CONNOTATIONS OF EQUATED SIGNS IN MODERN URBAN SPACES

Sergio Marilson Kulak

Londrina State University, Brazil

sergiokulak@gmail.com

Miguel Luiz Contani

Londrina State University, Brazil

contani@sercomtel.com.br

DirceVasconcellos Lopes

Londrina State University, Brazil

dircevl@sercomtel.com.br

Maria José Guerra de Figueiredo Garcia

Londrina State University, Brazil

majogue@uol.com.br

Abstract

This study is aimed at analyzing the potential influence on the representation resulting from the visual transformation undergone by the urban space in Londrina (Paraná state, southern Brazil) because of the implementation of a project for removal of publicity signs from the visual landscape in which they had been present for decades. The city population is 500 thousand inhabitants, and it ranks the fourth largest in that region of the country. A presupposition is that the urban signs become “emptied” inasmuch as their prime signification is shifted onto newer understandings when a connection is made with what is suggested by Roland Barthes’s concept of mythologies. In the case under study, the urban aesthetics is in focus, being that the notion of excess stops connoting the senses of luxury and sophistication, and starts to suggest the idea of surplus, leftover, remainder, all resulting in visual pollution. The study is exploratory in nature and phenomenological in method. Photography is utilized as a resource for data gathering and analysis support. The concept of symbolization is a key element to describe the process of representation of the city image.

1. Introduction

Understanding the city as home to an immense variety of signs that spread in polyphony,means to look atpublicity and advertisement messages as a considerable source of urban language. Signs can be found on the roads, avenues, shops, buildings, indoors or on the street, all over, in a permanent invitation for interpretation and (re)signification. On the other hand, the removal of publicity signs from a visual landscape in which they have been present for decades, superimpose a set of new connotations onto the landscape, as was the case of the ProjetoCidadeLimpa (Clean City Project) adopted recently by some large and medium size Brazilian cities like São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Curitiba and Londrina.

The urban phenomenon is experienced through the manifestations that occur in cities. In the daily flow – the crowds, the vehicle traffic, the buildings that emerge through the pathways, the nature that expands in the squares, fields and roads and the interrelations between individuals that populate the urban – manifest the changes that manconstantly foments in the environment, such as buildings, streets openings, the population and the consumption of the city as a whole.When something is removed from the visual field,a “meaningful absence” is created – which is what this study seeks to understand.

Gradually, the cities enhance the imagination of its residents and visitors, with many signs that perform different operations in the mind of the viewer, among them, the signs of commercial messages. The pathwaysare filled with commercial establishments, formerly with small stalls and groceries to hypermarkets and malls of today. The signs emerge and proliferate stimulating the sale and consumption of goods and / or services, with publicity constituting a strong component of urban image.

By showing themselves as a differential in the sales process, brands began to increasingly exploit this feature, characterizingit as a strong element of acceptance and extremely effective in convincing the consuming public. The publicityreached the streets, and the brandsstarted to use the physical spaces, as also the city pathways to promote the services, and the media used are posters, displays, billboards, signs, up to the use of technology with digital dashboards, interactive shop windows and other formats.

What is relevant, however, is to estimate how the publicity acquires a capacity to transform the urban space, by making variations that can modify the imagery speech of these environments; it hides the senses settled in space with the customs and habits obtained through time, transmuting the environment for the meanings that become commercial, and no longer the matters that were endeavor by city residents.

Picture 1: Higienópolis Avenue (Londrina), GlebaPalhano way, before the implementation of the Clean City Law

Source: JanelaLondrinense. Photography: Roberto Custódio.

The transformations reach alarming levels, to the point of some Brazilian cities awaken to the interest in promoting a visual cleaning to the environment, in other words to establish parameters for placing advertisements in the city ambience, occupying the streets, the urban ways, and not those commercials that have taken arbitrarily, the entire city. It leads to a concern about the use of the urban ambience and what the representation projections can causein the city's image viewers –that is what the justification of the Clean City Law was all about.

Large state capitals in Brazil, like São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro e Curitiba started a process in the revitalization of the city regarding the use of wall advertisings and signs in the visual environment.Not long after that, other cities, as RibeirãoPreto, Londrina and Osasco, alsojoined the movement and release their versions of the Clean City Law, paying attention to the people's well-being and the rational use of the city spaces by the market.

