CULTURAL SEMIOTICS AS FLUXORUM SCIENTIA

University of Turin, Italy

Abstract:

The article is a caveat vis-à-vis the typological excesses of cultural semiotics. Structuralism naturally inclines toward the formulation of grids where cultural artifacts are recognized as tokens of types. Nevertheless, the article argues, such methodological attitude is not ideologically neutral. Pushed to the extreme, it risks overlapping with a politics of rigid articulation of humanity that 20th-century totalitarianisms tragically embraced. The antidote would be to pursue a paradoxical effort of cultivating cultural semiotics as “fluxorum scientia”, as science of fluid, iridescent phenomena.

An urge of attribution pervades semiotics. Peirce has imagined the sign as a triadic structure, Saussure as a dyadic one, but no semiotics could rest on a monistic ontology. Every model of sign is permeated by the idea of a cleft, and by the narrative of a quest to bridge it. In Saussure, the sign is unity of signifier and signified, but this unity concerns the phenomenology of signification more than the ontology of meaning. “Sign” could be defined as the name of everything that humans do in order to bridge the perceptible and the imperceptible, the known and the unknown, the uncanny and the familiar. Interpreting signs is tantamount to transforming a chaotic, puzzling reality into language that speaks and is understood. From this point of view, signification is pervasive, and the scope of semiotics as vast as that of humanity, for living is, for humans, appropriating the unknown. Theories about the genesis of the human semiotic ability often relate it to the needs of hunting, and deciphering the unfamiliar traces left by preys or predators. Increasingly sophisticated languages have been created since the prehistory of humanity, yet it can be argued that the semiotic instinct still is about hunting and being hunted, about turning an unfamiliar environment into a matrix of decipherable elements.

One of the fundamental questions of semiotics, since its inception as semeiotics in the medical field, concerns whether the reading of reality can be guided by technique; whether the terrifying but thrilling experience of turning the unknown into the familiar must be invented at every step through instinct and intuition, or whether, on the opposite, such process of appropriation can be formalized, perfected, taught, and learned. Perfecting interpretation is indeed crucial in all walks of human life, and attribution one of its key processes. Medical diagnosis needs to bridge the gap between some awkward and painful manifestations of the body and the identification of a disease that provokes those symptoms and must be cured to eliminate them. Jurisprudence seeks to attribute a certain human act to a category of behaviors, and relate this to a code or law that rules its existence in society. The reader of a poem or the viewer of a painting must refer the apparently unique arrangement of words and pigments to a genre, a style, a historical and cultural context, and to the poetics of an artist in a certain phase of its evolution. Also everyday life cannot be lead without a modicum of connoisseurship, whose mastery is among the most desirable social skills. Referring fellow human beings to a precise social, cultural, and psychological characterization; ascribing their words and acts to specific categories of intentions; detecting honesty and lie: all these abilities partake in the semiotic hunting that marks the role of humans in both nature and culture.

Being unable of reading the signs of reality, and reality as a sign, means being unable to predict what reality still is not, but might be in the future. That is the case not only for the future of social reality, but also for the future of texts. On the one hand, Wall Street brokers require semiotic ability in order to forecast the course of stock exchange titles. The fact that this ability is not completely formalized as technique does not mean that it stems entirely from mysterious intuition. On the other hand, literary critiques speculating on the interpretation of a novel also debate about the future. In the structural credo, for instance, they argue that the semantic fabric of the novel will elicit a certain range of responses by its potential future readers.

Since antiquity, semiotic theories and techniques have been thought as a remedy to the uncertainty of the future. From this point of view, the place of the semiotic instinct in the evolution of the human species is that of an adaptive quality: those who better relate the current phenomenology of reality to its future developments will be able to react to them in a quicker and more appropriate way. History is replete with anecdotes of humans who failed because, as Americans say, did not see it coming. “See it coming” requires, on the contrary, semiotic skills: see a financial crisis coming, or the end of a relationship, or a new tendency in consumption.

Semiotics as a discipline has therefore faced a double task: on the one side, describing the human consubstantial tendency to decipher the unknown; on the other side, suggesting techniques in order to perfect such innate interpretive drive.

What were the main suggestions of semiotics thus far?

