ON DEPTH: ONTOLOGICAL IDEOLOGIES AND SEMIOTIC MODELS

University of Turin, Italy

The proprioception of space is a major matrix of cognitive and conceptual metaphors. Scholars too often resort to spatial metaphors in order to “place” and “visualize” their theoretical insights. Semiotics is not an exception: on the opposite, given the abstractedness of the semiotic investigation, semioticians have often coated their theories in spatial imaginaire. Peirce’s semiotics could not be conceived without its triangular insistence, the superposition of a representamen upon an object through an interpretant, diagrams, and graphs; Lotman turned space into a meta-language, but was himself thinking semiotics in spatial terms (the semiosphere being the epitome of spatial theorization); as for the trend of semiotic scholarship that develops from Saussure through Hjelmslev to Greimas and beyond, the preeminence of “spatial thought” (perhaps a consequence of the “diachronic primacy”) is evident since the first model of sign, wherein the signifier and the signified are situated in a specific, hierarchic topology. The paper will claim that not only each school of semiotics, and perhaps each semiotician too, refer to a characteristic spatial imaginaire, but also that this theoretical topology interacts with what could be called an “ontological ideology”: in each sociocultural group, at a given moment of its history, a certain conception of being is given preference over the others, generating a spatial imaginaire.

The paper will therefore seek to retrace the intellectual trajectory of Algirdas J. Greimas’s semiotics in relation to one of these ontological ideologies and its spatial figure: depth. Greimas’s theory on – and model of – meaning became international acclaimed – the paper will argue – because successfully intercepted an ontological ideology predominant across societies and cultures in the 1960s and 1970s: according to it, what matters does not lie at the surface of things, but in their depths; in order to reach value, one must dive into this depth, equipped with a suitable methodology, and unveil the essential that is hidden behind several layers of inessentiality. Greimas’s “generative path” [parcours génératif] epitomized the theoretical triumph of such “topological ideology”. With this hypothesis in the background, the paper will seek to explain why the Greimasian method became so acclaimed, why it was subsequently so denigrated, and why and in what guise it should be rediscovered in present-day international semiotics.

A topology is intrinsic to the idea of sign. Variously defined first by philosophers, then by semioticians, the sign must be conceived as relation between two or more dimensions that are not equally accessible to the senses. Such relation can be thought of abstractedly, but as soon as it is described, for instance by the meta-language of semiotics, inevitably takes on a spatial appearance. That is evident above all in meta-semiotic diagrams. Saussure and his interpreters insist that the sign must be conceived as the unity of signifier and signified, which would be like the two faces of a sheet. However, the meta-semiotic diagram that visualizes this relation transcribes it topologically. Moreover, this topology is immediately hierarchical: the signifier is above, the signified below. Hjelmslev’s schematization of the sign is not different from this point of view. The “E” of expression and the “C” of content might be placed on the same line, but always according to the hierarchical, horizontal topology of western reading: from left to right, expression comes first, followed by content, through the slash of function. The hierarchical topology between the various dimensions of the sign is even more conspicuous in Peirce’s semiotics, where it is visually rendered by a triangular structure: from the representamen the mind must climb up the steeped line to the interpretant, which mediates access to the object. However, the mind never descend from the interpretant toward the object, but keeps climbing from interpretant to interpretant, as Peirce makes it clear through the concept of unlimited semiosis.

These topological, hierarchical characterizations all ultimately stem from the predominant ontological ideology of semiotics. Semiotics does not deal with ontologies, but is nevertheless shaped by a certain way of imagining the being, what is. From the pre-Socratic philosophy of the sign until contemporary semiotics, the ontological ideology of the discipline has revolved around the same axiom: what appears is not what is. There is something beyond what appears, and this something is posited as the goal of a narrative quest in which what appears plays an ambiguous role. It is a hindrance, because it somehow veils what is, but it is a helper too, since what is can be accessed only through the veil of appearance. As it will be pointed out later, though, according to semiotics, what appears is not automatically a helper, but it can turn into such if approached through suitable methodology.