With the implementation of the new law, the environments refresh themselves and re-display the frontages hidden in the signs of shops. With the withdraw of billboards and totems of identification, the traffic through the pathways acquire new formats and urban use begins to concentrate in the freely image that the city used to express,rather than the images of brands and advertisements that pile up on the blocks: the city transforms itself again, but now rescues its own history amid the image emanation. Empty spaces now form the blank area that produces sense.

This research illustrates how the space undergoes certain changes by the interference of advertising images allocated in the urban ambience of the city of Londrina – Brazil, flexed from their first meaning, which will mislead the perception of the city's residents, and how this is remodeled with the removal of several commercial signs and the establishment of the Clean City Law. Theoretical references include the works of Ferrara (1993, 2000), Canevacci (1997) and Lynch (1999). Photography will act as a methodology of data gathering and analysis.

2. The city image

There is an appraisal that the onlooker of the city involuntarily produces regarding its environment, and he does so by means of representations that vary not only because of his sociocultural background, but also because of the uses and habits he associates with a particular location. Nevertheless, his classifications or ratings are not static; they inevitably change since the city is in a continuous state of flux, so he absorbs that urban experience by means of this daily living and the urban images he conceives.

According to Lynch (1999), the observer selects, organizes and attributes signification to what he sees. Therefore, the city's image varies from each observer, this will be only a framed image of the city as a sort of selection.According to the author, “the city is an overlap of individual images” (Lynch 1999: 51), so mentally,certain areas appearto be expressed in all that is the city. They workasmicroimages that, through customs and habits, will lead to greater significance.

In accordance to Canevacci (1997: 35), “understand the city means to collect fragments.” A plurality of meanings can be found. For the author, the population live the city, and at the same time is lived by the city. Naturally, the observer experiences the urban in its transformations, by consuming it, simultaneously, by the daily experience.

From the moment that a person establishes a contact with the space, it is natural to perform certain meaning processes, in which that environment will characterize and thereby ensure idea to the place. It is vital for a person to build this idea, because it will depend on her to perform the process of localization and identification of the spaces in the city. For Lynch (1999), this process occurs with the establishment of three intelligibility levels: the identity, which will ensure the singleness of an area; the structure, which is the physical and spatial connection of the place; and the meaning, which are the senses and representations that the user of urban spaces guarantees to the environment.

Environmental images, therefore, are products of a bilateral process between the observer and its ambience. However, the “urban image is not tight or rigid, but is caught in a fluid, dynamic and selective process: seizes, and attracts this representation from the individual or collective repertoire” (Ferrara 1993: 71-72, our translation). Over time, the change and maturity of individual repertoire and the modifications that occur in urban areas, the images that have been created, can be reframed and vary several times.

The construction of the environmental image of the city viewer is the result of representations that it is faced daily. These, in turn, are composed of a large polyphony; the results are synesthetic representations of locations, which support the creation of a total representation from that space. The representations come from environmental characteristics, which can be olfactory, tactile, kinetic, among others, but above all visual, since “the mental image we recorded from city focus on a basic requirement: the visual quality” (Ferrara 1993: 252, our translation). These polis sensorial qualities ensure the identity and force of the environment signification. Canevacci, (1997), points out that the city is the place for the sight and that is why “visual communication becomes his featured characteristic. [...] Communication is the journey of difference that contains the meaning of information. Urban communication nettled these differences, by multiplying, coexist and made them get into conflict.”(Canevacci 1997: 43).

From the access of the ambience characteristics, the city viewer will be able to formulate their own image of the city, filling the individual images of representations and moving from simple visual observation of the environment to its significance, in other words, from visually to visibility. According to Ferrara (2002: 105, our translation), “the passage of pure concept to iconic exploration leads to signify reproduction process, that comes from visually to achieve the cognitive dynamics of visibility”. The author advocates the theory that the urban elements extrapolate the simple relation of visual data, obtaining a representation that surpasses the environmental image relations, but obtain a genuine signification, going from visually, that is a mere visual observation, for visibility, becoming a reflection from visual data, which turns into a cognitive flow.

3. Clean City Law

The Law #14,223 from September 26th 2006, the Clean City Law, as it became known, is an initiative for the first time in Brazil in São Paulo, by the mayor Gilberto Kassab. It aims to order the elements of the urban landscape, aiming, among other things, attack the visual pollution and environmental degradation. Consequently, the law preserves the cultural and historical memory of the city and facilitates the access to the features of the urban context, in other words, it seeks to recover certain urban senses that were lost over time.

