THE SEMIOTICS OF RELIGIOUS AMAZEMENT

University of Turin, Italy

Abstract

The article posits amazement as definitional dimension of the religious experience. Starting from Hjelmslev designation of content, and re-elaborating it in its dialectics with the ‘container’ (expression), the article proposes that often religions situate believer in a maze whose cognitive and emotional effect is awe. At the same time, paradoxically, religious traditions also often propose a recipe to recompose wonder into a transcendent diagram. The sand drawings of Malekula, studied by abundant anthropological tradition, are reinterpreted from a semiotic perspective, deciphered as ‘amazement devices’, and compared with similar sacred diagrams.

In Hjelmslev’s version of Saussure’s structuralism, the terms “expression” and “content” replace those of “signifier” and “signified”. A topological metaphor is introduced in the description of the sign, as though the signified was something that must not only be signified but also “contained”. When semiotics is applied to the study of religious texts, languages, and cultures, one is left wondering whether such topological metaphor of containment could not be pushed further, namely, replacing the term “expression” with the term “container”. Imagining the sign as a relation between content and container might seem to betray Saussure’s belief in the substantial unity of the two faces of signification.

Nevertheless, that is the case mostly if the container is imagined as a sort of box, as a receptacle that human communication fills with semantic items so as to transport them elsewhere. Yet, there is another way of interpreting the ‘containment’ of signification. The ‘container’ should be imagined not much as inert box, but as pattern of forces whose aim is, above all, that of containing other forces. In this case, though, “containing” is to be interpreted not only in the sense of “holding”, but also in the sense of “restraining”.

The restraining action that the signifier/container exerts on the signified / content is best conceived with relation to the French paleontologist André Leroi-Gourhan’s philosophy of techniques. In his 1943 L’Homme et la matière [Humans and Matters], he developed a philosophical hypothesis on the anthropology of weaving, considered as trans-cultural technique through which human beings manifest the sense and the practice of order that they have attained through evolution. Deleuze and Guattari philosophically fleshed out this line of anthropological reflection in a passage of Mille plateaux [A Thousand Plateaux] (1980), where they define the opposition between“espace lisse” [smooth, unrippled space] and “espace strié” [ridged, rippled space]. According to the two philosophers, human techniques that create “rippled space” are essentially techniques of control, centered on the sense of view, whereas the sense of touch is put in relation with unrippled space and haptic phenomenology. Following this hypothesis, Leroi-Gourhan’s interpretation of weaving indicates one of the first steps in a long cultural evolution, through which humans have sought to impose a visual order on the disquieting chaos of nature, including their own human nature. The invention of perspective would be another major step in this anthropological evolution.

Taking the lead from Leroi-Gourhan and Deleuze & Guattari, the anthropology of rippling could be generalized, in view of a new definition of the sign as relation between content and container. From this point of view, signification would result from the human attempts at controlling the forces of the environment. That seems to overturn the intuitive conception of signification, which is mostly thought of as a way to give course to communicative intentionality; as positive dynamic. The definition of the sign as containment technique, on the contrary, focuses on signification as elaboration of hindrances; as negative dynamic.

In hindsight, an intuition of this negative dynamic is also in the word “expression”, which etymologically refers to a “pressing out”, and therefore to the presence of an obstacle, a contrasting force, without which such pressing out could not take place, exactly as a hard object must be pressed against an orange in order to squeeze the juice out of it. This intuition of the negative side of signification is certainly present in Peirce, in the distinction between immediate and dynamic object, but is not absent either in structural definitions of the sign. In structuralism, indeed, the hindrance that enables signification is nothing but the grammar, or the code.

Conceiving signification as constraint, more than as possibility, might be fundamental in the specific but vast field of the semiotics of religion. Being a branch of cultural semiotics, the semiotics of religion works along two apparently opposite directions. On the one hand, singling out, describing, and interpreting signs, texts, and languages that develop across religious denominations, so as to understand to what general anthropological or cognitive need they respond. On the other hand, classifying differences, showing how historical and contextual pressure has brought about specific forms. For instance, on the one side, semiotics is interested in the catholic rosary as the cultural-specific token of a broader type, where counting devices belonging to different spiritual traditions are to be subsumed. On the other side, semiotics focuses on the peculiar morphology that this device takes on in Catholic contexts, considered either in their historical evolution or freezing a phase of them into a synchronic section.

