SEMIOTICS OF CULTURAL HERITAGES: THE DIALECTICAL PROCESS OF ASSIMILATION AND REJECTION OF OTHERNESS IN THE CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE AL-ANDALUS CIVILIZATION

Universidade Anhembi Morumbi, São Paulo, Brasil

castromonteiro@anhembimorumbi.edu.br

Abstract

The historic transition from the Arabic-Andalusian to the Christian Iberian Peninsula represented much more than a power shift – or even a religious and cultural transition. It represented also a semiotic catastrophe – borrowing here the famous René Thom’s conception of catastrophe as a small perturbation leading to the disappearance of a stable macroform and giving place to a new one designed by the subsequent balance of structural forces (Poston & Stewart, 1978). In the above-mentioned case of a semiotic catastrophe, the macroform would be conceived as the semiosphere and its inner relations, and the catastrophe as what Iuri Lotman expressed as an overall change in the cultural structures – in this specific situation, passing from a ternary to a binary system. Lotman presents the ternary cultural structure as the one where explosive processes in certain cultural spheres coexist with gradual changes in others, whereas its binary counterpart would be marked by the perception (or misperception) of a thorough destruction of the previous order followed by an apocalyptical appearance of the new one (Lotman, 2004). The present paper aims to illustrate this catastrophe analyzing two opposing constructions of alterity: the Arabic-Andalusian representation of Christians before the Reconquista in the works of authors such as Ibn Al-Haddad (c.1030-c.1087) and al-Rundi (1204-1285) and the Christian representation of the Moors after it in such works as the masterpiece of the Portuguese poet Luís de Camões (c.1524-1580), Oslusíadas. The analyses frontally challenge contemporary mass media stereotypes, displaying a surprisingly modern conception of harmonic coexistence in diversity by the Muslim authors, and an openly biased and manichaeist representation of alterity polarizing Christians against non-Christians in Western writers – with little or no concern at all to the distinctions that separate Muslims from Jews or monotheists from pagan polytheists. A thorough comprehension of this semiotic catastrophe represents a key concept not only to the understanding of Iberian Culture. Its trend to binarism was widely spread both by Spanish and Portuguese Conquistadors, digging deep roots into the soil of the New World. Thus, when Fernando Baez denounces in the title of his famous 2009 book the cultural looting of America (Baez, 2009), the description of the construction of large cathedrals upon the ashes of the once majestic Inca and Aztec temples, pointed by Baez as a token of racist despise for the Native cultures, could be regarded as the mere continuation of a common practice of the Reconquistadors with respect to the formerly imposing Iberian mosques and synagogues. Another interesting phenomenon is the specific way by which Brazil has developed its unique approach to this heritage, combining some ternary aspects that helped it to define its own identity as the friendly “melting pot” defended by authors such as Gilberto Freyre (1933) and Sérgio Buarque de Hollanda (1936) in the beginning of the 20th century with the binary elimination, by persecution and/or oblivion, of most of the huge non-Christian legacy that was deeply rooted not only in its Native American and African populations, but also in its Iberian colonizers.

1. Introduction

The historic transition from the Arabic-Andalusian to the Christian Iberian Peninsula represented much more than a power shift – or even a religious and cultural transition. It represented also a semiotic catastrophe – borrowing here the famous René Thom’s conception of catastrophe (Poston & Stewart, 1978). In this case, it would correspond to what Iuri Lotman designated as an overall change in the cultural structures, passing from what he defined as a ternary to a binary system. Lotman presents the ternary cultural structure as the one where explosive processes in certain cultural spheres coexist with gradual changes in other spheres, whereas its binary counterpart would be marked by the perception (or misperception) of a thorough destruction of the previous order followed by an apocalyptical appearance of the new one (Lotman, 2004). The present paper aims to illustrate this catastrophe analyzing two opposing constructions of otherness: the Arabic-Andalusian representation of Christians before the Reconquista in the works of authors such as Ibn Al-Haddad (c.1030–c.1087) and al-Rundi (1204–1285) and the Christian representation of the Moors after it in an excerpt of the masterpiece of Portuguese poet Luís de Camões (c.1524–1580), Os lusíadas. The analyses frontally challenge contemporary mass media stereotypes displaying a surprisingly modern conception of harmonic coexistence in diversity by the Muslim authors, and an openly biased and often caricatural Manichaean representation of otherness polarizing Christians against non-Christians in Modern Era poetry. A thorough comprehension of this semiotic catastrophe is a key concept whose range is not restricted to the understanding of Iberian Culture, for its structural role was emulated in many different cultural scenarios, and its polarization into binarism was also transposed both by Spanish and Portuguese Conquistadors into their imperial possessions in the New World.