According to the primer of the Law #14,223/06, the citizens have the right to experience a clean landscape, which guarantees more freedom and security in public areas, ensuring the supremacy of the shared resources over corporate interests. Thus, the Law focuses its efforts on a balance of the elements of the city, creating the visual depollution of the urban landscape and ensuring a better quality of life for environmental users, and to ensure the well-organized management of public spaces, with permission of certain publicities, since there is its regulation and supervision by the city, giving the city a better structured and more welcoming environment.

The main impaired by the Clean City Law was publicity, since there were created new communication standards for urban forms, such as the indicative, informative and commercial advertisements. The new law fetched a wide restructuring imagery of the environment, which saw its commercial discourse printed in advertising images being widely contested.

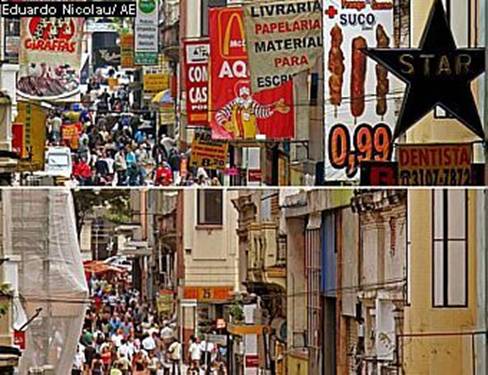

Picture 2: São Paulo City, before and after the Clean City Law.

Source: flanelapaulistana.com. Photography: Eduardo Nicolau.

Inspired bythe São Paulo project, the city of Londrina, Brazil, also enacted their version of the Clean City. The Law #10.966, from July 26th, 2010 stands out as its goal the next point:

Clause 1: constitute objectives of this law the ordering of the landscape and the attendance of environmental comfort needs, with the improving the quality of urban life, by creating new and more restrictive standards, for visible announcements of public places in the territory of the city of Londrina. (LAW #10.996/2010 our translation).

The Londrina’s version is not as soft as the São Paulo’s, in spite of the heavy influence of the latter in the conception of the first. According to the Londrina Law 10.996/2010, posters, signs, and all kinds of display advertising in the downtown area is forbidden, while in the surrounding neighborhoods, such exposure suffers various restrictions. To discuss the new law and its tasks, a Permanent Technical Boardwas defined, which approached several institutions that defended a balance in handling the interests of merchants, external media companies, the town hall and the general population. Through several meetings and intense debate, a consensus was reachedthat led to the placement of advertising in areas of lower flow in Londrina, but with certain limitations, such as size, location in the establishment and distance between two displays of same nature elements, among others. Cases such as advertising vehicles on public roads and their elements such as streets, telephone networks, sewers and energy, roads and telephone booths were banned.

With the conclusion of Law 10.966 / 2010, it can be said that the city's image suffered a major change, and started to connote new meanings when the architecture and the natural image of the environment were recovered, and generated a depollution of the urban landscape of Londrina: there was a visual cleaning in the city, which now did not express itself in the naturalness of the urban fervor, with commercial communications aimed at the mass, but a new “garment” that explores the own territory and its architectural and natural elements.

Picture 3:Sergipe Street (Londrina), before and after the Clean City Law.

Source: Bressan (2011, p. 1226). Photography: Fernanda Grosse Bressan.

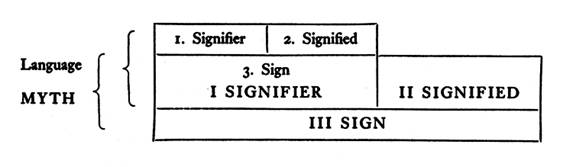

Barthes (2012: 223) has it that “in myth, we find again the tridimensional pattern which I have just described: the signifier, the signified, and the sign. But myth is in a peculiar system, in that it is constructed from a semiological chain which existed before it: it is second-order semiological system (author’s italics).” The sign forming the associative total of a concept and an image in the first system is converted into a “mere” signifier in the second.

We must here recall that the materials of mythical speech (the language itself, photography, painting, posters, rituals, objects, etc.), however different at the start, are reduced to a pure signifying function as soon as they are caught by myth. Myth sees in them the same raw material; their unity is that they all come down to the status of a mere language. Whether it deals with alphabetical or pictorial writing, myth wants to see in them only a sum of signs, a global sign, the final term of a first semiological chain. And it is precisely this final term which will become the first term of the greater system which it builds and of which it is part.(Barthes 2012: 223).

