TRANSMEDIA AND SEMIOTICS, A STRUCTURAL MODEL FOR TRANSMEDIA DYNAMICS

Breda University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands

Breda University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands

Abstract

Developments in media have occurred at a fast pace since the beginning of the 21st century and, with these new developments, come new challenges and new ways of entertaining audiences. One of these developments has been transmedia storytelling, a new storytelling technique in which a story world is told across multiple media platforms that all give a unique and valuable contribution in the unfolding and understanding of the story world. Jenkins popularized this term in 2006, and many definitions and developments have arisen in the years subsequent to this. Despite Jenkins’ success, a structural and dynamic model of transmedia seems to be missing; a model that explains how transmedia structurally works and how we motivate audiences to travel across platforms. This paper will demonstrate that by developing such a structural model, which can explain and illustrate the works of a transmedia narrative, the use of semiotics proves to be a relevant approach. The model is derived by examining the associative relations model of Saussure and re-building this to reflect transmedia standards.

1. Introduction

One of the newest terms in media phraseology seems to be one that binds all types of different media together: transmedia. This enticing word by Henry Jenkins (2006a) has made the media industry realize that they can develop a coherent story world and combine different media platforms, where each platform has a unique and valuable contribution, that has a massive impact on different kinds of audiences and provides them with a greater sense of engagement.

However, Jenkins’ explanation of transmedia worlds seems to lack a structural core and it has, therefore, been difficult to clearly define the structure of transmedia. Subsequent theorists have endeavored to follow Jenkins’ definition and to build upon it more and more, but even though this has resulted in very interesting world building and narrative techniques there still is no structural approach. This despite the fact that researchers, such as Long (2007) and Scolari (2009), have attempted to use semiotics in order to find a more structural definition.

Moreover, an increase in the development of transmedia franchises by the industry can be noted. Whereas in the past transmedia franchises used to be developed relatively incidentally, due to the initial platform’s success, they are now created with intent and purpose and are produced from the outset to enable a greater success for the franchise.

The changing landscape in the industry calls for a more structural model that shows how transmedia works and is consumed. Moreover, it could capture the order in which the audience can navigate throughout a transmedia franchise and will eventually portray a meta-narrative. When fully understanding this dynamic system of meta-narratives and transmedia structure, it can be controlled. This paper aims to use semiotics in order to develop a model that demonstrates how transmedia is read and represented in total to the audience. Semiotics offers a broad palette of theories and structures that are able to strip off all excesses of aesthetic abundance and grasp the essential elements that make up the strengths, weaknesses and reading format for transmedia.

Before heading into creating the model there is a need to comprehend transmedia as a narrative technique; looking into a number of narrative theories regarding transmedia and the building blocks as discussed by Jenkins (2006a) and Long (2008) will provide the basics of defining and creating a transmedia world. To put this knowledge into semiotic perspective the basic model of associative relations by Saussure (1972) will be reviewed, however this model from 1972 needs to be rewritten to make it applicable for works in the digital era. We will address and examine multiple theories on the digitalization of semiotics and review old theories and transform them into the current situation of transmedia dynamics

2. Where old and new differ

Audiences have changed from an analogue to a digital group where the need for information seems to be the highest need of all. We have become information hunters and gatherers.

Now extensive opinions are shared about whatever the audience sees in media; every audience member has become a possible critic with their own Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and blogs. They can be positive, but mostly tend to be critical since their opinion can be given as anonymously as they want, we would like to refer to these quick and imminent opinions as an audience siege. Moreover the audience has the possibility to create its own versions of existing content for placement on the web as well as distributing it via media channels like YouTube and Vimeo, better known as fan fiction. Henry Jenkins researched this change in audiences, which he later referred to as theparticipatory culture.

A participatory culture is a culture with relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices. A participatory culture is also one in which members believe their contributions matter, and feel some degree of social connection with one another (at the least they care what other people think about what they have created)(2006b: 7).

In order to comprehend the ways in which transmedia is built up and created, it is important to understand transmedia narratives and their components. There have been multiple definitions of transmedia and all seem to contribute to an important piece of knowledge. Jenkins was the first to define this new storytelling technique. In his bookConvergence Culture he describes that “A transmedia story unfolds across multiple media platforms with each new text making a distinctive and valuable contribution to the whole. In the ideal form of transmedia storytelling, each medium does what it does best.” (2006a: 97–98).