2. Ibn Al-Haddad

The careful reading of the works of Ibn Al-Haddad (c.1030–c.1088) – some of them apparently autobiographic – and possibly also some traditional sources convinced Ibn Fadl al-cUmari (1301–1349) that early in his life Al-Haddad would have departed to a peregrination to Mecca, a journey nonetheless bounded to remain incomplete, apparently due to his real or platonic involvement with a Christian nun in a Copt convent in Asyût, Egypt (al-cUmari, 1924:385 and Guerrero, 1978) – a version disregarded by scholars as Yûsuf Alî Tawîl, who favors the hypothesis of the nun being from Almería, where the poet has worked and lived a great part of his life (Al-Haddad, 1990). According to Ibn Bassâm (d.c.1147/1148), the nun’s name, called Nuwayra [little light] by the poet, would actually be Jamila [the beautiful one], but Al-Haddad would have changed her name to protect her identity (Foulon & du Mesnil, 2009:246) – neither of the two possibilities offering a particularly likely name for a Spanish Christian nun in those days.

Al-Haddad’s lifetime takes place roughly in the period between the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate in 1031 and the first Almoravid invasion in 1086, thus corresponding to the so-called first period of Taifas. Many authors like Emilio Ferrín consider that age “as close to Renaissance as the Tuscany period of city-states” and also “the apogee of Andalusian civilization” (Ferrín, 2009: 403–404). In such an enlighted context, Ibn Al-Haddad provides us an invaluable example of inter-racial relations in the Convivencia era – a time characterized by a relatively peaceful and remarkably productive conviviality between Muslims, Jews and Christians in the Medieval Iberian Peninsula.

This scenario marked by a cosmopolitan, diverse and relatively tolerant society can surprise contemporary eyes with its positive and even passionate representation of otherness, as in the case of the poem عِيْسَاكِ بِحَقَّ عَسَاكِ [Maybe, my beloved, for the grace of your Jesus' truth]. The monorhyme poem with endings in “ki” follows the wafirmeter, (in the first verse, | u – u u – | u – – – ||). The text is full of gorgeous, meaningful alliterations, as appears already in the first hemistich, ‘assaaki bihaqqa ‘iissaaki, aparonomasia relating the fascination the nun exerts upon him (‘assaaki) to her condition as a Christian (‘iissaaki), in a semantic approximation reinforced by the assonance and isorhythmic accent the two expressions share. It is important to emphasize that such resources are not punctual – on the contrary, they are structural as far as many genders of Andalusian poetry are concerned, and their permanence in Spanish and Portuguese written and oral literatures is unfortunately widely overlooked. Nevertheless, we will focus momentarily on the categories of content rather than of expression, leaving further considerations regarding figures of expression to our subsequent discussions about the next two examples.

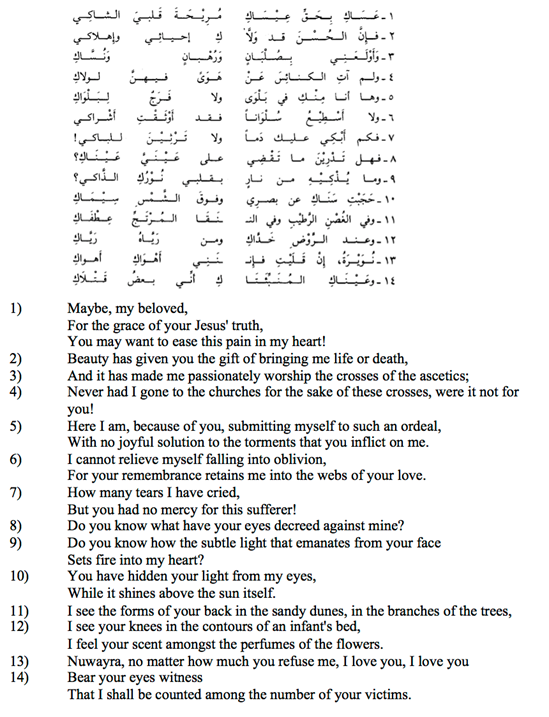

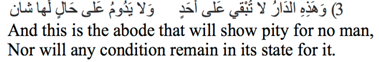

Thus, let us consider the following translation of the above-mentioned poem directly from its original in Arabic (Al-Haddad, 1990):

Fig. 1: Al-Haddad’s original poem and translation.