By undoing the typical appropriation by the myth, the Clean City Project operated in reverse: it removed the effects of a sum of signs that replaced the facades in their primary format, thus restoring the first system. In other words, it created an emptiness, an absence capable of expressing more than a mere signifier. The scheme below is a classical illustration of Barthes’s tridimensional pattern:

Source: Barthes (2012, p. 224)

The history of the city of Londrina, the colonization of the northern region of Paraná State, the powerful agricultural background of this same region, the influx of immigrants in various time periods, the architecture brought by coffee wealth (the so-called green gold) and many other associations the visual landscape can allow for, are now recovered. Therefore, a comparative analysis of a before-aftertype, will tend to be instrumental for a more genuine perception of the city. Photography provides a key contribution in this case.

4. The transformation of a visual landscape

The city of Londrina is the fourth largest city in southern Brazil. It has about 500,000 inhabitants and was considered, in the mid-twentieth century, the world capital of coffee. The city had its urban landscape full of signs coming to fill the social imaginary of the population in buildings, houses, shops, large houses dispersed in avenues that lead to the European boulevards, such as Higienopolis Avenue, among others. However, what stood out in Londrina’s urban environment were the interventions from advertisements of various brands and sectors.

In fact, the great intention of the market and industry is to draw the consumer's attention at any cost, without the least concern for the quality of this image. [...] Who do not gain anything from it is the city itself. [...] This situation tightly reflects on the city's image, and in the urban environmental quality of tertiary centers. Visual pollution, orientation trouble, difficulty of movement in the streets and sidewalks, for misuse of the same. (Vargas and Mendes: 2002, our translation)

With the enactment of the Clean City Law, a process of visual depollution of the Londrina’s environment took shape. The law consists in regularizing the situation of advertisings as well as the signs in shops and sale outlets, which are now allowed to occupy only one third of the facade. Through the new legislation, the visual landscape of Londrina suffers a large-scale mutation, in which all its urban context is transformed, in other words, the amalgamation involving the streets, squares, buildings, houses, sidewalks, and other elements that compose the urban scenery are changed in favor of the visual cleaning objectified in the legislation. This change starts in micro plans, through isolated significance of certain buildings, such as stores that redefine their frontage, others that bring the visual characteristics that the buildings had before the establishment of the commerce in that space, among others, going to the macro level, with all the city adapting itself and acquiring a new meaning.

The visual cleaning that the Clean City Law introduced in Londrina emanates new meanings to the space, generating discourses that are naturalized in the environment due to human actions – such as road constructions, the settlement buildings and their architecture – to the imagery exploration of the local flora elements that manifest themselves in the squares, avenue corridors, in front of residences, among many other situations, the people live the city and its elements, and not the commercial appeal of brands anymore.

Thus, it is possible to see that, through the Clean City Law, and the regulation of the publicities aired in the city, it was possible to establish new paradigms in physical and spatial relationship of the environment. The city began to emanate senses that have become transparent over time and were not experienced by its inhabitants, since the ads hide the real significance of the landscape, unseen among the advertisements.

This becomes clear when looking at the same scene into two distinct periods, as in the following example (Picture 4). At first, the space is filled with advertisements, with nameplates of shops and totally focused visual exploration to commercial discourse, while in photography that records the same environment in the post-implementation period of the Clean City Law, is characterized by a rescue of the discourse that is naturalized in the space earlier, with frontages that were under advertisements.

Picture 4: São Paulo Avenue (Londrina), before and after the Clean City Law.

Source: Bressan (2014, p. 90-91). Photography: Fernanda Grosse Bressan.

The presence of advertisements generated new types of representation of the environment, therefore, emanated the brands commercial discourse. However, the imagery renovation of the place made it possible for the deleted discourses on site, to gain strength again and to demonstrate its value. The images (Picture 4) show how the implementation of the Act changed the relationship of space with viewers, as the number of publicities decreased considerably. The imagery renovation of the environment made the Avenue to suffer a deep publicity cleaning, in which shopping facilities had to readjust the new local regulations and a cleaner environment replaced the visual pollution, although popular, but which ensures the experience of a real landscape of the city by the passerby.

The imagery renovation made from a recovery of the original appearance of that urban space allowed the rescue of visual characteristics that the environment had lost slowly over the years. The transformation of the environment generated new meanings after the extraction of the publicities, the place became more enjoyable and less visually polluted.

At the same way, in the Sergipe Street, an important market street in Londrina, the changes are clearly evident:

Picture 5: Sergipe Street (Londrina), before and after the Clean City Law.

Source: Bressan (2014, p 45-49). Photography: Fernanda Grosse Bressan.