In the frame of Saussure’s semiotics, attribution of an unknown signifier to a known signified requires familiarity with the law. It is the law that associates a red flag to a signal of danger, the lexeme “dog” to a zoological species, burning incense with a propitiatory liturgy. The titanic efforts of Saussure’s followers, from Hjelmslev’s glossematics to Greimas’s generative semiotics, have aimed at grasping the essential law beyond every form of signification. Also those signification processes that seemed patterned by unwritten laws or idiosyncrasy, such as social phenomena or artworks, have been investigated in search of a rule of attribution: given an apparently random configuration of plastic elements, or social behaviors, the application of the semiotic method ascribe them to a law, turn them into the token of a type, interpret them. In this framework, what does not mean simply has no meaning, the unfamiliar is doomed to remain such, and ignorance of the signified beyond a signifier is only temporary, destined to vanish as soon as the suitable code will be detected, known, and applied. That explains why the structural mindset never focuses on how laws are instituted, evolve, or decay: what occupies the core of the semiological project stemming from Saussure’s definition of sign is the law caught at the peak of its development, the human ability to bridge the unfamiliar and the familiar as it is crystallized in a code, in a system, in the langue. That is also why the structural attribution has an exclusively deductive allure: given a rule, a token must be attributed to a type with no exception, and all the cleverness of the semiologist consists in coming up with the most comprehensive formulation of this rule.

That does not mean, though, that the structuralist attribution does not produce any new knowledge. On the contrary, structural semioticians serve the purpose of identifying what explicit code links a token with a type, but also that of eliciting an implicit code from tokens that seem unrelated to any type. On the one hand, the structural semiotician determines that an ostrich egg in a canvas by Piero della Francesca must be related to the meaning of that egg in the coeval heraldic code. On the other hand, the structural semiotician elicits the rule according to which Mondrian’s abstract paintings have been created and prompt aesthetic answers.

Lotman’s model of cultural interpretation is in line with Saussure’s strategy of attribution. Each element in the semiosphere, be it an isolated sign, a text, or a whole language, signifies insofar as it stems from an underlying matrix determining its value in social exchange. Elements in the semiosphere that are not related to any modeling system are chaotic, perturbations coming from outside the semiosphere, or appear as such simply because no semiotician yet has found any suitable way to situate them in relation to the cultural text, in relation with the general pattern of the semiosphere. In Lotman’s model too, the aim of the semiotician is twofold: on the one hand, mastering the cultural and sub-cultural codes that explicitly shape communication in society. On the other hand, inductively more than deductively, establishing how different, apparently random signs are indeed a byproduct of some general dynamics of the semiosphere. For instance, the cultural semiotician will be able to differentiate among different kinds of tattoos, and determine which are to be ascribed to the subculture of detainees in a certain country, which are imported from an ethnic, pre-industrial visual culture, and which are a combination of both. At the same time, the cultural semiotician will seek to put forward more encompassing hypotheses about the spreading of tattoos in present-day societies, by claiming, for example, that the fashionable permanence of tattoos, piercing, and scarification is a reaction to the sense of precariousness that anguishes youth in contemporary western countries.

An important question to be raised about Lotman’s model and about cultural semiotics in general is the question of creativity and innovation. As it was argued earlier,Saussure’s semiology is not primarily concerned with creativity because it is not primarily concerned with time. Semiology provides a structural photograph of the laws that, at a given moment in the evolution of language, underpin the relation between tokens and types. How these laws are created and how they evolve in history concern semiology only retrospectively, for instance when the structural laws of 17-century poetics must be retrieved in order to explain the creation of Shakespeare’s sonnets. However, as regards their interpretation, what matters is not to somehow reconstruct the aesthetic reception of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, but to understand through which codes the analyst’s contemporaries read the sonnets. From this point of view, Saussure’s semiology is always contemporary. Historical semiotics is possible, but has been rarely chosen as a field of investigation, for the epistemology of semiology is more apt at describing the langue of a sign system as static deposit of forms than at speculating on how it might have changed through history.