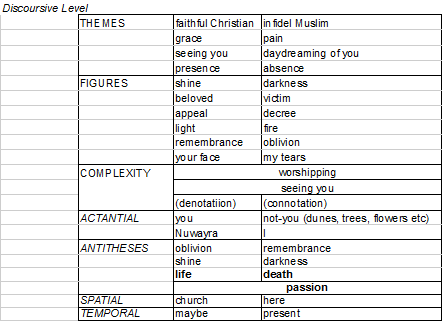

In the discursive level, there is the opposition between the condition of the poet as an infidel Muslim and his beloved one as a faithful Christian. The grace of her presenceis the only possible healing for the pain of her absence, and seeing her an inevitable condition, since not doing so in the denotative meaning implies to be condemned to do so in the connotative meaning by daydreaming of her. He presents himself as a victim of his beloved one – a light that sets him on fire, a shine whose absence throws him into an anguishing darkness. It is useless to try to forget her, for he obsessively remembers her, her beauty imposing itself on him and anything else with the force of a divine decreethat subdues him, while he desperately appeals for her mercy to be loved in return. In his passion, he experiences simultaneously the life that emanates from her and the deaththat her absence means to him. Thereby, the organization of themes, figures and the shifts of time, space and actors result in the following table:

Table 1: Analysis of the discursive level of Al-Haddad’s poem.

In the narrative level, the main opposition is between the realization of the subject when in conjunction with the object of his love and his virtualization when he is in disjunction with her. Thus, her empathic light appears related to states of soul such as love, grace and mercy, whereas the abject fire that burns him in her antipathetic absence is marked by rejection, pain and his obsession for her, thereby allowing the following schematization:

Table 2: Analysis of the narrative level of Al-Haddad’s poem.

Finally, as far as the fundamental level is concerned, it is important to note that the classical opposition between life and death is transcended by what appears in the text as a complex term: passion. Simultaneously a token of life and death, of euphoria and dysphoria, an attraction to which he in vain tries to resist in order to remain a pious Muslim, the intensivity and acceleration that takes the poet towards the infinite extensivity of atemporality, in his passion he finds both the poison and the cure of his divided soul. The organization of that level can be summarized by the following table:

Table 3: Analysis of the fundamental level of Al-Haddad’s poem.

Simple as it may seem, the usage of passion as a complex term between life and death should by no means be overlooked. After all, the fact that the fundamental category of life is convoked in the discursive level to an isotopy of figures and themes related to the imagery of Christendom whereas its counterpart death will correspond to the imagery of Islam implies that passion transcends such a dichotomy, suggesting a semiosphere whose diversity is stable enough to deal with such dualisms without falling into the kind of polarization that is characteristic of Lotman’s binary systems. Hence, the poem seems to express the values of a ternary system where otherness can be presented as a positive value – a feature to be expected in mature and tolerant societies as, in relative terms, the First Taifas era is displayed in most of its contemporaries’ eyes.

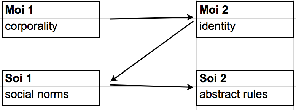

An interesting approach to analyze this phenomenon can be found in Eero Tarasti’s Existential Semiotics. According to Tarasti’s model (Tarasti, 2012), the poet’s corporality (Moi 1), here aroused by his passion for the Christian nun, will become a key ingredient to the restructuration of his sense of identity (Moi 2) – in the present case, triggering a crisis in his self-perception as a Muslim. That crisis puts him in conflict with his previous conceptions of standard social norms (Soi 1), pushing him to redefine them in new abstract rules (Soi 2) whose revolutionary character becomes particularly evident, for the transcendence associated in the text with the poet’s love suggests a social and cultural order where religious barriers have significantly decreased in importance.

