TOWARDS A QUANTITATIVE VISUAL SEMIOTICS?

Panteion University, Athens, Greece

Abstract

Visual Semiotics, as is the case with most of Visual Studies so far, have not found yet a sound and methodologically rigorous equilibrium between ‘visual’ and ‘semiotics’. Instead, following existing examples, they scrutinize visuality, the gaze and other similar objects of inquiry, or work on visual grammar and syntax. In all cases, they deal mostly with meta-language about images than with images themselves. They deal mostly with words used to describe the visual (either produced by the researcher or by others) than with the visual itself.

In this paper, I am to propose the use of existing software tools in order to achieve research in quantifiable signifiers in visual images, and their manipulation towards a quantitative semiotics. Concepts like ‘entropy’, ‘hue’, ‘saturation’, ‘mean RGB’ etc. are the computed signifiers which are actually visible but so far visual researchers were unable to tap upon. Illustration of the method will be provided by my current research.

1. Introduction

Decade after decade, the number of photos produced per year is multiplied, reaching the incredible amount of 380 billion in 2012. According to Schwartz (2012) 3.8 trillion photos had been taken from the invention of the camera till 2012. This number is amazing (though it may be a mere guess), and still leaves beyond contemplation video and all forms of “moving” images, as well as multimedia products, software interfaces, computer games, to name but a few types of modern visual data. Almost two centuries since the invention of camera, five centuries of print images, millennia of hand-drawn pictures, and two decades of digital media, the visual realm is now vast enough to be considered under the name of big data.

On the other hand, it looks like visual semiotics is more comfortable with less data. Actually, one or few images are considered enough. Half a century after the famous essay by Roland Barthes, “Rhetoric of the Image”, we still “start by making it considerably easier for ourselves” (Barthes 1977: 33). We are thus replicating, more or less, what is already known, at least methodologically. But the advent of big visual data readily available, combined with the epistemological shift in Digital Humanities, plus the opportunity to use software appropriate for the analysis of visual images, compose a new framework for the exercise of visual semiotics –namely, a quantitative visual semiotics.

In the following paragraphs I will take as an example the semiotic analysis of music album covers, to demonstrate a still highly experimental approach to such a version of semiotics. My approach takes into account, as a distant precursor, the work of Groupe μ in Traité du signe visuel (1992).

2. The analysis of music album covers

Man, if you want to see where the world’s been,just look through some old album covers

Patty Smith

Jones and Sorger remind the reader that “when Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols proclaimed, ‘if people bought the records for the music, this thing would have died a death long ago’, he illustrated the importance and power people place on ‘the look of music’” (Jones and Sorger 1999: 68). As Toivanen points out: “The album cover art is an essential part of the vinyl record use experience. The record is not just for listening, but to be held and looked at, as well. ‘The artwork is a continuation to the soundscape of the album’” (Toivanen 2014: 34).

Music disc covers of any format (vinyl or CD) are cultural artifacts of a specific status. As cultural artifacts, “images converge into a single scope: That of transmitting old ideas in order to awaken new perceptions and the desire to consume” (Fiore and Contani 2014: 40). While, as Patti Smith said once: “Man, if you want to see where the world’s been, just look through some old album covers” (quoted in Jones and Sorger 1999: 70). Existing literature on album artwork (cf. Robertson 2007; Bestley 2014; Blue 2011; Grant 2001; Jones and Sorger 1999) shows that it is connected to the cultural and political values of the social environment within which they were produced and consumed (Chapman 2012; Lowey and Prince 2014; Shaw 2014; Hickam and Wallach 2011; Karjalainen and Ainamo 2011; Karjalainen, Laaksonen, and Ainamo 2009; Alleyne 2014; Inglis 2001), or even the global environment of the last two decades with it globalizing impact on both visuals and values.

Album art has been connected to LP and its large 12-inch format (Jones and Sorger 1999: 70; Bartmanski and Woodward 2013: 7), so that its replacement with the much smaller CD cover “has led many to lament the decline, even the disappearance of album art” (Inglis 2001: 83). It is intriguing to find that more than a decade later, despite the familiarity of music CDs, the same stance is held (Toivanen 2014: 39).

