REVELIO! A (SOCIO-)SEMIOTIC READING OF THE HARRY POTTER SAGA

University of Applied Arts Vienna, Austria

Abstract

Though it’s already seventeen years that Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone appeared, the first novel of the Harry Potter saga concluded by Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in 2007, the craze about the Boy Wizard has a bit decreased but is by far not over: in 2012 the Leavesden Studio near London (where all eight movies were made) opened as the Warner Bros. Studio Tour London and J.K. Rowling started her interactive website Pottermore; since 2010 fans can visit Hogsmeade and Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry at the Orlando, FL theme park Wizarding World of Harry Potter which has just got a second part depicting Diagon Alley; and in 2016 the first part of a new trilogy dealing with the author of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them will hit the movie theaters all over the world.

It is already seventeen years that Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Rowling 1997) appeared: the first novel of the Harry Potter saga concluded with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in 2007.[1] The craze about the Boy Wizard has decreased slightly, but is by far from over. Books appear in new editions; all the films are constantly aired on television; ever new DVD and Bluray boxes appear on the market; and there are various activities connected to Harry Potter (from conferences to websites) – enough to keep older fans on track and attract ever new fan generations.

Reading the books, watching the movies and buying collectibles is definitely not confined to young adults, the original primary target group, nor is all that done just for fun, as the long list of books and articles analyzing the texts and the phenomenon demonstrates. Authors – and even a few scientists are among them – come from the entire spectrum of the humanities. However, there are so far not too many semiotically oriented papers.

In this essay, I will attempt to read the texts from three different canons (the novels, subsequent writings by J.K. Rowling in print and online, and the movies), from a socio-semiotic perspective inspired by the work of Ferruccio Rossi-Landi. I will focus on the character of magical performance which can be examined in view of his concepts of materiality, signs and bodies. Unfortunately, other questions touching a more comprehensive (socio‑)semiotic analysis can only be briefly mentioned; the same goes for topics obviously related to specific sign systems like runes and divination as well as the strong intertextual and intratextual relations presented in the saga.

1. From one Philosopher’s Stone to three Deathly Hallows: a brief introduction to the Harry Potter universe, the “Potterverse”

There are the seven books (Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, …Chamber of Secrets, …Prisoner of Azkaban, …Goblet of Fire, …Order of the Phoenix, …Half-Blood Prince, …Deathly Hallows; Rowling 2004a–e, 2006, 2008a) published in ever new editions both in the UK and in the US, not to mention the translations appearing in more than 70 languages plus the three smaller books (Quidditch Through the Ages, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and The Tales of Beedle the Bard; Rowling 2001a, 2001b, 2008c) and a sort of prequel of approximately 800 words (Rowling 2008b). There are eight movies (Columbus 2001, 2002, Cuáron 2004, Newell 2005, Yates 2007, 2009, 2010, 2011); and rumor has it that in 2016 the first installment of a new trilogy will be released focusing on the Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and its “author” Newt Scamander. In 2012 Rowling launched the Pottermore website with a chapter by chapter presentation of the books and tons of additional background texts (as of December 2014, the last three chapters of book five plus books six and seven are not yet online).

Since 2010 fans can visit (a reconstruction of the film architecture of) Hogsmeade and the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry at the Florida theme park The Wizarding World of Harry Potter. It has recently opened a Diagon Alley part (Diagon Alley is a famous street in the Harry Potter stories). In July 2014 another theme park opened as part of the Universal Studios Japan in Osaka; a third one in Los Angeles is under construction. The Leavesden Studios near London (where all eight movies were made) opened their sets in 2012 for the Warner Bros. Studio Tour London, and since 2009 a Harry Potter exhibition is touring the world. Last but not least, there is the massive merchandising, both in shops and online, offering e.g. replicas of wands, scarfs in the colors of the four houses, bookmarks, etc. Since December 2012 even in King’s Cross Station there is a Platform 9¾, the train platform where Harry and his cohorts leave from for Hogwarts.