In any case, those who partake in the semiotic endeavor must implicitly or explicitly subscribe to this ontological ideology; otherwise they would not be semioticians. Other ontological ideologies are, indeed, possible, but all nullify the semiotic perspective. In some alternative ontological ideologies, for instance, what appears is the being and the being is what appears. There is no way, and no necessity, to go beyond appearance, because the signifier is the signified, the expression is the content, and reality manifests itself through itself, as a language made by referents. Such ontological ideology is unconceivable from the point of view of semiotics, yet is embraced by some trends of the current scientific discourse. For instance, when radical neuroscientists claim that ‘love’ has been located in a certain area of the brain, they somehow endorse an ontological ideology according to which there is no hierarchical distinction between the physiological activity of neurons, the visualization of this activity on the screen of a CAT-scan, and the psychological feature linked with this activity: those neurons are love, and love is those neurons. Such logic is unacceptable for semioticians exactly for it manifests an ontological ideology that is strikingly at odds with that of semiotics, to the point of denying the rationale of the discipline. Indeed, if what appears is what is, and what is what appears, why should the very idea of the sign be entertained?

Another alternative ontological ideology that currently threatens the very foundations of semiotics is apparently more trivial, but perhaps more pernicious than the one that underpins neurosciences. It is the ontological ideology that often manifests itself in the attitude of the mass toward semiotics, and increasingly thus also in the candid reactions of undergraduate students towards the discipline: why should a novel mean something? Why should a movie tell more that its visual brilliancy? Is there really something beyond advertisement’s prompts to buy? In other words: why should one bother with semiotics? Partisans of this ontological ideology are like the protagonists of Flatland, the 1884 dystopian novella by the English schoolmaster Edwin Abbott Abbott, in which people who live in a two-dimensional world encounter people who live in a three-dimensional world. The novella was meant as critique of Victorian positivism, but is still valid: the skepticism of the general audience and many students toward current semiotics is similar to that which the character of the sphere provokes upon its arrival in Abbott Abbot’s Flatland.

Ontological ideologies that compete with the one that underlies semiotics can be arranged in a taxonomy inspired by the squared of veridiction. On the one hand, certain ontological ideologies predicate the perfect coincidence of what is and what appears. It is the typical attitude of scientific reductionism and of all the anti-hermeneutic stands that proliferate in contemporary mass culture: there is no way to distinguish any longer between what is deep and what is superficial, because there is no depth underneath superficiality; what one sees, hears, smells, tastes, touches is what ultimately matters. Those who search for meaning beyond the surface of reality are actually delusional and boring.

On the other hand, other ontological ideologies also conflate the dimension of appearance and that of being but, instead of proclaiming the unity of both into a common dimension, like in positivism, they tend to abrogate them into a sort of mystical vacuum, like in nihilism. It is the ontological ideology of new age spirituality, for instance, but it can be ascribed also to deconstructionist hermeneutics: how could meaning be accessed through the signifier, if both meaning and signifiers are nothing but illusion, constantly recreated by the chaotic riddles of history and discourse?

Two further alternative ontological ideologies distinguish, on the contrary, between being and appearance, between a dimension of reality that is readily accessible and one that is hidden beneath. The first embraces an ontological vision in which what is is more than what appears. In the squared of veridiction, that is the position of secret, which is also fundamentally the position of semiotics. Semiotics, as it was successfully thematized by Umberto Eco both in scholarly works and novels, is the realm of abduction, of adventurous and conjectural investigation. Sherlock Holmes is its hero. Semiotics believes that meaning is not at the surface of reality, but hidden in its depths. However, semiotics also contends that there is a method, a rational way to proceed from surface to depth. In other words, for semiotics the appearance of reality is not all, but can be trusted.

Also according to the fourth and last ontological ideology in the taxonomy, the appearance of things hides a more truthful layer of reality; yet, in this fourth ideology, appearance cannot be trusted. What appears is not what is. In the semiotic square of veridiction, such is the position of lie. It is also the ontological ideology of the so-called conspiracy theories. Supporters of these theories claim, as semioticians do, that meaning is to be found beyond the surface of appearance. Yet, they also claim, differently from semioticians, that appearance is not a reliable channel to meaning. On the opposite, for conspiracy theories there is no rational method to abduce what is hidden from what hides it, since what hides it is conceived not as a helper but as an opponent in the quest for meaning and truth. The disquieting consequence of this ontological ideology is that conspiracy theories are usually unfalsifiable, meaning that they are not conjectural theories as Popper defines them. Semiotic theories are falsifiable because they trust the appearance of the signifier and work with it through a rational methodology. Other semiotic theories can operate differently, and falsify the first ones, exactly insofar as they both trust and work with the same signifying materials. That is the core of inter-subjectivity in semiotics. Yet, that is not the case with conspiracy theories. The surface of things is just discarded, and a hidden meaning fabricated with no relation with appearance.