Androutsopoulos and Scholz suggest that:

Every vinyl or CD record is a semiotically complex textual unit. It consists of the sound material of the CD itself and the verbal and visual material of the CD cover and booklet, which includes pictures, acknowledgments, and various promotional texts. While record cover and booklet are certainly peripheral in terms of artistic value, they are nevertheless quite important for the self-presentation of the artists. (Androutsopoulos and Scholz 2003: 469; cf. Fiore and Contani 2014: 38)

Album covers are multifunctional visual cultural artifacts, since they:

· “Ensure the protection of the recording they contain” (Inglis 2001: 83; Jones and Sorger 1999: 68).

· They serve as an advertisement (Jones and Sorger 1999: 68). They or their artwork are used in posters, digital or print advertisements. In being a sort of advertisement by themselves, “they reflect the conventions of other media forms, notably the news headline and/or lead, which act as an enticement to the reader to continue reading; and the magazine advertisement or television commercial, which similarly seek to attract and retain the consumer’s attention” (Inglis 2001: 84).

· They are “an accompaniment to the music (…) an integral component of the listening which assists and expands the musical experience” (Inglis 2001: 84). Inglis mentions that the listener may wish to refer to the artwork of the cover during listening to the music, or even read or sing the lyrics provided in the sleeve. There are other ways in accompaniment as well: the artwork may represent the ‘myth’ or the ‘mythological narrative of those involved in the production of the music (the composer, the songwriter, the singer, the band etc.), participating in the production or reproduction of their identity. As Tuomas Holopainen said, with the visual design “we try to create our own Nightwish universe, imagination land, own Nightwish mythology” (quoted in Karjalainen and Ainamo 2011: 31). Another good example offers the “non-representational and abstract album artwork” of Autechre, that complements their secrecy and mystification of their way of doing music (Brett 2015: 9). Another way to put this connection between cover artwork and the music in a larger totality, is the work of artists and studios like Hipgnosis, the studio “effectively translating sonic experiences into still images and accelerating the rock album cover’s development” (Alleyne 2014: 251). Finally, and against the grain of most of mainstream rock covers, the punk covers, “lowbrow, offensive, and easily reproducible on a limited budget” (Acock 2014), duplicate the ideological premises and visualize the cultural directions of punk.

· It is a way to engrave the authority of the ‘label’ (the company) upon its products, inscribing visual elements of its brand on it. According to Pat Dolan in 1940s, “each album should reflect the quality of the Columbia name” (Schmitz in Jones and Sorger 1999: 72).

· The cover has an aesthetic value. “The LP format’s material packaging is relevant for understanding its reported aura” (Bartmanski and Woodward 2013: 6). For example, Inglis mentions that the Beatles’ “album covers themselves have been seen as groundbreaking in their visual and aesthetic properties, have been congratulated for their innovative and imaginative designs, have been credited with providing an early impetus for the expansion of the graphic design industry into the imagery of popular music” (Inglis 2001: 83).

· The cover is a way to approach and experience the work of music. “Cover designs depict what the product means, not what it physically is” (Alleyne 2014: 252), and thus it offers a key to its interpretation by the audience, even if this is not an ‘open’ work. On the other hand, in Brazilian hip-hop the meaning resides in an “attitude” which “is essentially linked to the representation of ‘reality’ and more specifically working-class daily life in Brazil’s impoverished suburbs” (Pardue 2005: 61), and this representation happens visually on the cd covers. According to Pardue, “Hip-hoppers implicitly make correlations between the technologies of image manipulation that comprise the appearance of the CDs and their perspectives on ‘reality’” (Pardue 2005: 62; cf. Pardue 2010: 50). The same holds for the metal scene: “An essential part of the attraction of metal music is not only how it sounds but also how metal looks. Album covers, dressing, stage constructions, posing in photos, facial expression, postures, spectacular shock effects, and small details telling about the extremely precise aesthetics of the sub-culture constitute the visual code system of metal” (Karjalainen and Ainamo 2011: 31).