Both tasks are complicated, but their difficulty is of different kinds. Whereas the comparative work necessitates systematic perusal of historical and anthropological data, as well as a solid semiotic framework of analysis and interpretation, the generalizing, cross-cultural endeavor cannot escape speculation in the domain of the semiotic philosophy of religion. Semiotics indeed has not only the ambition to provide linguistic, textual, and semiological skills to those who interpret signs in religion; it also cultivates the higher ambition of coming up with a definition of religion sub specie signi [from the perspective of the sign].

The latter task is complicated for not only the definition of religion, but also its own semantic field is culturally biased. What groups of phenomena individuals, cultures, and even scholars and societies of scholars decide to categorize under the label “religion” is not at all a matter of fact, but outcome of complex and not always transparent negotiation. The fact that nowadays Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, and New Age might all be classified, and studied, as “religion”, results from this invisible negotiation. Present-day political and legal controversies about whether Scientology or Falung Gong should also fall in the same category show that this negotiation is ongoing, accompanied by power struggles and heavy social consequences.

To this multi-dimensional polyphony, the semiotics of religion adds a fresh voice, unburdened by the influence of theology, history, or anthropology, while looking at them with attention and respect. Faced with the task of determining the quintessence of religion, semiotics must come up with a philosophical hypothesis that rests, nevertheless, on the empirical and inter-subjective observation of signification processes. Given the range of cultural phenomena that the current scientific discourse ascribes to the semantic field of “religion”, what semiotic features appear cross-culturally throughout these processes? And what features, on the contrary, make them unique or separate them into groups and families? Moreover, what new rearrangements, both at the cross-cultural and at the comparative level, are made viable by the introduction of the semiotic perspective?

It might be ventured that one of the common denominators of religious phenomena, considered from a semiotic point of view, is amazement. There is something amazing in every religion. Of course, such amazement should not be defined simply as emotional response, but as semiotic process connecting the religious experience, language, and the human cognition. A clue to a better definition of amazement is in the etymology of the word. Semanticists know well that the etymology of a word does not always correspond to its current semantic field. Yet, it provides an indication about what cultural trends have shaped the meaning of the word throughout history, thus turning the word itself into a knot in a culture’s evolution.

In Old English one finds the verb amasian [“confuse, surprise”] and its past participle amarod [“confused”]. Significantly, 19th-century etymologists referred the word “amaze”to Old High German meis, which used to designate “a basket carried on the back”. Later, the Norwegian etymological dictionary by Falk and Torp indicated among the meanings of mase “lose consciousness” and “become delirious”.

Two semantic lines, hence, intersect in the etymology of “amazement”: on the one hand, a reference to the patient activity of weaving; on the other hand, a reference to loss of mental control. The former can be related to the constraining dimension of semiosis, already evoked above through Hjelmslev’s meta-linguistic choice of “content”, Leroi-Gourhan’s emphasis on weaving as the technique that models the human conception of orderly cultural patterns, and Deleuze & Guattari’s views on the fabrication of ‘rippled space’. The latter element, that is, loss of mental control, is equally central in the semantics of amazement. That is why the lexeme “maze” has been extracted from the verb“amazement”. A naïve etymology has the verb “amazement” derive from “maze”, but historically the reverse is true. “Maze” in English designates an amazing place, that is, a place whose intricate weaving represents a challenge to mental control.

To this regard, it is interesting to notice that English, unlike other languages, distinguishes between labyrinths and mazes. Although the semantic line separating the two is thin, the first word is usually referred to intricate spatial structures where nevertheless a single path inexorably leads from entrance to goal; the second word, on the opposite, usually designates complex spatial structures that provide a multiplicity of choices. The spatial structure of labyrinths is usually unicursal, meaning that it can be traced in one continuous line; the spatial structure of mazes, instead, is usually multicursal, meaning that it cannot be traced in one continuous line.

Both labyrinths and mazes are designed to prompt a cognitive, emotional, and pragmatic response, but in different ways. Upon entering a labyrinth, one does not know whether its path will take to the goal; one therefore continues to walk through it, anguished by ignorance, while every twist adds to the feeling of spatial and emotional disorientation. However, finding the exit in a labyrinth is a matter of faith, whereas finding the exit in a maze is a matter of both faith and choice. In a maze too there is no certainty that the path will take to the goal, but the anguish of the labyrinth is increased by necessity of choice; at every turn, one fears that the wrong decision has been taken. That is why maze in German is called Irrgarten or Irrweg [litt. the garden, the way of erring].