The following diagram summarizes the four ontological ideologies described thus far:

|

|

Being and appearance do not coincide |

Being and appearance coincide |

|

Appearance is reliable |

SECRET / Semiotics |

TRUTH / Positivism |

|

Appearance is unreliable |

LIE / Conspiracy Theories |

FALSITY / Nihilism |

A Taxonomy of Ontological Ideologies.

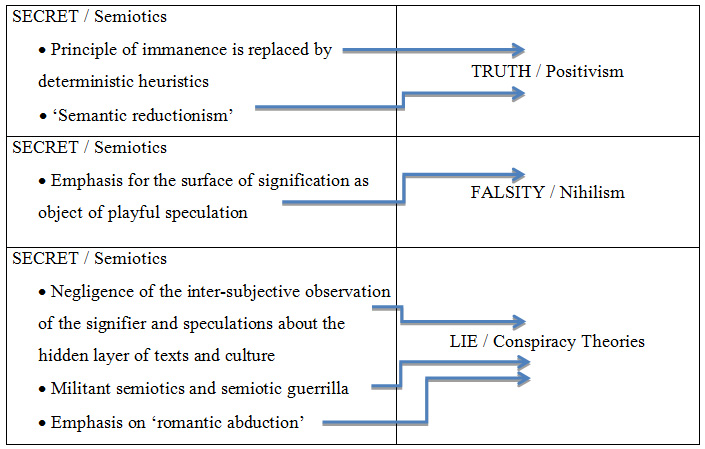

This taxonomy is not meant as a point of arrival but as one of departure. Several questions can be asked about it. Some of them concern the structure of the taxonomy, for instance, the way in which different types of hermeneutic discourse can be placed in the frame. Indeed, whereas the taxonomy associates semiotics with the ontological ideology and the epistemology of SECRET, it must not be read as a rigid grid, but as a dynamic scheme, where each quarter is separated from the others by thresholds more than by neat frontiers. Thus, as semiotics relinquishes its scientific attachment to the inter-subjective observation of the signifier and delves into speculations about the hidden layers of texts and culture, it resembles more and more a conspiracy theory. Such is the case of certain analyses offered, especially in the 1970s, by militant semiotics, or by semiotic guerrilla, where passionately denouncing an enemy ideology was even more important than coldly dissecting its language.

The same goes for semiotic theories that exceedingly emphasize the role of abduction in the passage from surface to depth, from appearance to meaning. Such is the case of Peircean semiotics, mainly in the interpretative version of it proposed by Eco, when focuses on romantic intuition more than on analytical method. William of Baskerville in The Name of the Rose still is a semiotician, although heavily resorting to abduction; yet, Robert Langdon in The Da Vinci Code is not a semiotician any more but a conspiracy theorist. The fact that nowadays the latter is more read and appreciated than the former is telling of the place of semiotics in the popular imaginaire.

In the same way, as semiotics, in its structural version, abandons the principle of immanence and endorses deterministic heuristics, be they neurophysiological or economic, it dangerously moves toward the area of reductionism. A symmetrical drift carries semiotics to forget the signifier and to turn into a sort of “semantic reductionism”. That has been the fault of certain trends of generative semiotics, when they adhered to the principle of immanence so strictly that they became oblivious of the surface, and of the indispensable feedback that it provides for the falsification of interpretative hypotheses.

Third, and last dynamic: when semiotics revalues the surface of signification to the point of detaching its analysis from that of the semantic level, thus turning the signifier into an object of playful speculation, then semiotics risks to step across the threshold that separates it from the nihilism of deconstructionism.

The following diagram offers a visual summary of the tensions that agitate the taxonomy of ontological ideologies:

Dynamic tensions among ontological ideologies affecting the semiotic epistemology.

The publication, in 1966, of Algirdas J. Greimas’s Sémantique structurale marked a breakthrough in the history of semiotics as the most ambitious attempt at capturing the laws that organize meaning in view of its expression. In the first diagram sketched above, the ontological ideology underneath Greimas’s epistemology and methodological proposal situates itself at the core of the semiotic quarter od SECRET: the immanence of meaning and its manifestation are held as two separate dimensions, but a rational, systematic way to connect the former with the latter is viable. In a nutshell, indeed, Greimas’s structural semantics is nothing but an extraordinary effort to introduce inter-subjective control in the human study of signification. In Greimas, signification is not reduced to its materiality, like in positivism; it does not disintegrate because of the slipperiness of both signifier and signified, like in deconstructionism; and it does not feature a mysterious, impenetrable relation between appearance and being, like in conspiracy theories. In Greimas’s structural semantics, on the contrary, meaning is like an intricate jungle that, nevertheless, thanks to the analyst’s titanic patience, progressively reveals its order, its patterned nature, and the laws that turn an array of invariants and variations into the fabric of signification, into the ordinate path between the manifestation of meaning and its immanence.