· “There is an important sense in which an album sleeve can be seen as a commodity in its own right” (Inglis 2001: 84). As such, the cover is a collectible cultural artifact, like many other mass culture products like posters, or photographs (cf. Fullerton and Rarey 2012). Jones and Sorger realize that “LP album covers have not yet lost their cultural status for designers and consumers alike” (Jones and Sorger 1999: 70).

· The cover is a means of communication between the artist(s), the illustrator/designer, and the fan base. In this function, Fiore and Contani indicate that heavy metal album designers utilize “excessively strong images (…); to this end they need the grotesque as a leitmotif for an efficient dialog among all the factors in play” (Fiore and Contani 2014: 39). The authors follow Goulart and suggest that “It is (…) the images and illustrations that the authors (or artists) direct in the function of interlocutor to the social audience or consumer market of heavy metal recordings, t-shirts and videos” (Fiore and Contani 2014: 40).

· The cover is a means of visualizing identity, not only of the artist(s) or band, but also of a sought identity (be it a group, ethnic or local identity) (cf. Weston 2011).

· Finally, the cover artwork may become a sign of fandom, as exemplified in its social media use, or in mashup videos in Youtube.

Album covers are conceived as “visual signposts” of their era (Evans in Inglis 2001: 85). They allow for “a textual analysis yielding rich insights into the ways in which they invite or allow the consumer to decipher them” (Inglis 2001: 85).

From a semiotic point of view “record covers […] convey meaning through all of the semiotic resources of which they are composed: language, typography, images, and layout” (Androutsopoulos and Scholz 2003: 469), and they therefore require a multimodal analysis. Such an analysis requires a strict selection of one or a few covers, since it will either repeat itself or delve into minutiae without being able to provide the wider image. It is no surprising, then, that Androutsopoulos and Scholz analyze only one cover, as “a particularly suitable example” (Androutsopoulos and Scholz 2003: 469); Inglis analyzes only 12 of the “hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Beatles album covers in existence” (Inglis 2001: 84); Shaw is limiting her analysis to four covers from a series of 51 CDs (Shaw 2014: 37–38). Androutsopoulos and Scholz declare: “this is by no means a representative cover for European rap records in general, it does provide an excellent illustration of how a ‘local’ instantiation of the ‘global’ genre is visually encoded” (Androutsopoulos and Scholz 2003: 470). It is clear then, that the selection is not based upon any idea of sampling. It is rather based upon the scholar’s convenience.

3. Methodology

In my research, the focus is cultural dynamics. In short, I am interested in the way cultural artifacts incorporate signs of cultural trends, values, ideas related to a dynamic and changing environment. I am also interested in the ways such artifacts change in time according to this changing environment. Instead of analyzing some dozens of visual images, I attempt to look at 24,066 images covering a certain area of cultural production during half a century. I use as my sample the cover artwork of all the albums produced in Greece since 1960. Existing bibliography (Dragoumanos 2007) shows a prolific production of approx. 28,000 albums. It is impossible to analyze such an amount of visual data the traditional way. Here, as Manovich put it, software takes command (2013).

Software can extract tens or even hundreds of measures for each image, which can then be analyzed in many ways. In the examples of this paper I used an open source program (ImageJ) as well as macros created by the Software Studies Initiative and distributed under a GNU license at their website.[1]

Existing software allows, for example, measuring entropy. For software mechanics entropy “is a measure of the degree of randomness in the image” (Thum 1984: 203), “an intuitive understanding of information entropy relates to the amount of uncertainty about an event associated with a given probability distribution. The entropy can serve as a measure of ‘disorder’. As the level of disorder rises, entropy increases and events are less predictable” (Sonka, Hlavac, and Boyle 2008: 25). Thus, “the higher the entropy, the more complex the image” (Marques 2011: 466).

On a more semiotic ground, the balance between order and fragmentation (i.e. entropy) “is about the degree of coherence of the world” (Groupe μ 1992: 35). On the other hand, it is clear that the meaning of entropy in our software is quite different from the teleological use of it by Arnheim (1971), and criticized by Groupe μ. We could expect that when the “coherence of the world” is less valued, when the world appears to be incoherent or fragmented, when personality is more important than collectivity, then visual representations would be more entropic. So, as our society proceeds towards postmodernism, we should expect visual cultural representations to become more entropic.