Fig. 2: Existential semiotics approach to Al-Haddad’s poem

Thus, the disruptive character of the poet’s passion for the nun can be read as an explosion in Lotmanian terms, taking place here in what the Russian semiotician defined as a ternary structure, for it appears in the semiosphere as a gradual transition to change rather than a radical opening of a horizon of possibilities. In Lotman’s words: “explosion in this case is not characterized by a general catastrophe, for in its inner structure there is a constructive force that cleans the Augias' stalls and opens a path towards a new phase” (apud Gherlone, 2014:65). According to Laura Gherlone, “Lotman calls this dynamics a ‘revolution’, differentiating it from what takes place in binary structures, defined as ‘turbid’ – a situation where transformation is experienced as something confuse, turbulent, irrational” (idem). The gradual transition of the Iberian semiosphere from a ternary to a binary system will be further discussed in the analyses of the following examples.

3. Al-Rundi

In their famous article “Abu 'l-Baqa al-Rundi and his elegy on Muslim Spain”, Ebied and Young attribute to Miguel Casiri the alleged dates for Al-Rundi birth and death (Ebied & Young, 1976:29). Indeed, Casiri, in his classical Bibliotheca arabico-hispana escurialensis published in 1770, states that a poet from Ronda who was the author of De Temporum Cognitione and De Haereditate would have been born in 1204 and died in 1285 (Casiri, 1969:379). Nonetheless, no matter how defensible it would be to identifyDe Temporum Cognitione with a metric treatise attributed to Al-Rundi, the main problem is that Casiri is referring to an author whose name appears in the original in Latin as Ben Shariph Alzabdi – and if the supposition that Ben Shariph and Ibn Sharif can be a same person is more than acceptable, the fact that Alzabdi has no resemblance to anyone of the names associated to Al-Rundi is at least problematic, not to say rather compromising as far as the verisimilitude of that hypothesis is concerned. Anyway, Al-Rundi is the author of a magnificent poem: a lament enumerating the sequential fall of a series od Andalusian cities to the Christian kings in a nuniyya – a classical form of monorhyme poetry with verses ending in nu, culturally perceived in the Arabic semiosphere as an onomatopoeia of crying. The author organizes the melancholic parade of defeated cities in chronologic order with Cordoba as the only exception, for in spite of being the first to fall, it is the penultimate city in the poem – a poetic license justifiable by its status as the former capital of the Caliphate and the importance of its fall to the twilight of the Muslim civilization in the Iberian Peninsula.

Besides an analysis of the plane of content, it is important here to consider once more the structural role of alliterations and their homologations to categories of content as a vital stylistic resource to provide effects of meaning and to enrich the poetic text with varied rhetoric figures. If this procedure was already observed in the first line of the previous example, its systematic usage in Al-Rundi’s لأَنْدَلُس رِثَاءُ – Rithâ’u Al-Ândalus, or Lament for Spain – calls our attention to its outstanding significance in the Andalusian poetry of its time and also to the everlasting influence it would exert in the Iberian literature, far outliving the tragically effective attempts that took place especially between the late 15th and early 17th centuries in order to erase the cultural legacy associated to the Muslim and Jewish heritage that had flourished in the peninsula during the Middle Ages.

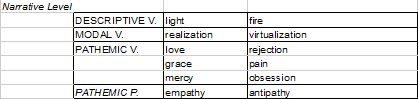

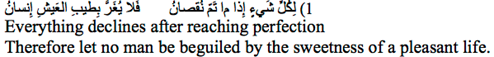

Let us consider the first verse of the original poem (El Gharbi, 2009) and also the brilliant translation provided by James T. Monroe – a reference that we will follow in our comments to all the subsequent verses (Monroe, 1974 pp. 332–334):

Fig. 3: Al-Rundi’s poem, verse 1.

The poem is written in the meter basît, most of the text having each hemistich following the rhythmical pattern:

| u – u – | u u – | – – u – | uu – ||

Both the first and the second hemistichs of the first verse end up sharing words in the same metrical position that present a sequence of phonemes consisting, in this order, of a palatal consonant [n], a sibilants [s/S] and a long vocal [a]. Were such an effect limited to an isolated case of assonance, it would be nothing more than a figure of expression that would enrich the sonority of the text. Nonetheless, there are two very important points to be considered. The first one is that such effects appear so frequently not only in this poem in particular but also in Medieval Andalusian poetry in general that it might be considered as a stylistic coercion valid for a whole set of genres of that period. Not less important, the second point is that the assonances here, constructing homologies with categories of content, establish semi-symbolic relations that, pervading both the planes of expression and content, enrich the poetic text not only in terms of plastic beauty but also in signification. Thus, the sound association between the trisyllabic words ‘nuqSânu’, with its sense of loss and decay, and ‘insânu’, the human being, produces a semantic contagion of the first term ‘decay’ to the second, ‘humanity’, by means of their shared sonority. Thereby, besides the enunciate itself, the rhythmicity in the plane of expression and its homologation with the semantic trace of ‘decay’ will also reinforce the idea of the fragility of the human existence in this world.