The question whether Greimas’s confidence into the orderliness of signification was solidly grounded has engaged some among the best minds of the last quarter of 20th century, including Derrida and Eco. With hindsight, though, what mostly matters after almost fifty years since the first publication of Sémantique structurale is not to reappraise its intrinsic value, but to reevaluate it in the frame of a meta-semiotic effort, meant to articulate together ontological ideologies, epistemological proposals, and persistence of ideas through history.

There is little doubt that in 1966, when Sémantique structural: recherche et méthode was first published in Paris by the prestigious publisher Larousse, an audience for this proposal already subsisted, and was conquered by it forcefully, despite the undeniable difficulty of the meta-language. Thanks to Paolo Fabbri and Pino Paioni, the core of Greimas’s proposal was made available to the Italian audience already in 1967, through the booklet Modelli semiologici [semiological models], published by Argalìa, in Urbino, in 1967. Then, the first full translation of Sémantique structurale was also Italian: Semantica strutturale: ricerca di metodo, by Italo Sordi, published by Rizzoli, in Milan, in 1969. In order to retrace the seismography of ideas, details in the history of their publishing are extremely telling; Rizzoli was, and still is, one of the most prestigious Italian publishers. It being the publisher of the first Italian translation of Sémantique structurale indicates the central place that the Italian intellectual arena immediately offered to this methodological proposal. However, it is equally telling of the persistence of semiotic ideas that they currently find space mostly by small publishers around Europe.

In the 1970s, on the contrary, Greimas’s work found editorial space by several European prime publishers. In 1971, Gredos, one of the most credited Spanish publishers, published Alfredo de la Fuente’s translation of Greimas’s Sémantique structurale: Semántica estructural: Investigación metodológica. The same year, in 1971, Jens Ihwe published a German translation: Strukturale Semantik: Methodologische Untersuchungen. The translation appeared by Vieweg Verlag in Braunschweig, an old and prestigious publisher specialized in the publication of the writings of great scientists like Albert Einstein and Max Planck. That reminds one of how Greimas’s proposal presented itself and was welcome in Europe: as a scientific method for the analysis of meaning. The fact that nowadays no semiotician could advance the same pretense without being received with skepticism, irony, or even irritation reveals another feature of the semiotic trajectory in the history of ideas.

In 1973, Haquira Osakabe and Izidoro Blikstein published a Portuguese translation, Semântica estrutural, in São Paulo, by Cultrix and Edusp. As it is evident, the history and geography of these publications reconstitutes a map of how the School of Paris was about to spread in the following years, with strong concentrations in Italy, Brazil, Spain, but also Denmark and Finland. Gudrun Hartvigson translated Sémantique structurale in Danish in 1974. It was published by Borgen, in Copenaghen, under the title Strukturel Semantik. In 1979, Eero Tarasti published a Finnish translation, Strukturaalista semantiikkaa, by a publisher called “Gadeamus”.

Adopting Lotman’s model of cultural semiotics, one could say that, between the second half of the 1960s and the late 1970s, the semiosphere of continental Europe, and especially that of Latin and Scandinavian countries, was dominated by structuralism, and that Greimas’s methodological proposal succeeded to gain its core.

Scrolling this list of translations, though, one is prompted to ask: what about English? What about the language that, already in the mid-1960s, was becoming the vehicular language of the world, first in mass culture, then also in the scientific discourse?

The first English translation of Sémantique structurale was published in 1983, by the time Greimas’s Du Sens (1970), Maupassant (1975), Sémiotique et sciences sociales (1976) the Dictionnaire (1979), and Du Sens II (1983) had already been published in France and translated into several languages – mostly Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese – redefining at each new publication the perspective of Greimas’s theory. The English translation appeared in Lincoln by University of Nebraska Press, a fine publisher that nevertheless does not compete with the giants of US academic publishing. The main translator, and author of the introduction, Ronald Schleifer, was, and still is, Professor of English at the University of Oklahoma. How to explain such delay and somewhat peripheral publication?

Greimas’s meta-language was hard but not impossible to translate, as it is demonstrated by the rapidness and quality of translations in other languages. Moreover, the book mainly bears on a corpus of French examples, Bernanos’s novels, but that was not a problem in English either. Le journal d’un curé de campagne [The Diary of a Country Priest], published in French in 1936, had been translated into English immediately, in 1937.