On a sociological level, this would be compatible with R. Inglehart’s findings that Western societies moved from materialist towards postmaterialist values, as more generations have “spent [their] formative years in conditions of economic and physical security” (Inglehart and Flanagan 1987: 1296; cf. Inglehart 1977; Inglehart 1981; Abramson and Inglehart 1992; Inglehart and Abramson, 1999). Changing values “are reshaping religious beliefs, job motivations, fertility rates, gender roles, and sexual norms and are bringing growing mass demands for democratic institutions and more responsive elite behavior” (Inglehart and Welzel 2005: 15). With the shift to postindustrialism, the values that gain salience are those connected to “self-expression (…), through which people place increasing emphasis on human choice, autonomy and creativity”, and self-expression (Inglehart and Welzel 2005: 20–21). Are they also affecting the structure of our visual cultural artifacts towards a certain direction? And since the analysis of such a huge amount of images renders it impossible to analyze them at the figurative level, is it possible to trace such changes beyond the figurative level to the plastic (abstract) level?

4. Discussion

One could visualize entropy by comparing one of the most entropic with the least entropic album cover artworks in my sample. A reference to the cultural context of their publication can induce the meaning of the two covers:

Image 1. D. Savvopoulos, “To Perivoli tou Trellou” [A Fool’s Garden] (1969). This album cover’s entropy is 7.59279.

The first cover (image 1) comes from the late sixties (1969). One could suggest that entropy was the cultural mood of the era: hippie culture, weed, Rock, Vietnam, peace movements, May 1968; a world in constant motion, turbulence and unrest. What is more: this unrest was in a strict contradiction with domestic rule – the military dictatorship imposed in April 1967. Thus, beyond the visual signs (and maybe, even, as a clue to their “deciphering”), entropy could be a second order sign, signifying sympathy with youth movements throughout the West that could be overlooked by the censorship mechanism.

Image 2. En Plo, “En Plo” [On Board] (1989). This album cover’s entropy is 0.218448.

The second cover (image 2) comes from the late eighties (1989). It is the cover of the only album by an alternative, underground group. I think that the intertextual reference to The Beatles so-called ‘white album’ is quite strong, not only because of their perceived similarity (actually, the latter has even less entropy than the former), but also because of their ironic connotations. Produced at a period when the expectations of a whole decade seemed to vapor among political scandals, together with a complete change of the prevailing socio-cultural and economic values, the purity of the cover seems at once impossible, romantic and utopic.

One should mention, though, that this example shows that even if we expect visual cultural representations to become more entropic, the correlation between entropy and time is not linear.

The difference in entropy between the two covers is evident without need to use any instrument but the eye. What happens when the researcher is confronted with a huge number of images, with slight differences between them – something like ‘the 24,066 shades of grey’? In that case, the quantitative approach seems unavoidable. From a sociological viewpoint, one could manipulate numerical data, proceeding towards a sort of quantitative visual semiotics, which I will now try to showcase. But will it still be ‘semiotics’?