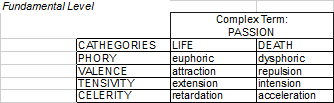

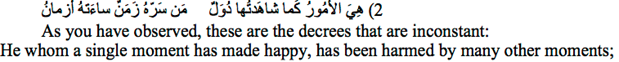

An even more eloquent example of semantic contributions of figures of expression to the process of generation of meaning in the syncretic text appear in the 2ndhemistich of verse 2:

أَ

أَ

Fig. 4: Al-Rundi’s poem, verse 2.

The most exquisite poetic resources here are a consequence of the metrical structure of the verse. The terms زَمَنٌ [zamanun] and أَزمانُ [âzmânu], derived from a same root and related in form and meaning, are both located in the ending of a pair of feet: zamanun – the moment of joy – follows a |u u –| rhythm, whereas the time of suffering, âzmânu, is composed of only long syllables: – | – –||. The consequent effects of meaning are a progressive gradation from a brief state of joy to a long period of suffering, apleonasm and an hyperbole that emphasize the dysphoric character of the comparison lending more weight and duration to the sad rather than the happy moments of life. This effect is also reinforced by the phonetic and rhythmic parallelism between sârahu zamanûn and sâcathu âzmânu, where once more the second pair of words begins with two long syllables whereas the first has a long and a short one.

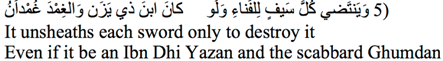

An example of alliteration appears on verse 5:

Fig. 5: Al-Rundi’s poem, verse 5.

In the first hemistich, للفَناء سَيفٍ [saifi alfanâci] – “the sword to destruction” –, in which the letter “f” is associated to the semantic trace of cutting, presents a metonymand/or onomatopoeia representing the sound of the blade quickly moving in the air. Besides, “Saif” is here a double entendre homonymic paronomasia, for it designates also to the first name of Ibn Dhi Yazan, the pre-islamic king of Yemen who became legendary for his power, wealth, faith and bravery and who is quoted in the second hemistich, thus allowing also an interpretation such as “it (fate) disarms all the Saifs (as emblematic heroes) leading them to destruction”. In the following hemistich, some of the main rhetorical tools corresponding to figures of expression exposed so far are reutilized, confirming their structural role in the poem. Thus, غُمْداَنُ وَالغِمْدَ [wa al-ghimda ghumdânu] has in “ghimda ghumdânu” a paronomasia where the three first written letters are identical; a metrical progression from “ghimda” (– u) to “ghumdânu” (–| – –) indicates a dysphoric prolongation analogous to the one described in verse 2, consolidating it as a semi-symbolic relation in the text. The word “ghimd”, that means “scabbard”, is therefore related by form and meaning to Ghumdan, which is the name of the famous and gorgeous palace from where Ibn Yazan ruled Yemen. So, in each hemistich of the 5thverse, a double entendre relation worked as an isotopic connector between a connotation alluding to the imagery of Ibn Yazan’s saga – as an example of the prevalence of fate and the ephemerality of glory –, and a denotation associated with the weapons men stubbornly and hopelessly use to fight for their purposes.

The alliteration of fricatives with the connotation of destruction pervades the poem, as in the aspirated “ه” and “ح” (roughly corresponding to laryngeal and palatal aspirated fricatives) in verse 3:

Fig. 6: Al-Rundi’s poem, verse 3.

Another important resource in the poem, parallelism (in Al-Rundi’s text, particularly the anaphora) marks in that verse the syntagmatic and phonetic constructions lâ tubqî alâ âhadin and lâ yadûmu alâ Hâlin, reinforcing the hopelessness of human condition – a semantic trace that will be extended in the Ubi sunt? sequence in verses 6 to 9, and that possesses in the Arabic term “Ain” [Where] that starts each one of its sentences the suggestive sonority of a lamentation.