2. A first closer look on the saga from a semiotic view point

There aren’t too many semiotic papers in the strictest sense on the series[2], but a lot has been written in closely related or overlapping areas. First and foremost, there are a number of analyses on the narrative structure. John Granger, perhaps the most important Harry Potter pundit, has published a discussion of the ring composition in each individual book and with regard to the whole series (2010).

Another aspect of the books that has been widely discussed is the overall intertextuality, both in the narrower sense of alluding to other literary texts, and in the broader sense of references to history, culture, and, above all, mythology. J.K. Rowling revived the genre of the English boarding school novel – to name just the most prominent example: Tom Brown’s School Days (Hughes 1857; cf. Granger 2009 ch.3) – and fused it with other genres. On the level of particular writers, scholars have found parallels to both C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. When it comes to cultural and historical references, we may look at actual persons, like Nicolas Flamel, the French medieval alchemist, whom Rowling remodeled to be part of her universe. And there are all the mythical creatures, from basilisks or centaurs to unicorns and werewolves.

Moreover, we find also intratextual relations, like the two stones that figure prominently in the series: the Philosopher’s Stone in the first novel, used to create an Elixir of Life (which “will make the drinker immortal”, Rowling 2004a: 149), and the Resurrection Stone introduced in the final book (Rowling 2008a), which can bring back a shadowy version of dead persons. There are many more examples that can easily be recognized. One of them may even count as part of the above mentioned chiasmic structure. When Harry, Ron and Hermione try to secure the Philosopher’s Stone towards the end of the first book, they are suddenly entangled by a magic plant that almost chokes them:

‘Devil’s Snare, Devil’s Snare … What did Professor Sprout say? It likes the dark and the damp –’ ‘So light a fire!’ Harry choked. ‘Yes – of course – but there’s no wood!’ Hermione cried, wringing her hands. ‘HAVE YOU GONE MAD?’ Ron bellowed. ‘ARE YOU A WITCH OR NOT?’ ‘Oh, right!’ said Hermione, and she whipped out her wand, waved it, muttered something and sent a jet of the same bluebell flames she had used on Snape at the plant […] ‘Yeah,’ said Ron, ‘[…] – “there’s no wood”, honestly.’ (Rowling 2004a: 299)

Close to the end of the Deathly Hallows book, the trio is again harassed by a plant, this time the Whomping Willow that guards the secret entrance to the Shrieking Shack: one has to push a knot on the trunk to immobilize it, as Hermione’s cat Crookshanks did in the Prisoner of Azkaban (Rowlings 2004c: 362). This time Ron doesn’t know what to do:

Panting and gasping Harry slowed down, […] peering through the darkness towards its thick trunk, trying to see the single knot in the bark of the old tree that would paralyse it. Ron and Hermione caught up, Hermione so out of breath she could not speak. ‘How – how’re we going to get in?’ panted Ron. ‘I can – see the place – if we just had – Crookshanks again –’ ‘Crookshanks?’ wheezed Hermione, bent double, clutching her chest. ‘Are you a wizard, or what?’ ‘Oh – right – yeah –’ Ron looked around, then directed his wand at a twig on the ground and said, ‘Wingardium Leviosa!’ The twig flew up from the ground, […]. It jabbed at a place near the roots and at once, the writhing tree became still. (Rowling 2008a: 713–714)

Socio-semiotic aspects of the saga focus, of course, on the societal make-up of the wizarding world and the political situation there. In this context, a lot has been said on the stratification of the society, including the position of non-human magical beings like the house-elves, or on the increasing rigor ending in the final installment in a fascist system.

Another topic would be the organization of the school community and the rituals that structure the year at Hogwarts. One of them is the start-of-term banquet with delicious food, preceded by allocating the first-year students to one of the four houses (Gryffindor, Hufflepuff, Ravenclaw, and Slytherin). However, contrary to an ordinary school, in Hogwarts this task is carried out by the Sorting Hat who reads the mind and personality of the child with regard to the characteristics related to the four houses. Among the other festivities in Hogwarts (and in wizarding families in general) we find Halloween, and Christmas at Hogwarts is celebrated with those students that stay in the castle over the holidays. In both cases, all well known elements and decorations are present, except maybe that the wizard crackers, i.e. the magic version of Christmas crackers, sometimes contain “a rear-admiral’s hat and several live, white mice” (Rowling 2004a: 220).