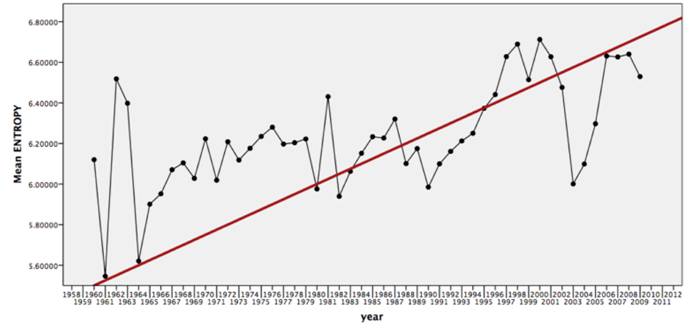

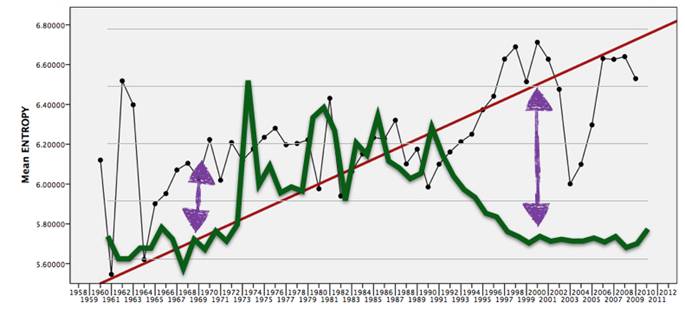

First of all, new types of visualizing a kind of sign available for quantitative manipulation are possible. For example, we can follow the fluctuations of entropy on the album covers from 1960 to 2010 as an expression of cultural dynamics (fig. 1).[2]

Fig. 1. Mean entropy on the album covers’ artwork per year (1960–2010).

In figure 1 one may observe that there is a trend towards an increase in entropy, which might have been expected if we mechanically transfer the second law of thermodynamics into cultural systems. But, as Arnheim has noted (1971), we should not take the law as a universal constant and use it in cultural artifacts. What is evident in this diagram is that the mean entropy of all albums’ artwork shows an interesting pattern, with micro-trends in periods of stability, fluctuations in periods of crisis, sudden turns to a different direction, and so on.

There is fluctuation in the period of military dictatorship (1967–1974); a sudden but short term fluctuation with no direction at the beginning of the 1980s, when Greece turned from a long period of rule of the political Right to a socialist government with strong leftist overtones; a decrease in entropy during the second half of the 1980s, when the cultural values begun to change due to the incorporation into European Union, but also to an economic crisis and austerity measures, followed by political scandals and unstable short-lived governments; a steady increase during the 1990s, when a new modernizing effort was undertaken; a sunk during a legitimacy crisis in the early 2000s, followed by an increase after the 2004 Athens Olympics; and a stabilization the years before the current economic, political and cultural crisis, which is not represented in my sample.

What may be inferred from such a reading is that “entropy”, as well as other similar measures seem to be related to the cultural, political and social environment within which they are encoded and decoded. There may be no single referent (or signified) for such kind of signs, but they still deliver a message.

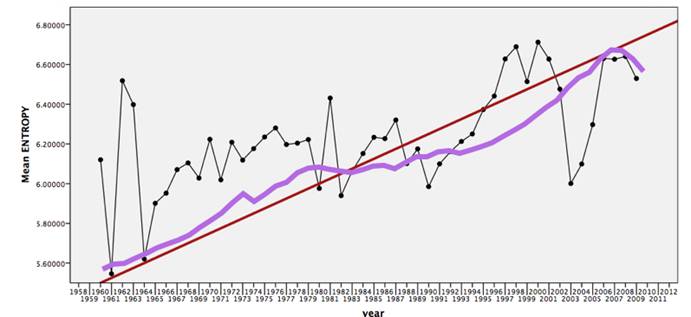

Though entropy in visual messages may relate to socio-cultural reality, it is hard to find data for long periods spanning half a century. I experimented co-relating entropy dynamics to changes in socio-cultural indicators. For instance, I compare entropy with Gross Domestic Product.[3] As is clear in this figure 2, the GDP rise follows the entropy trend, though no evident relationship with short-term fluctuations is found.

Fig. 2. Mean entropy of album covers’ artwork compared to GDP in constant 2000 USD (1960–2010)

In fig. 3 I compare entropy with inflation rate.[4] There appears to be a tendency for a rise in entropy in periods of low inflation rates, which is compatible with our hypothesis: low inflation rates mean economic security, hence the opportunity to pursue personal goals, and promote individualism vis-à-vis society. In any case, the lack of longitudinal data for the whole period don’t allow for a definite thesis on the connection between visual entropy in cultural artifacts and post-materialist or mixed values.[5]

Fig. 3. Mean entropy of album covers’ artwork compared to inflation rate (1960-2010)

5. Conclusion

Music albums’ cover artwork is an intriguing cultural and communicational artifact, similar to advertisements as well as all other forms of mass images, appropriate for semiotic research. Album covers are available in digital form, since they are collectible by themselves, as well as since they form part of the metadata used for the digital promotion and sale of music. The digitized covers available to visual researchers are, therefore, much more than any semiotician could hope to see – and hence to analyze. It is exactly this amount of available data that calls upon us to face new challenges in socio-semiotics, cultural semiotics, as well as the semiotics of cultural change.