As an exhaustive and detailed analysis of the figures of expression and semi-symbolic relations in the 42 verses of Al-Rundi’s poem lies beyond the objectives of the present article, let us advance now to a more general discussion about the generative path in his Lament for Spain:

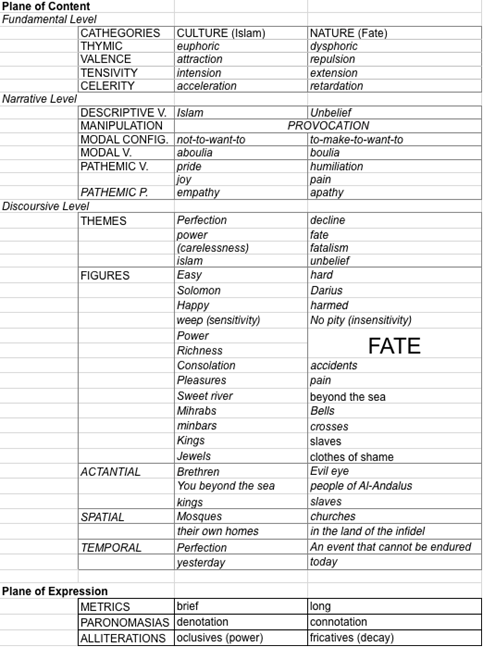

Table 4: Al-Rundi’s poem: generative path.

The thematic opposition between an implacable divine fate and the illusions of power men have nurtured throughout history convoke to the discursive level the main fundamental dichotomy nature x culture. The isotopies related to the careless and self-confident Muslim who believed to have mastered the world to perfection give place to thefatalist observer that can do nothing but witness the victory of the infidels over a decaying Islamic empire. Thus, the figures of a happy, easy and pleasant life ruled with wisdom by people like the king Solomon are replaced by a harmful existence full of hardness and pain, where the tragic fall of once powerful and ambitious tyrants like Dario,Chosroes or Shaddad are copiously enumerated. Bells ring where once there were mirhabs; crosses are raised over the ruins of the old minibars; kings are converted to slaves, and instead of their jewels, they are now covered with the clothes of shame. A temporal shifting out establishes the contraposition of a glorious past to a miserable present, whereas its spatial counterpart opposes mosques to churches, and the homes of the faithful to the wasted land of the infidel and the actantial shifting out establishes brethren ofkings whose members are addressed as “You, beyond the see” as the enunciatees of a discourse that depicts enuncively the people of Al-Andalus converted into slaves under the severe judging eye of an unappealable fate. The narrative level is marked by a complex program of provocation in which the addressee is confronted with the humiliation and defeat of Iberian Islam and challenged in his apathy to remain indifferent to violence and injustice or to take arms in succour to his brethren against the barbarism of the invading infidels. So, the addresser performs a manipulation by provocation imposing a modal configuration of to-make-to-want-to on an initially aboulic – not-to-want-to –, proud and hedonistic addressee. The manipulation, managing as a provocation the negative values of the system, converts the thymic category of dysphoria and the repulsion valence, as the positive values associated to pleasure, pride and power correspond to the conversion of the category of euphoria and the attraction valence. Less evident and more complex are the tensive and celerity configurations that organize the fundamental level, by which the extensiveness of the sempiternal and irrevocable decrees of fate belong to the Nature semantic axis whereas the vertiginous acceleration of the fall of Islamic Iberia and the intensiveness of its joy and suffering follow the Culture axis.

Finally, the main femes that organize the categories of expression in their homologies with the categories of content will equally correspond to the oppositions that organize the fundamental level. Hence, extensiveness and dysphoria will often appear associated with the metric prolongations previously described in this item, and the alliterations can be organized opposing the extensiveness of the fricatives associated with connotations of destruction and decay with the intensiveness of the occlusives that reinforce the imagery of power and pride. Finally, a far more sophisticated resource appears ruling the frequent usage of the paronomasias in the poem, opposing theirdenotative attributes related to the imagery of culture and human pride to their connotative qualities associated to a fatalist point of view deeply rooted in the Islamic conception of the philosophical nature of the universe. The Andalusian philosopher and polymath Averroes (1126–1198) – a giant who left an indelible mark in the history of philosophy and whose legacy, rejected in most of the Islamic world in the first centuries after his death, is essentially inseparable from the ascension of rationalism in Western civilization – writes in his On the harmony of religions and philosophy that a metaphorical approach to the interpretation of the scriptures and the creation (by means of science and reflection) is a privilege of those whose destiny is a further comprehension of reality, whereas a more literal interpretation is proper to those deprived of deeper intellectual ambitions (Averroes, 2012). Hence, Averroes states that those able to this connotative approach would be closer to the nature of truth – a point of view popular enough in the Al-Andalus civilization of Al-Rundi’s time to contaminate his poem and organize in a systemic way his rich and abundant usage of paronomasias in his Lament for Spain.

