar aesthetic and style of Villa-Lobos in African Folk Dances.

Note

This research is supported by CAPES at Federal University of Bahia and the University of Helsinki.Cleisson Melo is a CAPES scholarship student Proc. BEX 11843/13-6. CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazil, Brasilia – DF 70.040, Brazil.

References

CAPLIN, William E. 1998. Classical Form, A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

DAVID, Debora Leite. 2006. Resenha de Estampas do imaginário: literatura, história e identidade cultural, de Eneida Leal Cunha. http://www.revistas.usp.br/viaatlantica/article/view/50054/54183 (accessed 11 December 2014).

DEBRUN, Michel. 1990. A Identidade Nacional Brasileira. [The Brazilian national identity]. In: Estudos Avançados 4 (8): 39–49.

FIORIN, José L. 2007. Paixões, Afetos, Emoções e Sentimentos [Passions, Affections, Emotions and Feelings]. In: Cadernos de Semiótica Aplicada. V.05 N.02.

GREIMAS, A. J. 1987. On meaning: Selected writings in semiotic theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

GRITTEN, Anthony & Elaine KING. 2006. Music and gesture. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

HATTEN, Robert S. 2004. Interpreting musical gestures, topics, and tropes: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

IAZZETTA, Fernando. 1997. Meaning in music gesture. In: International Association for Semiotic Studies. VI International Congress. Guadalajara, Mexico. http://www2.eca.usp.br/prof/iazzetta/papers/gesture.htm (accessed 26 December 2014).

KÜHL, Ole. 2011. The Semiotic Gesture. In: Anthony Gritten and Elaine King (eds), New Perspectives on Music and Gesture. 123–129. Farnham: Ashgate.

LIDOV, David. 1987. Mind and body in music. In: Semiotica, 66(1/3): 68–97.

LIMA, Paulo C. 2011a. A influência da África nas músicas brasileiras [The African Influence in Brazilian Music]. Retrieved November 11, 2014, from http://terramagazine.terra.com.br/blogdopaulocostalima/blog/2011/10/20/a-influencia-da-africa-nas-musicas-brasileiras/ (accessed 11 December 2014).

LIMA, Paulo C. 2011b. O problema, o sistema e a mão na massa [The problem, the system and hands on]. http://composicaoecultura.com/coloquio/tag/lindembergue-cardoso/(last accessed: 27 December 2014).

SALLES, Paulo de Tarso. 2013. “National Identity, Modernity and Other Intertextual Relations in the Ninth String Quartet of Villa-Lobos”. In Music: function and value. Proceedings of the 11th international congress on musical signification. 27 IX-2 X 2010, Kraków, Poland. p. 684–697.

SOUZA, A. R. 2004. Ação e significação: em busca de uma definição de gesto musical [Action and Signification: toward a musical gesture definition]. São Paulo, SP: Universidade Estadual de São Paulo (UNESP) thesis.

SOUZA, A. R. 2009. Gesto Musical: Ação e Significação [Action and Signitication]. Anais do V SIMCAM. http://www.soniaray.com/simcam/anais_do_simcam.pdf (accessed 27 December 2014).

SOUZA, Rodolfo Coelho. 2010. Hibridismo, Consistência e Processos de Significação na Música Modernista de Villa-Lobos [Hybridity, consistency and signification processes in modernist music of Villa-Lobos]. Ictus 11(2). 151–199. http://www.ictus.ufba.br/index.php/ictus/article/view/217/232 (accessed 28 December 2014).

TARASTI, E. 2000. Existential Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

TARASTI E. 2012. Semiotics of classical music: How Mozart, Brahms and Wagner talk to us. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

VILLA-LOBOS, Heitor. 1929. Danses africaines: danses des indiens métis du Brésil: pour orchestre. Paris: Editions Max Eschig.

[1] Lindembergue Cardoso (1939-1989) was born in Bahia/Brazil. He was one of founders of Grupo de Compositores da Bahia (Bahia Composers Group) – important movement in 1960’s and 1970’s, which was concerned to musical education and disseminates contemporary music. Cardoso composed a great number of music in distinct genres and developed an important approach about teaching composition.