The skill of mind reading is not confined to the Sorting Hat: among wizards the respective technique is called Legilimancy. However, there are still more decoding processes present in the series. At least three practices described in the novels are akin to interpretive reading: one is divination in its various forms, from stargazing, as done by the centaurs, to the methods Professor Trelawney is teaching: palmistry; and seeing the future in tea leaves or by looking into a crystal ball. Hermione, who considers divination to be “very woolly” (Rowling 2004c: 122), likes other courses better: Arithmancy, a form of divination based on numbers, and translating texts written in ancient runes.

3. Magical (sign) processes

“Revelio” – the first word in the title of this essay refers to a spell, one of the major magic processes we encounter in the written and filmic texts. Casting spells is a typical topos in stories about witchcraft. However, spells in the Harry Potter saga have specific features that can be discussed in terms of the semiotic theory developed by the Italian semiotician and philosopher Ferruccio Rossi-Landi. The way Rowling meticulously describes the procedures and the effects presupposes that magic processes in general and spells in particular have always had both semiosic and material qualities simultaneously.

In the middle of the first chapter of the Philosopher’s Stone (“The Boy Who Lived”), we are confronted for the first time with magic when Dumbledore arrives at Privet Drive in Little Whinging, Surrey. Already since early morning a strange cat is sitting on a wall:

For some reason, the sight of the cat seemed to amuse him [Dumbledore]. He chuckled and muttered, ‘I should have known.’ He had found what he was looking for in his inside pocket. It seemed to be a silver cigarette lighter. He flicked it open, held it up in the air and clicked it. The nearest street lamp went out with a little pop. He clicked it again – the next lamp flickered into darkness. (Rowling 2004a: 15)

In the film version of the scene, the lights are actually whooshing from the lamps into the device. But there is even more in this scene, though we are allowed a closer look at the very process only later on. Dumbledore

set off down the street towards number four, where he sat down on the wall next to the cat. He didn’t look at it, but after a moment he spoke to it. ‘Fancy seeing you here, Professor McGonagall.’ He turned to smile at the tabby, but it had gone. Instead he was smiling at a rather severe-looking woman who was wearing square glasses exactly the shape of the markings the cat had had around its eyes. (Rowling 2004a: 16)

Explanation: Minerva McGonagall is an Animagus: she can change into an animal at will. In the movie Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Columbus 2001), we can watch how she does it. When Ron and Harry are late for their very first Transfiguration class, the desk is empty except for a cat. Satisfied that they escaped a reprimand, Ron panted, “Whew! We made it! Can you imagine the look on McGonagall’s face if we were late?” A split second later he realized how wrong he was: with an elegant leap the cat turned instantly into Professor McGonagall.[3]

4. Rossi-Landi on “Signs and Bodies”

These last two examples showed two different magic processes which both involved very material effects. Let us now consult Rossi-Landi’s semiotic theories. Forty years ago, Ferruccio Rossi-Landi wrote a paper titled “Signs and Bodies”, which he presented at the first Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies in Milan in June 1974. Later on the text appeared in the proceedings, edited by Chatman, Eco and Klinkenberg (Rossi-Landi 1979; 1992b).

In this relatively short text he proceeds from five propositions concerning the relation between signs and bodies, and since the paper is not widely known, I will present some central quotes:

A, All signs are bodies; B, Not all bodies are signs; C, All bodies can be signs. And D, Signs are not bodies; E, All bodies are signs. (Rossi-Landi 1992b: 271)

Rossi-Landi formulates his main working hypothesis as such: whereas D and E belong to idealistic semiotics, the propositions A to C form “the basic model of materialistic semiotics” (Rossi-Landi 1992b: 272). He continues by further discussing the intricate relation:

According to this hypothesis, materialistic semiotics starts with bodies, and by realizing that bodies can be or not be signs, comes to consider signs as a subclass of bodies-in-general (Rossi-Landi 1992b: 272).