Jenkins’ foremost acknowledgment of a transmedia narrative is twofold and places some preliminary conditions. Firstly there is the usage of multiple platforms, ranging from film and television, to books, comics, games and many more media experiences. Secondly it is important to understand that each media platform needs to contribute to the complete understanding of the storyworld created.

Vital to acknowledge here is that even though each platform consists out of their own distinctive and valuable contribution, they have to be consumable as a single platform and enhanced by the others. This is where it gets complex. How can transmedia developers ensure that each platform enriches the knowledge and experience the audience has when it comes to the story world, but remains consumable on its own nevertheless? Here, Jenkins seems to imply to a meta-narrative, one that gives transmedia developers a firm grip on the entire world.

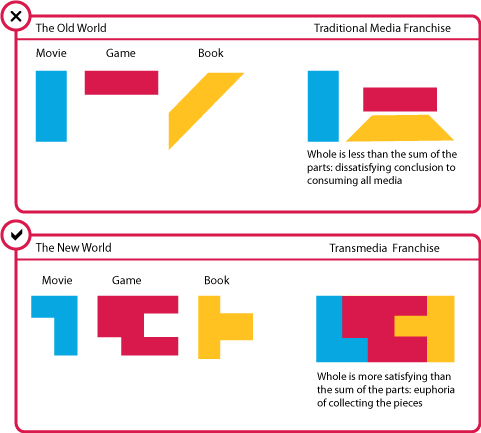

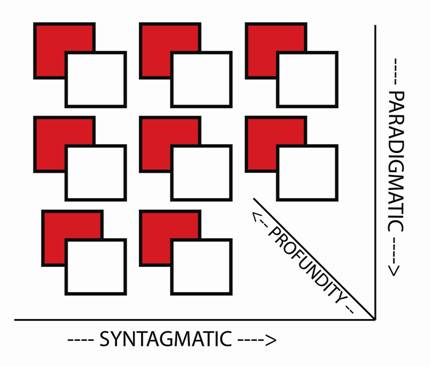

A mistake that is often made is to perceive transmedia as being the same as crossmedia. While the use of different platforms is a broad similarity, there is one vital aspect of transmedia which crossmedia does not possess and the difference between crossmedia and transmedia can be best explained by visualizing both. Robert Pratten has portrayed cross – and transmedia as building blocks and defines them as the old and the new world. As can be seen in figure 1, in the old, crossmedia world all elements combined do not give more a satisfactory whole. In comparison, the new, transmedia, world, sees each element fit right into place to build understanding and comprehension of the entire story world. Each platform, therefore, becomes more interesting to consume because of each platform’s unique contribution to the whole.

Pratten acknowledges one of the key factors of complexity concerning transmedia development, each separate media should be consumable and comprehendible when consumed by itself, but at the same time the sum of all parts, and thus different media platforms, have to consist as a whole, forming the meta narrative. For this he carved out a model to understand transmedia and how it differs from former crossmedia narratives.

Fig. 1: Robert Pratten’s transmedia model.

Besides these two theorists, Long (2007) and Scolari (2009) have examined transmedia and hinted at some possible structural elements that are entailed, with small elements of semiotics they have taken an important step towards finding an exact transmedia structure. Unfortunately they have not offered a complete structural model from which the industry could benefit. Long’s definition of transmedia touches upon semtiotics. Long states in his master thesis: “Transmedia narratives use a combination of Barthesian hermeneutic codes, negative capability and migratory cues to guide audiences across multiple media platforms” (2007: 3).

2.1 Transmedia dynamics

For a transmedia concept to be a success it is of great importance to make use of the negative capability and migratory cues that Long uses in his definition. Long explains negative capability as: “the art of building strategic gaps into a narrative to evoke a delicious sense of 'uncertainty, mystery, or doubt' in the audience” (2007: 53).

It is not so much about creating tension or excitement, but more about the mystery, which in its turn delivers a hunger for more information. It provides the audience with the feeling of power they can fill in the gaps with their own imagination, here it is of great importance to still leave them with enough curiosity to find out more. Because of our growing need for information has made this a perfect storytelling tool.