4. Final considerations

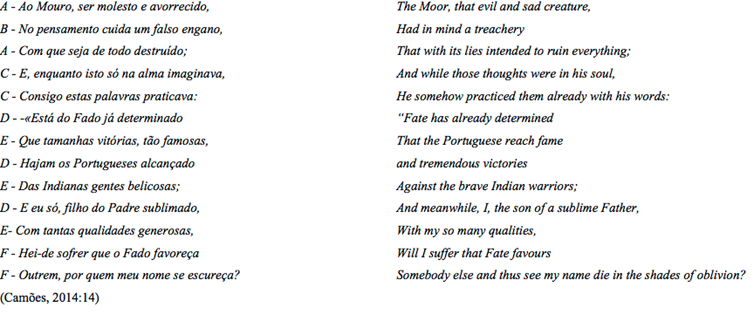

The gradual change in the cultural representations of otherness from the idyllic and passionate admiration for the Christian nun in Al-Haddad’s poem to the somewhat distant and impersonal antagonism with respect to the figure of the infidel depicted in Al-Rundi’s Lament for Spain – more the cold executer of Allah’s will than an enemy to be hated – continues its evolution throughout the centuries until reaching in the early 16th century to the kind of polarization described by Lotman in his definition of a binary system. The Reconquista led not only to the territorial conquest of the Iberian Peninsula by the Spanish and Portuguese Christian kingdoms: between 1492 and 1614, virtually all the Jews and Muslims of the Peninsula were forced either to conversion or to exile and tenths of thousands of books written in Arabic and/or Hebrew were burned (Amelang, 2011) in a general effort to annihilate any traces of what had for almost eight hundred years been the most advanced civilization in Europe and the Western hemisphere (Vernet, 2006). Unsurprisingly, the cultural representations of otherness in both the Iberian and the Muslim world would be deeply affected by this fierce antagonism, as can be seen in this excerpt of Portuguese writer Luiz de Camões’s opus magnus, the gorgeous poem Os Lusíadas [The Lusitanians]:

Fig. 7: Excerpt of the first chant of Camões’s Os lusíadas.

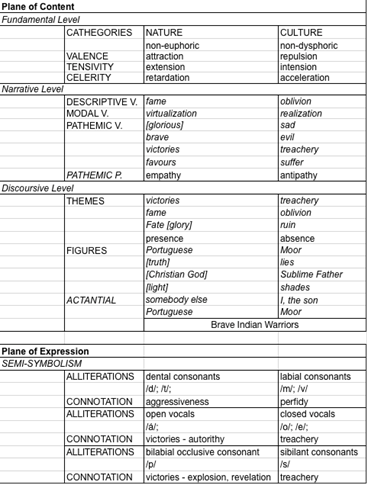

A detailed analysis of the poem similar to the previous discussions in this article reveals a series of alliterations that, as in the former examples, establish important homologies with the opposing semantic axes that pervade the text from the fundamental to the discursive level – and, as seen before, respond also at least partially to the organization of the figures of expression. An analysis of the generative path and symbolic relations in the text is summarized in the following table:

Table 5: Camões’s poem: generative path.