Rossi-Landi also makes a remark here that is of importance for our understanding of particular sign and material operations:

As speakers of at least one natural language, we all distinguish between “signs” and “bodies” to some extent. […] All we need to add at this stage is that ‘bodies’ in the widest sense must refer to all conditions of matter, including energy, and that ‘signs’ stands for semiosis in general. (Rossi-Landi 1992b: 272; my emphasis)

Later in the text Rossi-Landi argues against “Semiotical Panlogism”:

Bodies, and not signs only, are the world’s furniture. Bodies are to be met both outside of signs and within signs themselves. Interpreters are bodies with needs, desires, illnesses, etc., and not only bodies capable of using signs. […] If you kill a man, you kill a man, and not only an interpreter. Social life, while being entirely covered by sign systems up to the point that without signs it wouldn’t be social and, possibly, it wouldn't even be life, consists also of something else. (Rossi-Landi 1992b: 275)

Rossi-Landi concludes by asking for several lines of investigation that he actually carried out himself over the next decade, starting with his “Theory of Sign Residues” in which he further elaborates the specific materiality involved in semiosis.[4] Without conducting an in-depth discussion of his semiotic models, I’d nevertheless like to mention at least one aspect that is related to the matter–sign relation. The most comprehensive concept in Rossi-Landian socio-semiotics is Social Reproduction – “the sum total of all processes by means of which a community or society survives, grows bigger, or, at least, continues to exist.” (Rossi-Landi 1985: 175)

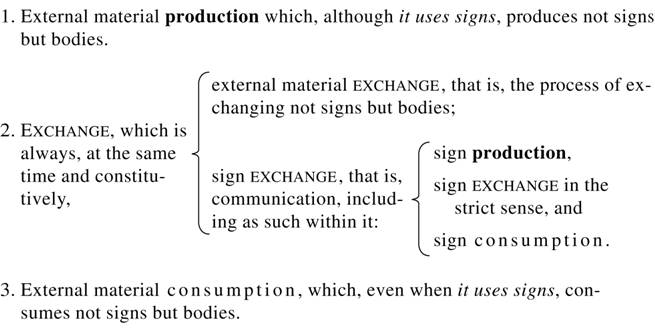

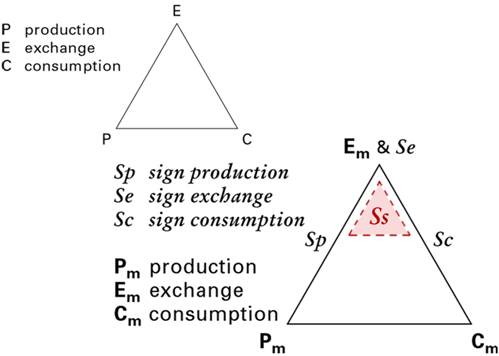

Viewed in their totality, there are several different processes that act within social reproduction. The basic one, summarized in the Schema of Social Reproduction (Rossi-Landi 1975: 65; 1985: 38), is the cycle of production – exchange – consumption, composed of “three indissolubly correlated moments” which social reproduction “always comprehends in a constitutive way” (Rossi-Landi 1975: 65). The moment of exchange, conceived in a twofold way, is at the very center of the schema. It is simultaneously both external material exchange, and sign exchange, which is in itself the reduplication of the entire cycle and comprehends again “three indissolubly correlated moments”: sign production, sign exchange and sign consumption.

When switching from the verbalized schema (which already includes a spatial presentation of the internal relations) to a diagrammatic form, the most adequate configuration seems to be the triad. Proceeding from the basic triad P–E–C, the two different moments of exchange can be visualized by reduplicating the triad of sign production, sign exchange and sign consumption within the major point of exchange.

5. The semiotics of spells and other magic practices

Analyzing magical processes as described and depicted in the Harry Potter saga in the light of these concepts reveals them to be excellent examples of the sign-body duality. Magical sign processes are always simultaneously and in a constitutive way material and sign processes. The semiosic elements and the material elements are indissolubly correlated.