Distinction between labyrinths and mazes helps to more precisely define the semantics of amazement: if maze is the spatial matrix of amazement, then amazement originally is the emotion of feeling lost in front of a vertiginous multiplicity of choices. The current semantics of amazement, though, tends to bear a positive connotation. “Amazing” is what wonders and surprises in a positive way, generating a feeling of euphoria. However, the euphoric tone of amazement should not surprise. After all, both labyrinths and mazes turn often into playful places exactly for they provide narrative potentiality. Complicated as they may be, indeed, they offer human beings the perfect spatial metaphor of faith and will overcoming ignorance and adversity. The vertiginous thrill created by the meandering structure of the maze adds to the existential fulfillment that one attains coming out of it.

On the basis of these considerations, the semiotic definition of religion as the human dimension of amazement can be more analytically explained. Like a maze, religious cultures often present believers with an intricate pattern, which manifests itself through the words of sacred texts, the movements of liturgy, the gestures of prayer, etc. Like in mazes, there is something both anguishing and playful about these patterns. On the one hand, the structure of the religious maze seems to constantly remind believers that they are confronted with vertiginous, overwhelming infinity. On the other hand, the religious maze provides believers with a narrative vade mecum. That does not simply mean that religions show the way out of the maze they construct, which would be a trivial interpretation of their role. More subtly, it can be argued that the religious maze represents the extraordinarily complex simulacrum of a key existential feature of the human species.

Peirce sought to capture it through the concept of unlimited semiosis. The perennial, unstoppable flight of interpretants is not an exception in human cognition, but the rule. Not only human beings cannot stop thinking, but thought most frequently unfolds in apparently chaotic, unsystematic way, exactly like the meandering structure of a maze. Such mental proliferation is indeed at the core of human linguistic ability, and has proved the most effective feature of the human species throughout evolution.

Interestingly, Umberto Eco has labeled “fuga di interpretanti” [litt. “fugue of interpretants”] this erratic burgeoning of interpretants. “Fugue” is both a musical term, designating the contrapuntal composition mastered by Bach, and a psychiatric term, indicating the loss of one’s identity, the sinking of the psyche into anguishing disorientation. These two semantic lines seem to reproduce those that intersect in the etymology of “maze”: on the one hand, the frightening feeling of losing mental control; on the other hand, the playful evocation of infinity as something that can be traveled through, guided by faith and cunningness. Deleuze & Guattari’s critique of ‘rippled space’ was indeed also a complex eulogy of the theoretical virtues of mental derangement, which the style of Mille Plateaux embodied against the capitalistic drive to control and its visual devices, from the perspective to the panopticon. As Umberto Eco has underlined in its typology of the labyrinth, the decomposition of its containing structure brings about the rhizome, which is exactly the cognitive model endorsed by Deleuze & Guattari.

However, classifying religions as instances of ‘rippled space’ that seek to canalize the human inclination to mental erraticism would be reductive. Religions are conglomerates of interpretive habits, but they are not only that. On the contrary, from the semiotic point of view, religions seem to play a double, paradoxical role. They place believers in a maze, but simultaneously they provide them with an aerial view of it. For the believer, the existential experience of being immersed in a complex matrix that elicits an emotional response of disorientation, awe, and even fear is inseparable from a euphoric vision of order, be it the unicursal order of a labyrinth, when religions interpret existence as destiny, or the multicursal order of a maze, when they consider it as choice. Playfulness is germane to religions for play too features this constant shift from two paradoxically co-present dimensions of immersion and detachment, vertigo and control.

Given the human adaptive capacity for burgeoning thinking, religions provide narrative frameworks in which such capacity is both vicariously exalted and tamed. From this point of view, the religious experience is inextricably linked with the linguistic one, for language too is, structurally, infinitude and control, proliferation and grammar, maze and labyrinth. The abstract coincidence of language and religion confirms the need for a semiotic perspective on both, but simultaneously underlines two responsibilities, linked with the two dimensions of semiotic research evoked above.