Migratory cues are a way to create references to places or things that are not mentioned, explained or shown in the story further. By placing these cues a content developer has the opportunity to expand the story world to an enormous extent. Besides that, it gives the option to the audience to further develop the story themselves, via blogs or forums, which they set up. It creates hints in one media form to look for additional content in a different extension. However, what semiotic definition would these migratory cues have in order to provide them a more solid base for this text migration tool? Here the process of semiosis comes in. Atkin (2006) describes Peirce’s semiosis as the process in which read signs, or codes, are translated to produce a meaningful understanding. Important aspects here are, among others, the prior knowledge that the audience has gained. This translation of codes to comprehensible meaning can be strongly related to the consequences of migratory cues, these cues send out specific signals to motivate audiences to travel across platforms by referring to unknown knowledge. When this sign input is given to the audience, the semiosis process cannot translate it into comprehendible knowledge because our memory does not have this information. Therefore the translation leads to either our own interpretation or to suspension of disbelief. On this latter notion, Murray (1997) already stated we are then actually creating belief based on our prior gained knowledge.

Furthermore Long writes that Barthesian hermeneutic codes also are one of the key elements in creating a transmedia world. Roland Barthes, together with other structuralists, has created a classification system, which helps to further define things like migratory cues and negative capability by developing five different codes: hermeneutic, proairetic, semantic, symbolic and cultural.

By using these different codes, it is possible to enhance the relationship the audience has with the story, and because of the improvement of the intertextual connections between the components in transmedia franchises, audiences are more motivated to go from one media platform to another. This relation is set because the codes are relatively similar to the migratory cues, the hermeneutic codes, however, further define the kinds of migratory cues that are used; some of them, like the cultural code, can refer to existing knowledge the audience already has or is able to adapt from simple sources. Its degree of contribution is, therefore, mostly aesthetic and thus, from a semiotic point of view, less interesting. Because this paper tries to create a structural model, using semiotics, the aesthetics are something that will be stripped away in order to understand the complete core of a possible transmedia model.

When telling your story on different platforms you have to motivate the audience to migrate from one platform to another. A transmedia story world needs different elements to be successful in this, by creating the necessary ‘gaps’ in the story which can be filled in by the audiences’ creativity, or by means of another platform it is possible to generate a lust for more. It is essential to make sure audiences are willing to go from one platform to another, even if that platform is not necessarily their favorite. This is due to the fact that all media platforms are combined in one way or another in the context of transmedia storytelling; in order for the audience to comprehend the entire story world they need to discover and experience each platform. The proposed narratology options by Long show that, by these gaps and references, audiences are motivated to discover more of the world. Even though there are multiple media platforms, in which the audience has to make a choice in what text to read first, there is certain linearity in the discovery.

Now that we have analyzed transmedia from a meta perspective to an operational level, and therefore better understand how transmedia works and is built, one of the most interesting questions is if transmedia producers and developers are able to steer the order, or preferred reading, in which the audience reads all different media platforms and thus the discovery of the transmedia world. To answer this question, this paper makes use of semiotic theories to fully comprehend how (digital) media flow and the way in which a line of reading is taken and set, to establish a basis for the building of a structural model, working from the operational level of semiotics to the meta level. Building a comprehensive model that shows in what way transmedia can be used and read when released will provide the ability to answer this question.

3. Associative relations

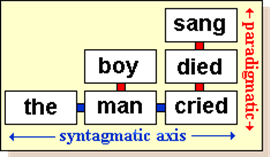

When analyzing signs and texts and their relation to each other, there are two key aspects that are being used, paradigms and syntagms. Ferdinand de Saussure (1972) has built a semiotic model based on these two basic terms, which he later referred to as the associative relations model. When looking into this, perhaps older, form of semiotics we can dissect and amplify the theory to a transmedia scale.

Saussure had a particular interest in the relation between the signifier and the signified: signs versus all other elements of the system, and those between a sign and the elements, which surround it within a concrete signifying instance (Chandler 2007). He described the key differences as being these syntagmatic and paradigmatic forms, and developed a model, that shows the exact implications of these relations and models.

When breaking down these axes to a quite abstract level, we can see that each choice in paradigmatic design has the ability to differ and change meaning according to personal interpretation and preference. Whereas the syntagmatic axis provides this earlier described need for a preferred reading to ensure a logical mental process.