Sign production in the process of magic is always and at the same time the production of something material in the strict sense, hence the semiotics of Rossi-Landi is the appropriate background theory. Magical processes are part and parcel of the Potterverse. Though, according to Rowling, the ability to do magic is innate; it is not confined to wizard/witch families and can occur also in “Muggle-born” children (i.e. of non-magical parents).

Since spells are definitely the central magic procedures, my examples come from this domain. In general, a spell consists of an incantation (vocalized or non-verbal, that is, only mentally represented) mostly together with a specific movement of the wand; the intent to cast the spell;[5] and the effect/result. (Maybe it’s too far-fetched, but this triadic structure of spells seems to be akin to certain models of signs or semioses.) Based on the books, we find several classifications of spells, like transfiguration, charm, jinx, hex or curse (cf. http://harrypotter.wikia.com/wiki/Spell). For our purpose I propose another simplified way of arranging spells, or acts of magic in general, into two major categories, differentiating between:

(i) the materiality of the magic process; and

(ii) the materiality of the result.

The first category comprises both the corporeal quality of the process itself, and whatever emanates from the wand when a spell is cast. The second category touches the actual changes of the target of the act of magic. Beginning with the second category, we have already witnessed, in Ron Weasley’s words (Columbus 2001) one “bloody brilliant” act of magic, the auto-transfiguration of an Animagus. Transfiguration is one of the major subjects taught at Hogwarts, at one point in the Chamber of Secrets movie we are allowed a closer look at the spell and wand movement involved when Professor McGonagall demonstrates how an animal is turned into a water goblet (Columbus 2002).[6]

Even if they are not capable of changing into an animal, wizards and witches can disguise themselves as objects, as is the case with Horace Slughorn early in the Half-Blood Prince where he appears to be an armchair. Yet he can’t fool Dumbledore:

And without warning, Dumbledore swooped, plunging the tip of his wand into the seat of the overstuffed armchair, which yelled, ‘Ouch!’ ‘Good evening, Horace,’ said Dumbledore, straightening up again. Harry’s jaw dropped. Where a split second before there had been an armchair, there now crouched an enormously fat, bald old man who was massaging his lower belly and squinting up at Dumbledore with an aggrieved and watery eye. ‘There was no need to stick the wand in that hard,’ he said gruffly, clambering to his feet. ‘It hurt.’ (Rowling 2006: 81)

In the wizarding world even memories appear in material form as silvery-white gossamer-like threads. Just like files from a hard disk, they can be extracted from the brain, stored away in vials, and later on, be poured into the Pensieve and revisited:

Then, very slowly, Slughorn put his hand in his pocket and pulled out his wand. He put his other hand inside his cloak and took out a small, empty bottle. Still looking into Harry’s eyes, Slughorn touched the tip of his wand to his temple and withdrew it, so that a long, silver thread of memory came away too, clinging to the wand-tip. Longer and longer the memory stretched until it broke and swung, silvery bright, from the wand. Slughorn lowered it into the bottle where it coiled, then spread, swirling like gas. He corked the bottle with a trembling hand and then passed it across the table to Harry. (Rowling 2006: 580)

Now to the first category. The books are full of vivid descriptions of the corporeal aspect of spells. You “aim” and “shoot” a spell at somebody; if you do not “dodge” or “leap aside” to avoid the spell, it will “hit” you – and you will experience or even suffer the result: from a mere tickle (Rictusempra) to confusion (Confundo); losing the own wand (Expelliarmus); being unable to move (Impedimenta or Petrificus Totalus); being stunned and unconscious (Stupefy); feeling unbearable pain (the Cruciatus curse); or in the worst case: dying (Avada Kedavra).