First, the parallel between religion, language, and mazes must be supported by empirical evidence from the interconnected study of nature and culture. The neurophysiology, cognition, and cultural elaboration of infinitude must be studied in their reciprocal influences. Second, semiotics of religion faces a comparative responsibility: if religion is a maze, semiotics must observe and analyze every turn of it in order to come up with an articulated classification of both patterns and practices. The maze that Judaism proposes to believers is different from that of Christianity. They share a general principle, but they embody different conceptions of infinitude, path, choice, goal, destiny, etc.

Returning to Hjelmslev, the semiotics of religion is after the form of each religious maze, as well as after the evolution of this form through history and contexts. But here“form” should be meant according to the Danish linguist’s original conception, not as pattern that has already shaped a certain matter, that is, as substance, but as constraining scheme before any substantiation. For instance, the semiotician of Christianity is interested not as much in the structure of liturgy in 17th-century mass, as in how this structure translates into verbal and gestural codes a more abstract framework, which can be extracted from those codes and identified as the early modern Christian form of religious experience. The difficulty of the operation derives from the fact that Hjelmslev’s cultural forms cannot be perceived as separated from the matters they shape, and must therefore be excerpted from them. Yet, that might be the most important specific contribution of semiotics to the study of religious phenomena: pinpointing how the containment of infinitude is arranged in each religious culture, tradition, period, and context, through which articulatory maze or labyrinth.

The risk of getting lost is even higher in this enterprise than in that of navigating through a medieval maze. Yet, a good point of departure is represented by the explicit diagrammatic representations that often circulate in religions. In several cases, indeed, religions adopt diagrammatic expression in order to communicate the skeleton of their inner form, as though providing a fractal miniature map of the maze they immerse the believer into. What follows is an example of the diagrammatology of the sacred that semiotics should carry on in a comparative and systematic way.

There is no lack of attention in semiotics toward labyrinths and mazes. Umberto Eco devotes paragraph 2.3.5 of his Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language to “The Encyclopedia as Labyrinth”, proposing a typology of labyrinths, mazes, and rhizomes as well as positing the encyclopedia as model that captures the “flight of interpretants”. The title of one of Eco’s last books on the semiotic theory of knowledge, From the Tree to the Labyrinth, also bears on the topic. Curiously, Peirce too devoted attention to mazes, however not in order to explain them, but in order to construct them. In 1909 he published in The Monist an article entitled Some Amazing Mazes. A Second Curiosity. The article consists in the thorough description of how mathematics can be used to create sophisticated and ‘amazing’ card tricks. One should not forget either the deep influence that Borges’s imaginaire, so replete with labyrinths, exerted on contemporary semiotics.

However, while Eco’s epistemological insights on the gnoseology of labyrinths might remain in the background of an enquiry about mazes in religion, and Peirce’s own mazes provide further evidence of the American semiotician’s exuberant diagrammatics, the primary concern for the semiotics of religion is to analyze the various schemes through which religious cultures represent their own abstract form.

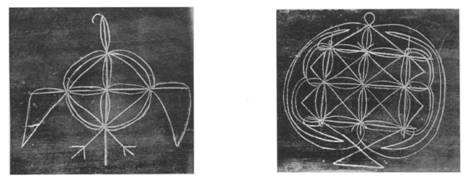

The sand drawings of Malekula are an exemplary case study. Malekula is the second-largest island in the nation of Vanuatu, in the Pacific Ocean region of Melanesia. Male natives traditionally engage in the production of extraordinarily complex and skillful sand drawings. Here follow some examples (figures 1 and 2):

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

These drawings have been a key object of anthropological inquiry at least since 1914, when the British ethnologist John Layard recorded some of them during his visit of the New Hebrids, now Vanuatu. Christian missionaries had already produced sketches of these drawings and sent them to the attention of the British ethnologist Alfred Cort Haddon. One of his students, Bernard Arthur Deacon, first gathered extensive documentation about them during his stay in the island between 1926 and 1927. As Deacon wrote in one of his notes, edited and published after his premature death in 1927 by British anthropologist Camilla H. Wedgwood: “The whole point of the art is to execute the designs perfectly, smoothly, and continuously; to halt in the middle is regarded as an imperfection […] Each design is regarded rather as a kind of maze, the great thing is to move smoothly and continuously through it from starting-point to starting point.”