Fig. 2: Saussure’s Associative Relations Model, Chandler (2007: 84).

A paradigm is a term that has come from an elaboration on Saussure’s série associative (‘associative series’), which is a set of signs linked by partial resemblances, either in form or in meaning. Saussure described such sets as being established “in the memory” and the item this associated as forming a mnemonic series (Cobley, 2001: 233). Paradigmatic relations are functional contrasts, since they involve differentiation.

This means that the paradigm is concerned with the selection of this‐or‐this‐or-this (Chandler, 2007: 84). It is about the choice made which media will be consumed at which particular point in time. One of the strong reasons for users to step out of the syntagmatic flow, and step into the paradigmatic axis is to discover more information of the transmedia universe.

When perceiving paradigm as associative it seems the emphasis shifts to sets of signs which relate to one another, again related to the possibilities of substitution in particular positions. When breaking down the term and effect of paradigm it is not merely a set of signs linked by resemblances but it offers the creator and user of the text the ability to change signs and provide his or her own interpretation. This means a text is no longer bound to a set of rules concerning narrative development. It provides a large scale of freedom, as long as the entire text stays in canon. When digging even deeper into paradigms we can see that beyond the point of creating an individual interpretation, the text is coded in such a way that the user or creator of the text offers the possibility to design his own significance within the text. Within this perspective, each choice in paradigmatic design has the ability to differ and change according to personal interpretation.

Syntagms are defined as “a linguistic unit consisting of a set of linguistic forms (phonemes, words, or phrases) that are in a sequential relationship to one another”(Oxford Dictionary 2013). This means a syntagm is always worth more than merely the sum of its parts, it concerns the entire sequence chosen and the (possible) chronology within this string of text. Syntagmatic relations are those into which a linguistic unit enters in virtue of its linear concatenation in a speech chain (Cobley, 2001: 273). It is about the combination of this-andthis-and‐this. (Chandler, 2007: 84) This order creates a clear and understandable linear path and codes the communication in such a way that users experience certain emotions or intuitive paradigmatic choices at carefully placed times. Setting this within the perspective of free choice, it becomes a lot more complicated. Even though the user has the choice to discover every available medium, the producer has to carefully place enough motivational cues for them to migrate to, or click exactly where the producer wants them to.

When amplifying this concept of a string of signs to more than an example with words, it is possible to apply this to transmedia world discovery. In a way, all transmedia platforms are different texts, with each new text making distinctive contribution to the whole. Moreover, all these text contribute to one large meta‐text: the sum of all parts creates a far larger importance than each individually, even though they are created to be sufficient and satisfactory when used as only one text or feature. Another important aspect of syntagms is the (chronological) order. This will provide motivation for the users to travel across features to constantly discover a new (and larger) part of the application. Therefore, the importance of this model lies within the fact that all the elements that make up a sign come from the dynamic and connected or linked illustration of the sign structures by the literature.

But this model has not taken the innovative steps and developments made by technology and media currently into account. Even though this model does seem complete when it comes to producing and understanding meaningful discourse where the signs are words, it does not take the digital revolution into account yet. How do current technological applications, such as databases and transmedia, take this model into consideration? Could they provide a more complete and modern associative relations model?

4. Model contemplation

Saussure’s model does not seem to be fully complete in the context of current technological developments: in this time where we see changing behavior and attitudes towards information processing and usage, we have to take these new innovations into account and re‐apply them to this semiotic model of navigational possibilities. Nowadays, when databases are packed with information and are constantly expanding, there is the possibility of completely rearranging the way we compose texts. There seems to be infinite possibilities for encoding messages, narratives and media but the importance is the actual encoding of those messages by the database, resulting from the given user input, in order to create valuable discourse with the user.

4.1. A database of possibilities

When looking into the understanding of a computer-system’s works when it comes to generating signs and meaning we see that the system is a dynamic machine that makes up the string of signs (code) because of the generated input by the user. This constant importation of information in return generates a complex and tailor‐made code back to the user. But the databases accessed by the dynamic machine are infinite and constantly expanding because of the constant import of (new) information by users. It is then due to this that the options become infinite and the order of signs are no longer fixed; they are completely dependent on the input by the user. The order ceases to be prescribed by writers, directors or other content creators. As an example, this paper is a finite document which is to be read in the order as prescribed, however when accessing a system that has unlimited possibilities of which the output depends on the given input, there is no longer a clear understanding of where text starts or ends cleanly. Especially the works of Aarseth (1997) and his notion on cybertext and ergodic literature apply here. However, our thoughts on his works and those in the perspective of semiotics have already been described in Bouwknegt’s (2011) earlier works. But the importance of a linear, syntagmatic reading remains to ensure a logic and satisfactory understanding, and options and choices are then influenced by the context revolving around them.