The space that previously had a significant number of publicities was substituted by a much clearer view of the environment, ensuring the user of the space to experience the natural urban landscape of the place, without that amount of publicity messages that previously overloaded the space and made that environment, an enhancer of the business/commercial discourse.The directions emanated after the Law deployment ensured the environment the right to issue their real discourse, through its signs, and not those imposed arbitrarily by the commerce and the capitalist system.

By the results obtained with the Clean City Law in Londrina, it is possible to say that the city gained a new guise, its image began to emanate senses that tend to more urban and less commercial meanings. The ability to enhance the urban landscape of the city ensured that the environment could become naturalized effectively, showing its natural and architectural significance, where the city received an ordering of its landscape and generated, in fact, an environmental comfort regarding their visual characteristics.

5. Closing remarks

The city designs senses while generating representations, the daily life of human beings in the urbanity fills it with meanings that will facilitate the City comprehension procedure. In this process, the individual interfere the urban environment by creating their own representations and exploring the city's image through the meanings imposed to it. Similarly, the presence of advertising on pathways, buildings, and commercial elements, makes the discourse of the environment to be changed, gaining meanings related to commercial purpose.

The Clean City Law acts in the urban environment in a similar way, because it makes it acquires new meanings from the removal of publicity signs: the city started to emanate a sense that it is natural of things, of everyday, and not the commercial discourse that publicity gives to the environment. The city began to live more its urban visuality with the everyday experience of architecture, who hid under the gables, windows and billboards.

Picture 6: After the Clean City deployment in Londrina, many shops showed the original architectural design, especially on the Sergipe Street.

Source: www.londrina.odiario.com. Photographs: Divulgation/ACIL. No photographer credits.

The barthesian conception that “myth hides nothing: its function is to distort, not to make disappear (author’s italics)” (Barthes, 2012, p. 231) works as an eye opener, since the natural elements of Londrina were visually revitalized, considering that its uses and habits were made almost invisible – but had not disappeared! Nowadays one can have access to the story on the bricks and tiles of the old buildings of the city. The reordering of the urban image assured the population to experience the elements of the city that were hidden under the commercial discourse of the publicity messages.

It is concluded, therefore, that the reception arising from the publicities that filled the Londrina urban scenario changed the direction of the city's places and, from its imagery renewal, generated a broad redefinition of the visual qualities of Londrina, that were translucent by commercial messages.

References

AGREST, Diana & Mario GANDELSONAS. 2006. Semiotics and Architecture: ideological consumption or theoretical work. In: NESBITT, Kate (eds.). A new agenda for architecture. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify.

BARTHES, Roland. 2012. Mythologies. New York: Hill and Wang.

BRESSAN, Fernanda Grosse. 2012. Portraits of urban transformation: the use of photography as a visual record of the “before” and “after” Clean City Law in Londrina. Londrina, PR: Londrina UniversityState dissertation.

CALVINO, Ítalo. 1990. InvisibleCities. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

CANEVACCI, Massimo. 1997. The city polyphonic. São Paulo: Studio Nobel.

CULLEN, Gordon. 2002. Urban Landscape. Lisboa: Edições 70.

FERRARA, Lucrécia D’Alessio. 1986. The strategy of signs: language, space, urban environment. São Paulo: Perspectiva.

FERRARA, Lucrécia D’Alessio. 2002. Design in spaces. São Paulo: Rosari.

FERRARA, Lucrécia D’Alessio. 1993. Peripheral Look. São Paulo: Edusp.

LONDRINA (PR). Municipal Law#10.966, 26th july 2010. Provides for the ordering of ads that compose the urban landscape of the city of Londrina – CLEAN CITY PROJECT among other provisions.www.londrina.pr.gov.br/dados/images/stories/Storage/ncom/ cidade_limpa/lei_cidade_limpa.pdf. (Last accessed 13 August 2014).

LYNCH, Kevin. 1999. Image of the city. São Paulo: Martins Fontes.

MENDES, Camila Faccioni. 2006. Urban landscape: a rediscovery media. São Paulo: Senac São Paulo.

ORLANDI, Eni de Lourdes Puccinelli (eds). 2001. Crossed city: public way in the urban space. Campinas: Pontes.

ORLANDI, Eni de Lourdes Puccinelli (eds). 2004. City of senses. Campinas: Pontes.

VARGAS, Heliana Comin & Camila Faccioni MENDES. 2002. Visual pollution and urban landscape: who profits from the chaos?http://www.vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquitextos/02.020/816. (Last accessed20August 2014).