The spell can also result in more or less massive (temporary or permanent) visible and tangible changes of the body or the targeted object: objects can be raised into the air (Wingardium Leviosa); caused to explode in flames (Confringo); made bigger (Engorgio) or smaller (Reducio); or made to vanish completely (Evanesco). Among the spells causing body alterations we find: Furnunculus (to produce boils and pimples); Episkey (to heal minor injuries like a broken toe or nose); a vomiting slugs hex; a stinging hex which swells the face beyond recognition; and the Sectumsempra curse that slashes a person, resulting in deep, mostly incurable wounds (only Snape knows an incantation to heal them; cf. Rowling 2006: 618). However, since the casted spell itself has a corporeal quality, you can “block”, “repel” or “deflect” a spell. It can “rebound” on a wall and “bounce back” or hit an object and smash it.

The tip is the most important part of the wand, as many different objects can emerge from or shoot out of it: Lumos lights the tip of the wand; Aguamenti produces a jet of water (Rowling 2004d: 394; 2006: 714); when two persons make an Unbreakable Vow, a “thin tongue of brilliant flame” shoots from the wand of the person casting the spell, “making a fine, glowing chain” around the hands of those engaged in the vow (Rowling 2006: 49). The wand can also be used for decoration purposes: “Hermione made purple and gold streamers erupt from the end of her wand and drape themselves artistically over the trees and bushes” (Rowling 2008a: 133); when the incantation Orchideous is spoken, a “bunch of flowers burst from the wand tip” (Rowling 2004d: 338); and both in the last book and in the movie, Hermione conjures a wreath of Christmas roses when they visit the grave of Harry’s parents (Rowling 2008a: 365).[7] The tip of the wand can be used in a less amiable way, as with the Incarcerous spell: ropes fly out of the wand and tie up the targeted person (e.g. Rowling 2004e: 826; 2008a: 187).

In one particular case, something extremely powerful erupts from the tip: the Patronus of the witch or wizard who casts the spell. Everyone has his or her own unique Patronus, a silvery shining guardian-being who shields a person against Dementors. Harry learns how to produce a Patronus in his private lessons with Remus Lupin in the Prisoner of Azkaban, and later on he teaches his friends in the Order of the Phoenix. The most common effect, however, is a flash or jet of light shooting from the wand. When in the first book, Harry finally finds his own, personal wand, “a stream of red and gold sparks shot from the end like a firework” (Rowling 2004a: 96). The light jets come in different colors for different spells: silver (Rictusempra), red (Expelliarmus or Stupefy), or, when the Killing Curse is performed, green.

Having a corporeal quality themselves, spells can collide in mid-air, which happens several times throughout the series. The most spectacular collision of light jets, however, appears in the final battle between Voldemort and Harry when they both cast their respective spells:

‘Avada Kedavra!’ ‘Expelliarmus!’ The bang was like a cannon-blast and the golden flames that erupted between them, at the dead centre of the circle they had been treading, marked the point where the spells collided. Harry saw Voldemort’s green jet meet his own spell, saw the Elder Wand fly high […]. And Harry, with the unerring skill of the Seeker, caught the wand in his free hand as Voldemort fell backwards, arms splayed, the slit pupils of the scarlet eyes rolling upwards. Tom Riddle hit the floor with a mundane finality, his body feeble and shrunken, the white hands empty, the snake-like face vacant and unknowing. Voldemort was dead, killed by his own rebounding curse, and Harry stood with two wands in his hand, staring down at his enemy’s shell. (Rowling 2008a: 814–815)

6. Semio-magic epilogue

Those who know Rossi-Landian semiotics may consider it odd to refer to a materialist sign theory to talk about a children’s book dealing with the wizarding world. However, for the purpose of recalling Rossi-Landi’s discussion of the interrelation between signs and bodies, I hope that choosing such well-known and loved literature to analyze has helped to raise awareness of a topic vital to semiotics. The material aspects of sign processes are often neglected, but have to be taken into account, in order to avoid the idealistic trap. Why not do so with the help of literary examples? After all – to end with one of the last sentences spoken by the great wizard Dumbledore in the film Harry Potter and Deathly Hallows Part 2 (Yates 2011) – “Words are, in my not so humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of magic.”

References

BEHR, Kate. 2008. Philosopher’s Stone to Resurrection Stone: Narrative Transformations and Intersecting Cultures across the Harry Potter Series. In: Heilman 2008, 257–271.