When considering our primary associative relations model, we see that all these paradigmatic decisions and choices can be unlimited, but are limited by developers to provide a clear and coherent service or product. The syntagmatic linearity on the other hand is one that has to be used if developers want to ensure a natural and intuitive design and choice process for their users.

4.2. Addition to the model

Where Saussure expresses different kinds of linguistic features, being words, a newer model taking the digital possibilities has been created by Bouwknegt (2011) in his book, Beyond the Simulacrum. He has already highlighted and researched a translation of the initial model to one that is concerned with all possible signs, platforms or even narratives. It is these findings made by Bouwknegt that create a larger understanding of digital media usage and choice.

Here the database of unlimited signs becomes particularly significant once more. Bouwknegt states that the interaction between the user and database is one of the vital aspects when it comes to the usage and understanding of the database. Whenever the user provides the system with input, the system has to encode a specific message. Here it becomes clear that the system relies on the input given by the user and cannot provide meaningful discourse on its own.[1] (2011)

This would mean that even though the media can display all kinds of signs that refer to the state of reality, they could only imply this reality instead of being the reality. In order to become the actual reality, media needs the unlimited resource to all possible signs and codes. By making the user information permanent and apparent, databases and the use of these databases are improved to a higher level in which producers and developers are completely aware of the consumption behavior of the users of media.

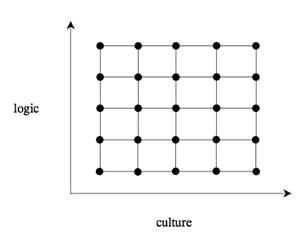

Fig. 3: Network of signs.

The model of Bouwknegt as shown (figure 3) above is one that shows “whether signs are coded logically by algorithms or coded culturally. All respective levels are related and can influence each other” (2011: 122).

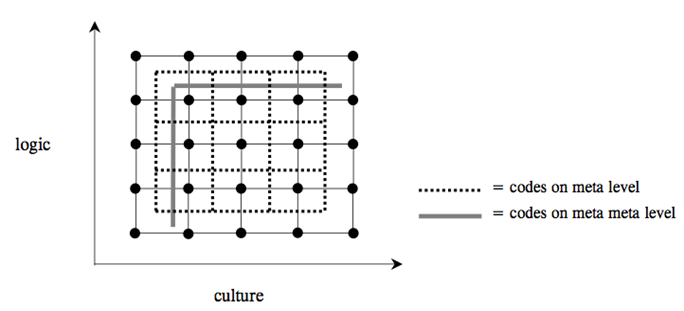

Even though the axes of syntagms and paradigms are replaced with respectively cultural and logic references, we can still view this model as one that could have the same purpose. All individual encoded signs relate to one another in a specific way. The logical, and therefore syntagmatic process is due to the exact and intuitive choices made in paradigmatic options provided to the user. Bouwknegt did see there is an additional level to this already, and how they correlate (figure 4).

Fig. 4: Hierarchy model.

It are these relations and correlations that each individual sign has that contribute partly to the creation of understanding. One could interpret each sign differently, by involving this hierarchy within every sign; the database can exclude those signs with a high risk of misinterpretation by means of mis‐encoding messages. The codes here cease to remain superficial and create another deeper layer of meaning when generating strings of signs.

The discussion of Saussure’s and Bouwknegt’s model of associative relations mentioned before and the paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations could very well use an addition. As seen before, each sign or medium refers to known, associative meanings. But there is more to it; each sign or medium does not only reference to that exact point, at the same time it represents the actual transmedia world and its (flow of) design. This would consequently mean an extra axis could be added to Saussure’s initial model. This would be the profundity axis that stands for the representation of the actual media channel itself and not only reference to associative meanings. The model would then look more like the following.