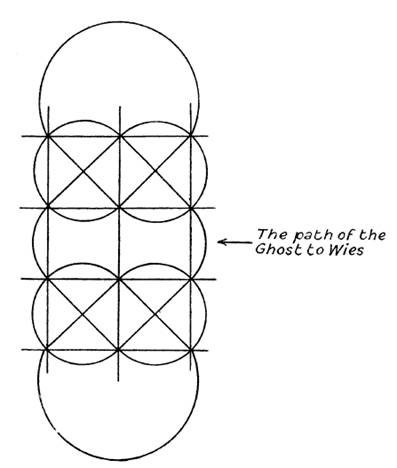

In the same notes, Deacon reports a local myth that points at the religious relevance of the drawings. When people from the Seniang district of Malekula die, they must reach Wies, the land of the dead, through a specific road. At a certain point along the way, they come to a rock called Lembwil Song, lying in the sea at the boundary between the Seniang and Mewun districts. The land of the dead is situated behind the rock, surrounded by a high fence. Sitting by the rock is a female ghost, Temes Savsap. On the ground in front of her is drawn the complete pattern know as Nahal, “the Path” (figure 3).

Fig. 3

The path that the deceased must go through so as to accede to the land of the dead lies exactly in the middle between the two symmetrical halves of the drawing. But as soon as the dead approaches it, the female ghost hurriedly rubs out one half of the pattern, so that the dead cannot find their way any longer. Only precise knowledge of how to redraw the missing half of the pattern will enable the dead to see the path again. However, if dead people do not know how to complete the pattern, the female guardian of the path eats them, so that they will never reach the land of the dead.

A vast anthropological literature bears on the sand drawings of Malekula, including Layard’s 1942 classic Stone Men of Malekula. This literature indicates how the complex patterns ritually drawn and redrawn by Malekula natives serve multiple purposes: as graphic mnemotechniques, they transmit traditional knowledge about the mythical history and geography of the island from generation to generation; as pastime, they structure the rhythm of existence in Malekula; as complex craft, they determine a hierarchy of skills and wisdom; as abstract diagrams, they enable a practice of concentration and contemplation; as mythograms, they represent formulae for dealing with the afterlife, as is evident in the myth reported above.

From the semiotic point of view, it can be argued that the visual patterns and the performativity of these drawings embody the essential form of Malekula spirituality, the wayin which the local religious culture seeks to both contain and restrain, within a ritual shape, the specific relation that is posited between life and death, immanence and transcendence, infinitude of forms and finitude of drawings. The sand drawings of Malekula are therefore patterns of amazement in the sense that was evoked before: they playfully represent the maze of potentialities that human life implies, and simultaneously transmit ritual knowledge about how this maze can be navigated through. The extraordinary feature of these sand mazes is that they are successfully traversed by the same gesture that create them, as though embodying the inextricable interconnectedness of existence and labyrinth: as soon as the finger touches the sand, it starts creating a maze for itself, but spiritual wisdom will allow the same finger to come out of the sandy maze without mistakes. The maze therefore functions according to both its etymological roots: it is a place of potential confusion, but it is also weaving, pattern that instructs on how to proceed from the entrance of life to its goal.

Building on existent and copious anthropological literature, the semiotics of religion should pursue multiple aims. First, analytically describing the grammar of these drawings, the way in which their lines, curbs, dots, and passages are articulated, nominated, arranged, and associated with a semantic plane of narratives and a pragmatic level of performativity. Second, pointing out how each of these drawings work as pattern of amazement, playfully situating ritual designers in the middle of a maze while providing them with traditional knowledge about navigating through it. Third, formulating hypothesis on how these visual patterns embody the abstract form of Malekula religiosity, its peculiar way of solving the riddle of relation between life and death, infinity and finitude, thought and language. Fourth, the cultural semiotics of religion should engage in the difficult task of comparing different religious mazes and their diagrammatic expressions.

Several religious cultures adopt complex visual patterns in order to have believers ritually experience the amazement of spatial vertigo while providing them with performative control over them. The yantras of Tantric Buddhism are a good example, as well as the diagrammatic decorations in the icons of Byzantine hesychasm. There is a common denominator in these visual and ritual constructions, a similar way of evoking the core of religious experience through a paradoxical simulacrum. At the same time, each of these patterns, and the performative practice that they entail, inflect the principle of the maze in a peculiar, religion- and context- specific way.

The semiotics of religion should look at both these dimensions of commonality and variety, and engage in its own labyrinth of recognition and surprise.