COLUMBUS, Chris. 2001. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s [Sorcerer’s] Stone [film]. USA: Warner Bros.

COLUMBUS, Chris. 2002. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets [film]. USA: Warner Bros.

CUARÓN, Alfonso. 2004. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban [film]. USA: Warner Bros.

ELLIS, Molly. 2012. Legitimate Exchange: Legitimacy through Reciprocity in Harry Potter. In: Haworth, Karen, Jason Hogue & Leonard G. Sbrocchi (eds.). 2012. Semiotics 2011. The Semiotics of Worldviews. Ottawa & New York: Legas Publ., 373–386.

ESTEP, Christina. 2012. Dueling Triangles: Power and Authority Struggles within the Wizarding World”. In: Haworth, Karen, Jason Hogue & Leonard G. Sbrocchi (eds.) (2012). Semiotics 2011. The Semiotics of Worldviews. Ottawa & New York: Legas Publ., 364–372.

GRANGER, John. 2008a. The Deathly Hallows Lectures: The Hogwarts Professor Explains the Final Harry’s Adventure. Allentown: Zossima Press.

GRANGER, John. 2008b. How Harry Cast His Spell: The Meaning Behind the Mania for J. K. Rowling’s Bestselling Books. Carol Stream: Tyndale House Publishers.

GRANGER, John. 2009. Harry Potter's Bookshelf: The Great Books Behind the Hogwarts Adventure. New York: Berkley Books.

GRANGER, John. 2010. The Hogwarts Saga as Ring Composition and Ring Cycle. The Magical Structure and Transcendent Meaning of the Hogwarts Saga. Cleveland NY: Unlocking Press.

HEILMAN, Elizabeth E. (ed.). 2008. Critical Perspectives on Harry Potter. New York: Routledge.

HUGHES, Thomas. 1857. Tom Brown’s School Days. London: Macmillan.

NEWELL, Mike. 2005. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire [film]. USA: Warner Bros.

REAGIN, Nancy R. (ed.). 2011. Harry Potter and History (= Wiley Pop Culture and History Series). Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

ROSSI-LANDI, Ferruccio. 1979a. Ideas for a manifesto of materialistic semiotics. KODIKAS/Code 2: 121–123.

ROSSI-LANDI, Ferruccio. 1979b. Signs and bodies. In: Chatman, Seymour, Umberto Eco et Jean-Marie Klinkenberg (eds.). A Semiotic Landscape. Proceedings of the First Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies, Milan, June 1974. The Hague: Mouton, 356–359.

ROSSI-LANDI, Ferruccio. 1979c. Towards a Theory of Sign Residues. Versus 23: 15–32.

ROSSI-LANDI, Ferruccio. 1988. Il segno e i suoi residui. In: Ponzio 1988, 263–289 [= transcript of a lecture given at the Università degli studi di Bari on 19 April 1985, edited by Angela Biancofiore after a tape recording.

ROSSI-LANDI, Ferruccio. 1992a. Between Signs and Non-Signs. Ed. Susan Petrilli (= Critical Theory 10). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

ROSSI-LANDI, Ferruccio. 1992b. Signs and bodies. In: Rossi-Landi, Ferruccio (1992a). Between Signs and Non-Signs. Ed. Susan Petrilli (= Critical Theory 10). Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 271–276.

ROSSI-LANDI, Ferruccio. 1992c. Towards a Theory of Sign Residues. In: Rossi-Landi, Ferruccio (1992a), Between Signs and Non-Signs. Ed. Susan Petrilli (= Critical Theory 10). Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 281–299.

ROWLING, J.K. [& Newt Scamander]. 2001a. Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. London: Bloomsbury & New York NY: Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic.

ROWLING, J.K. [& Kennilworth Whisp]. 2001b. Quidditch Through the Ages. London: Bloomsbury & New York NY: Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic.

ROWLING, J.K. 2004a. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. London: Bloomsbury.

ROWLING, J.K. 2004b. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. London: Bloomsbury.