A giant leap is taken, though, when the structuralist epistemology is applied not to a specific system of signs, like in Saussure, or to a text, like in Greimas’s structuralist semantics, but to culture as a whole, considered as system of signs. It is reasonable, indeed, to crystalize the evolution of scripts for the blind – one of the examples given by Saussure in explaining the scope of semiology as he first defined it – into synchronic still frames, since such evolution can be ascribed to a context, for instance, the changing place of sensory impairment in modern societies. The same goes for Greimas’s analysis of Bernanos’s works in Structural Semantics: here too, there was no need to place the French novelist’s texts in the flux of time, like historicist criticism would do, for in this case too such evolution would be relegated in the context. In Lotman’s semiotics, though, and more generally in cultural semiotics, there is no context. What is the context of a culture, indeed, if not another culture, that is, something that is external and relatively unrelated to it?

As a consequence, in cultural semiotics there is no creativity that is not somehow combinatorial, stemming from the rearrangement of existent types according to different rules rather than from the unfathomable creation of new types. Lotman’s semiotics accounts for innovation also through contamination between or among semiospheres. However,like abduction in Peirce, contamination in Lotman is magically referred to more than explained. The issues of how precisely inter-cultural contamination would work, and of how it would generate change in the semiosphere, are left unaccounted for. That ultimately derives from the circumscribed character of the structuralist epistemology. In order to work as an explanatory model, a cultural structure must be closed, its topology determined by precise frontiers. Also Saussure’s langue is a closed system, as it is closed the system of Greimas’s text. However, considering a whole culture as a closed system brings about a vision of society that implies disquieting secondary effects.

In other words, the urge for attribution that is at the core of Saussure’s semiology and Greimas’s structural semiotics envisages culture in a questionable way when reproduced at the level of Lotman’s cultural semiotics. Cultural semiotics asks at a theoretical level the same question that strangers ask each other when they meet for the first time: where are you from? The social psychology of this question is complicated, but it undoubtedly manifests a drive for attribution, and therefore control. The alien individual is seen as a puzzling novelty, a source of unknown, and therefore as a potential danger. The question “where are you from?” seeks to elicit an answer that will allow interlocutors to ‘case’ each other, turning individuals into tokens of national and socio-cultural types. Of course there is no need for the question to be uttered explicitly, since it is asked implicitly at every new encounter, and about all the signs that compose a person’s social presence. Where is this accent from? Where is this use of words from, and these clothes, and these gestures? Getting to know someone means progressively classifying as tokens of as many types all the signs that compose the person’s voluntary or involuntary signification. Stereotypes, both positive and negative, are among the types that individuals use to ‘interpret’ each other.

As cultural semiotics approaches a text, an object, or a cultural phenomenon whatsoever, it also tends to ‘case’ it as manifestation of a rule, as expression of a socially depositedlangue. The stereotypes that cultural semioticians make use of are much more articulated than those which common people, let alone racist people, resort to. Yet, there is something in common between cultural semiotics and racism, as there is between racism and bureaucracy.

Albeit very different in many respects, these three social practices aim at creating an inventory of reality that categorizes and interprets it without residues. Bureaucracy in western universities, for instance, is churning out more and more complicated forms in order to make sure that each aspect in the life of a student or a professor is attributed to the appropriate class, turned into the token of a type. There is nothing that irritates more bureaucracy, indeed, than the unclassifiable case, whose potential novelty cannot be neutralized by reference to a specific form, set of parameters, range of criteria, etc. etc. This classificatory frenzy, which seems to ape that of natural sciences like zoology or botany, covers increasingly large areas of university life. Students’ learning, professors’ teaching, the use of infrastructures, financial data, every aspect or behavior cannot be left unaccounted for but must be classified and, possibly, numerically treated. Accounting for university life is more and more tantamount to counting university life. Recounting the meaning of the academia does not require a historian anymore but an accountant.