Fig. 5: Addition to model.

How does this addition to Saussure’s and Bouwknegt’s models work in practice? Every square represents a sign or a transmedia media channel. The desired linear, and thus syntagmatic, discovery is determined by the exact paradigmatic choices made by audiences that are motivated to travel across platforms by means of negative capability and migratory cues. Moreover, each medium and reference already represents a deeper understanding of the world; this would explain the addition of profundity to the model and narrative.

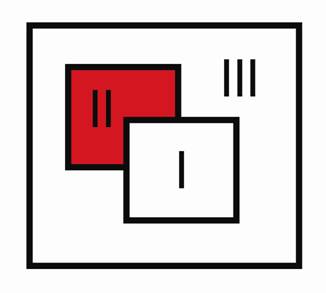

When breaking down this model to one code, it is possible to get a firm grasp on the meta-semiotic design and its relation with developing transmedia (figure 6).

Fig. 6: Meta-semiotic design.

Here, square number I represents the apparent design of a transmedia channel. This means it stands for an actual media type on which a story of the transmedia world is being told. Square number II however, is the underlying code that signifies the migratory cues in such a transmedia franchise. It is the subtle reference to other media types and stories to engage as much people as possible.

Most important here, is square number III, which represents the entire model. This is the meta-semiotic design of the transmedia story, which is the driving force to steer the complete transmedia franchise into a logical syntagmatic sequence. Because of the overarching design, the viewer has enough understanding to make the step for another medium.

With this model, Saussure’s associative relations model has been translated to the digital world of possibilities and transmedia in particular. This model provides transmedia developers with a structural understanding and it captures the way they are able to steer and navigate audiences across different platforms. Moreover does this model show a practical application of transmedia because it portrays the transmedia meta narrative, a dynamic system that by means of the aforementioned tools can be steered in its discovery.

References

AARSETH, E. J. (1997). Cybertext: perspectives on ergodic literature. Johns Hopkins University Press.

BAUDRILLARD, J. (1998). Simulacra and Simulations. Jean Baudrillard. University of Michigan Press

BOUISSAC, P., et al. (1998). Encyclopedia of Semiotics. New York: Oxford University Press.

BOUWKNEGT, H (2011). Beyond the Simulacrum. Münster: Nodus Publikationen. p112–138.

CHANDLER, D. (2007). Semiotics, the basics. New York: Routledge.

COBLEY, P., et al. (2001). Semiotics and Linguistics. New York: Routledge, p233, 273.

FELLUGA, D. Modules on Barthes: On the Five Codes. Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. Purdue U. Available:http://www.purdue.edu/guidetotheory/narratology/modules/barthescodes.html (accessed 27 Feb. 2012).

GEOFFREY, A. Long (2007). Transmedia storytelling: business, aesthetics and production at the Jim Henson Company. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

HALL, S. (1973). Encoding and decoding in the television discourse. Birmingham: Centre for Cultural Studies.

JENKINS, H. (2006a). Convergence culture. New York: NYU Press.

JENKINS, H. (2006b). Fans, bloggers, and gamers: Exploring participatory culture. New York: New York University Press.

JENSEN, F. 1990. Formatering af forskningsfeltet: Computer-Kultur and Computer-Semiotik. In Computer-Kultur- Computer-Medier- Computer-Semiotik, 10–50. Aalborg: Nordisk Sommeruniversitet.

MURRAY, J (1997). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge: The MIT Press. 110.

SAUSSURE, F (1972). Course in General Linguistics. Chicago: Open Court.

SCOLARI, C. A. (2009). Transmedia Storytelling: Implicit Consumers, Narrative Worlds, and Branding in Contemporary Media Production. International Journal of Communication. (3), p586‐606.

PRATTEN, R. (2011). Getting Started with Transmedia Storytelling. n.a.: n.a.

[1] Bouwknegt makes a specific reference to Baudrillard’s simulacrum. Since the simulacrum is not applicable for this thesis, but important to understand Bouwknegt’s findings. The simulacrum that states there is less and less truth, because we base our reality on something that we (mankind) have devised (in film and media) (1998: p166). An example of a 'simulacrum' is that everyone knows how a crashing airplane looks like. But we know this because we have seen this on television. The ‘knowledge’ of this image is not based on our own truth, but the truth is created on TV.