In order to find an answer, it is interesting to analyze how translations rendered the title of Sémantique structurale. Indeed, this first title is followed by a secondary title, that in French reads: “recherche et méthode” [“research and method”]. The Italian translation of it had already downplayed its assertiveness: “research and method” became “ricerca di metodo” [“research of a method”]. However, the ambition of Greimas’s title was toned down especially in the English translation: “An Attempt at a Method”.

In December 1984, the journal Modern Languages Notes published a lucid review of this English translation. Robert Con Davis, also Professor of English at the University of Oklahoma, convincingly explained why Sémantique structurale was translated so late into English, so peripherally, and so timidly. Already in 1975, Jonathan D. Culler had published Structuralist Poetics, appeared by one of the most central US academic publishers, Cornell University Press. In 1976, one year later, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak had translated, also for a major US academic publisher – Johns Hopkins University Press – Derrida’s De la grammatologie, which was originally published, nevertheless, in 1967, one year after Sémantique structurale. The geography of the US translation of French scholarship therefore distorted its chronology: whereas Derrida’s deconstructionism was a reaction to structuralism, in the US, Greimas, who was the founder of structural semantics, was presented to the English readership as a somewhat vintage post-structuralist reaction to deconstructionism. Paradoxically, the US audience became familiar with deconstructionism before knowing structuralism, and knew structuralism only as a post-deconstructionist, post-structuralist wave.

History and geography of publishing are symptoms of intellectual evolutions, but do not fully explain it. The question remains of understanding why Greimas so forcefully struck a chord in the cultural semiosphere of 1960s and 1970s continental Europe, why it didn’t in the UK and in the US, and why, also in continental Europe, it lost momentum from the 1980s on. However, the most important question is the one that revolves about the legacy, and the prospects, of Greimas’s ambitions.

There is no clear-cut answer to these questions. In relation to the taxonomy of ontological ideologies proposed above, every switch or slide of paradigm fulfills different historical and anthropological needs. The sum of these changes brings about an alternation of ideologies where each reacts and succeeds to the previous one and simultaneously prepares and is cast aside by the next one without any clear indication of either agency or teleology.

What can be argued is that 1960s and 1970s readers and followers of Greimas enthusiastically adhered to an ontological ideology according to which communities can rationally debate about the perception of what appears in relation to the meaning of what does not. Later on, this trust in rationality, inter-subjective transparence, and universalism inexorably dwindled. On the one hand, Greimas’s popularity was undermined by the reaction of deconstructionism, amplified by the enormous popularity it gained in the US, mainly through providing theoretical support to various ideological claims (colonial studies, gender studies, post-Marxism, etc.). On the other hand, Greimas’s proposal was either stiffened into a “semantic positivism” or attached to reductionist theories.

Whereas deconstructionism denounced the hubris of Greimas’s universalism, reductionism anchored it exclusively to the study of nature. Greimas’s dream – which was also the dream of Saussure and Hjelmslev – to elaborate a rational but nevertheless social and cultural study of meaning, seemed lost.

However, a partisan of Greimas’s theoretical efforts could claim that intellectual history is currently turning page again, and that soon societies might rediscover Greimas, and Greimas’s school, as a way out from the hermeneutic standstills of deconstructionism, reductionism, and conspiracy theories. In Europe as well as in the US, deconstructionism served a purpose in denouncing the encroachment of power in the sphere of language, meaning, and culture, and in advocating an emancipatory hermeneutic stand. However, merciless critique of structuralist universalism on the one hand brought about the progressive colonization of social sciences and humanities by hardcore scientific reductionism; on the other hand, it opened the gate to all sort of conspiracy thought and shameless revisionism. A dim consequence of the marginalization of any rational ambition in the humanities is that neo-positivism is still unable to tackle, let alone answer, the social demand for knowledge about meaning; simultaneously, conspiracy theories continue to muddy the waters of public discourse, giving the impression that no rational way exists to choose among competing hermeneutics.

Rediscovering Greimas in the international discourse of present-day semiotics means affirming the need for a new inter-subjective pact, for a new rationality, and also for a new universalism. If the world seems to speak an increasingly chaotic language, international semiotics should not add chaos to chaos, but revive with new energies and increased self-awareness an era in which linguists and semioticians thought that the way to comprehension and agreement was indeed difficult, but nevertheless possible. That the world had depth, separating appearance from being, manifestation from immanence, expression from meaning, but that semiotics had sufficiently strong lungs to dive into this depth and come up to the surface with a rational answer.