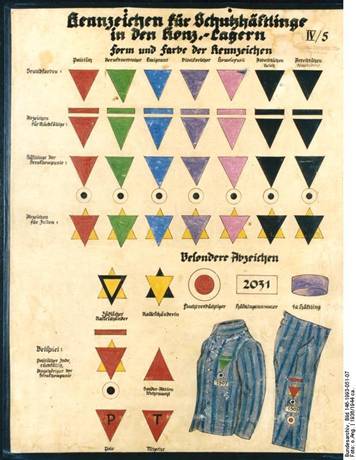

The desire of controlling other people through turning them into tokens of predetermined types finds the most aggressive expression in racism, especially in the institutional shape it took in 20th-century totalitarian regimes. The parallel between bureaucrats and fascists might seem exaggerated, yet there is something in the epistemology of the former than dangerously resemble the epistemology of the latter. All considered, the common epistemological denominator comes down to substantial anti-humanism. Fascisms, like bureaucracies, do not understand individuals and their behaviors independently from the explanatory grid that was predetermined so as to attribute them to a class of individuals and behaviors. The kind of meta-language that fascisms adopt in order to articulate and interpret people racially is therefore intrinsically bureaucratic, and disquietingly resembles the forms of modern bureaucracy. What follows is, for instance, the visual meta-language through which Nazi concentration camps would articulate prisoners according to their race and the ‘crime’ they had committed.

Claiming that racism is always bureaucratic does not imply that bureaucracy is always racist. On the contrary, bureaucracy in modern societies is meant to protect individuals from the idiosyncratic abuse of power. Yet, the semiotic parallel between organized racism and bureaucracy should make us wary of collectivities where the impulse to categorize, classify, and interpret individuals attains increasingly pervasive degrees of sophistication. A society that is unable to accommodate exceptions is a dangeroussociety, perhaps even more dangerous than a society that is unable to come up with rules.

The parallel between organized racism and bureaucracy should warn cultural semioticians too. Medieval scholastic philosophy used to repeat, interpreting Aristotle, “Scientia est de universalibus, existentia est singularium”, “science concerns the universals, existence refers to singular (objects)” or, with another formula: “Nulla est fluxorum scientia”,“there is no science of fluxes”. In order to produce falsifiable hypotheses about culture, indeed, semiotics must elaborate general models where cultural phenomena are interpreted as manifestation of an underpinning semiotic rule. Cultural phenomena must be stripped of their idiosyncratic particularities and cased into a category. Cultural semiotics can of course increasingly refine the articulation of its categorical thinking, but its operations keep resting on a theoretical movement of attribution.

Yet, it would probably reductive to think that cultural semiotics should not be concerned by the existence of singularities, as scholastic epistemology urged sciences to do. On the one hand, the risk that bureaucracy runs when forgetful of the dignity of exceptions, treating them as anomalies, recurs in cultural semiotics too. When cultural semioticians deal with texts, they usually ask them the same question that strangers ask each other when meeting for the first time: “where are you from?” Where are you from, folktale? Where are you from, epic? Where are you from, painting? Where are you from, behavior? What cultural semiotics hopes for as an answer is an indication of where, in the spatial and temporal semiosphere, the object of investigation should be placed and categorized, so revealing its intrinsic meaning in relation to a precise patterning model.

One could argue, though, that asking the question “where are you from” is not the end of the gnoseological process, but the timid beginning of it. Stereotypes and bureaucratic parameters offer a grid to interpret reality, but stopping at them means divesting humanity of its deepest character, means stripping scholarship of its inner beauty. What do we know of a scholar, when we know that he is Italian? Something, but not much. And what do we know of a paper, when we know that is had been quoted twenty times? Something, but not much.

On the opposite, there is a stage in knowledge between two people, at which the question “where are you from?” does not arise anymore. It is the stage of love, or true friendship. At this stage, stereotypes must dissolve and leave space to irony, and the irreplaceable uniqueness of the subject. A subject who, as Lévinas would suggest, is not known anymore as a façade, in its cold splendor, but as visage. Of the architecture of a façade one could argue that follows and embodies a certain style. But saying thus of a visage would bring us back to the dubious investigations of Lombroso, to the Fascist anthropology of the face.

Demanding cultural semiotics to study texts as the visage of a beloved one is perhaps excessively tainted with romantic connotations. Yet, keeping in mind the political danger of turning semiotics into a bureaucracy of cultures is imperative, not only in moral terms – since it reminds us of what humanities are about, and their substantial difference with sciences – but also in theoretical terms. As the forms of university bureaucracy will never be able to tell why a student falls in love with semiotics, or why a professor devotes most of his life to study this discipline, in the same way a cultural semiotics oblivious of its humanistic constraints will be never able to explain how, despite the despotic pressure of the langue, the constraining grid of types, and the thwarting cage of modeling systems, signs and their laws are not solid structures but fluid elements, which do change through history. A science of fluxes is needed to understand them fully.