ROWLING, J.K. 2004c. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. London: Bloomsbury.

ROWLING, J.K. 2004d. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. London: Bloomsbury

ROWLING, J.K. 2004e. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. London: Bloomsbury.

ROWLING, J.K. 2006. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. London: Bloomsbury.

ROWLING, J.K. 2008a. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. London: Bloomsbury.

ROWLING, J.K. 2008b. The Harry Potter Prequel. Waterstones’ Charity Auction; Web:http://web.archive.org/web/20101222170726/http://copiedtext.blogspot.com/2010/10/harry-potter-prequel-by-jk-rowling-2008.html; http://www.snitchseeker.com/gallery/displayimage.php?album=89&pos=7; http://www.snitchseeker.com/gallery/displayimage.php?album=89&pos=8 [visited 2014-12-15].

ROWLING, J.K. 2008c. The Tales of Beedle the Bard. London: Children’s High Level Group & Bloomsbury.

ROWLING, J.K. 2012–. Pottermore. http://www.pottermore.com.

ST. DENNIS, Elijah Samuel. 2012. Harry Potter and the Making of Myth: A Look at the Harry Potter Franchise as Myth and its Meaning. In: Haworth, Karen, Jason Hogue & Leonard G. Sbrocchi (eds.). 2012. Semiotics 2011. The Semiotics of Worldviews. Ottawa & New York: Legas Publ., 387–393.

VANDER ARK, Steve. 2009. The Lexicon: An Unauthorized Guide to Harry Potter Fiction and Related Materials: A Passage of Ghosts. Muskegon MI: RDR Books & online:

VOSTOK et al. 2005–. Harry Potter Wiki. http://harrypotter.wikia.com/wiki/.

WILLIAMSON Huber, Margaret. 2012. Analogical Classification in the Wizarding World. In: Haworth, Karen, Jason Hogue & Leonard G. Sbrocchi (eds.). 2012. Semiotics 2011. The Semiotics of Worldviews. Ottawa & New York: Legas Publ., 350–363.

YATES, David. 2007. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix [film]. USA: Warner Bros.

YATES, David. 2009. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince [film]. USA: Warner Bros.

YATES, David. 2010. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 [film]. USA: Warner Bros.

YATES, David. 2011. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 [film]. USA: Warner Bros.

[1] A brief summary of the saga: Surrey, England in the early 1990s. An eleven-year-old orphaned boy, raised by his maternal aunt and her husband, is told that he is a wizard and will receive his education at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, somewhere up north in Scotland. Already in his first year he is confronted by Voldemort, the wizard who has murdered Harry’s parents, but failed to kill the little boy. Over the next years the boy and his friends, in particular Ron and Hermione, continue to fight the Dark Lord, until, at the end of the seventh and last book, Harry is finally victorious and during a duel Voldemort dies of his own Killing Curse.

[2] In the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Semiotic Society of America, a panel dealt with the topic “Factual Fiction: A Structural Analysis of Harry Potter”. The four papers presented appeared also in the proceedings: Ellis 2012, Estep 2012, St. Dennis 2012, Williamson 2012.

[3] In the novel, McGonagall demonstrates transfiguration by changing “her desk into a pig and back again.” (Rowling 2004a: 147)

[4] In his last lecture in Bari in April 1985, Rossi-Landi came back once more to the topic of signs and their residues (Rossi-Landi 1988).

[5] After Bellatrix has killed his godfather Sirius Black in the Order of the Phoenix, Harry tries to cast a Cruciatus curse on Bellatrix that fails to produce the proper effect. She claims to know why: “You need to mean them, Potter! You need to really want to cause pain – to enjoy it” (Rowling 2004e: 891).

[6] In the book, the children have to turn a beetle into a button. (Rowling 2004b: 105)

[7] However, when it comes to conjuring, the items a witch or a wizard can produce are somehow limited by Gamp’s Law of Elemental Transfiguration which contains five Principal Exceptions, such as food (Rowling 2008a: 325) and, as is evident by the existence of the vaults at Gringott’s (the bank in the wizarding world), money.