Here, the demonization of the moor, presented as an abject character that subsumes the negative values of the system, will paradoxically mobilize most of the poetic resources we have examined so far. The structural utilization of rhyme – unknown in Western tradition until its popularization in Muslim Spain as part of the Arabian cultural heritage since the 8th century –, an accentual configuration close and stable enough to allow an approximation with a metric structure like |u – | u – | u – | u u u | – – || (3 imbs, 1 tribrach and 1 spondee) pervading the whole poem and the systematic usage of semantized alliterations reveal that this Portuguese text, no matter its explicit islamophobia, paradoxically – and rather schizophrenically – honors the heritage of the many centuries in which the Arabian language and its literary genders dictated the patterns of poetical excellence in the Peninsula. The sibilant consonants and closed vowels, like a serpent hidden in the shadows, represent the perfidious Moor in opposition to the explosive consonants and open vowels that depict the openness, bravery and frankness – by the way, a virtue culturally associated in the West to the Germanic Franks, champions of Christendom – of the Portuguese heroes. Brazilian cultivated and popular literary genders – the last still widely practiced today – would emulate for centuries both the polarization and the formal procedures of the poem above. With a massive presence of New-Christians (descendants of former Jewish and Muslim families) among its first colonizers and too far from the metropolis to be reached by the persecutory arms of Inquisition, Brazil, as other nations of the New World, has preserved some traces of the Al-Andalus legacy in its national ethos and cultural forms of expression. The receptivity to ethnic and cultural diversity and the immediate assimilation of foreigners in a mixed society that was defined by scholars like Gilberto Freyre and Sérgio Buarque de Hollanda as a friendly “melting pot” would according to these authors be part of the Al-Andalus heritage inherited by the Brazilian civilization (Freyre, 1971, 1992; Buarque, 1995) – as the binary elimination, by persecution and/or oblivion, of most of the huge non-Christian legacy that was deeply rooted not only in its Native American and African populations but also in its Iberian colonizers would reflect the proud 16th century obscurantism that would in a few centuries take Portugal and Spain from the position of the most powerful transoceanic empires of their time to the condition of peripheral actors in the geopolitical scene.

References

AL-HADDAD, Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Ibn. 1990. Ed. Yûsuf Alî Tawîl. Diwan Ibn Al-Haddad al Andalusi [Collection of Poems by Ibn Al-Haddad, the Andalusian]. Bayrut: Dar al-Kutub al-'Ilmiyah.

AL-UMARI, Ibn Fadl. 1924. Masâlik al-absar fi mamâlik al-amsâr [A view on the kingdoms of the area]. Cairo: s.n.

AMELANG, James S. 2011. Historias paralelas: judeoconversos y moriscos en la España moderna. Madrid: Akal.

AVERROES, 2012. On the harmony of religion and philosophy. Oxford: Oxbow books.

BUARQUE DE HOLLANDA, Sérgio. 1995. Raízes do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

CASIRI, Miguel. 1969. Bibliotheca Arabico-Hispana Escurialensis. Reproduction of 1760–1770 ed. Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag.

EBIED, R. Y. & YOUNG, M. J. L. 1976. “Abu ‘l-Baqa al-Rundi and his elegy on Muslim Spain”. In: The Muslim World, vol. LXVI, No. 1, pp. 29–34.

FERRÍN, Emilio González. 2009. Historia General de Al Ándalus. Córdoba: Almuzara.

FOULON, Brigitte & DU MESNIL, Emmanuelle Tixier. 2009. Al-Andalous: anthologie. Paris: Flammarion.

FREYRE, Gilberto. 1992. Casa-grande e senzala. Rio de Janeiro: Record.

FREYRE, Gilberto. 1971. Novo mundo nos trópicos. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.

GUERRERO, Amelina Ramón. 1978. “Poesia amorosa de Ibn Al-Haddad”. In: Miscelánea de estudios Árabes y Hebraicos vol. 27, 1 p. 197–204.

GHERLONE, Laura (2014). Dopo la semiosfera: con saggi inediti de Jurij M. Lotman, Milano: Mimesis.

LOTMAN, Yuri M. 2004. L’explosion et la culture. Limoges: PULIM.

MONROE, James T. 1974. Hispano-Arabic Poetry: A student anthology. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp 332-334.

ONTALVA, J. Santiago Palacios. 2014. Al-Andalus tras la caída del califato. Madrid: Liceus,

POSTON, Tim & STEWART, Ian. 1978. Catastrophe Theory and Its Applications. Dover: Dover Publications.

TARASTI, Eero. 2000. Existential semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

TARASTI, Eero. 2012. Semiotics of Classical Music. How Mozart, Brahms and Wagner Talk to Us. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter.

VERNEt, Juan. 2006. Lo que Europa debe al Islam de España. Barcelona: Acantilado.