Our semiotic traditions, used to the analysis of exemplar items rather than huge collections, are not helpful enough to answer such challenges. In this paper I have proposed the search for signs that may be discerned through computer software and be abstractly presented in quantitative terms. These signs have certain communalities with the ones suggested by Groupe μ for the analysis of plastic (non figurative) signs: entropy; mean values for red, green and blue; hue vs. saturation. Actually, taking the first steps in the realm of big visual data, the distinction between iconic and plastic signs is loosing importance, while the available toolset allows for the transition from the concrete forms to the abstract quantitative signs.

With the example used in this paper, I have shown that such an approach is possible; that it may be further visualized; and that it allows – inter alia – the understanding of the temporal dynamics of visual signs, as well as its co-relation with cultural and social variables.

To be sure, this attempt is still highly experimental, and there is a need for further experimentation with other measures beyond entropy, in order to fully grasp the possibilities of a quantitative visual semiotics.

References

Abramson, Paul R. & Ronald Inglehart. 1992. Generational replacement and value change in eight West European societies. British Journal of Political Science 22 (2). 183–228.

Acock, Anthony. 2014. The misrepresentation of Punk identity in design, advertising and media. Paper presented at the Punk Culture Conference of Popular Culture Association / American Culture Association, Chicago, 16–19 April.

Alleyne, Mike. 2014. After the Storm: Hipgnosis, Storm Thorgerson, and the rock album cover. Rock Music Studies 1(3). 251–267.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis & Arno Scholz. 2003. Spaghetti Funk: Appropriations of hip-hop culture and rap music in Europe. Popular Music and Society 26(4). 463–479.

Arnheim, Rudolf. 1971. Entropy and Art: An Essay on Disorder and Order. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Barthes, Roland. 1977. Rhetoric of the Image. In Roland Barthes, Image Music Text, 32–51. London: Fontana Press.

Bartmanski, Dominik, & Ian Woodward. 2013. The vinyl: The analogue medium in the age of digital reproduction. Journal of Consumer Culture online first publication (2013): 1–25.http://joc.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/05/30/1469540513488403.full.pdf (accessed 4 January 2015).

Bestley, Russell. 2014. Art attacks and killing jokes: The graphic language of punk humour. Punk & Post Punk, 2(3). 231–267.

Blue, Al W. II. 2011. African Americans on Album Covers: A Pictoral Essay Volume 1. Bloomington: AuthorHouse.

Brett, Thomas. 2015. Autechre and Electronic Music Fandom: Performing Knowledge Online through Techno-Geek Discourses. Popular Music and Society 38(1). 7–24.

Chapman, Ian Charles. 2012. “I looked and frowned and the monster was me”: David Bowie’s progression from mod to freak as traced through his album covers, 1967-1974, Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago doctoral thesis.http://otago.ourarchive.ac.nz/handle/10523/2509 (accessed 4 January 2015).

Dragoumanos, Petros. 2007. Κατάλογος ελληνικής δισκογραφίας 1950–2007 [Greek discography catalog 1950–2007]. 6th edition. Athens.

Fiore, Adriano Alves & Miguel Luiz Contani. 2014. Argumentative elements of bakhtinian carnivalization in the Iconography of Heavy Metal. Bakhtiniana 9(1). 36–53.

Fullerton, Lindsay & Matthew Rarey. 2012. Virtual materiality: Collectors and collection in the Brazilian music blogosphere. Communication, Culture & Critique 5. 1–19.

Grant, Angelynn. 2001. Album covers design: Past influences, present struggles and future predictions. Communication Arts 42. 83–94.http://angelynngrant.com/pdfs/AlbumCoverDesignFinal.pdf (accessed 4 January 2015).

Groupe μ. 1992. Traité du signe visuel: Pour une rhétorique de l’image. Paris: Seuil.

Hickam, Brian & Jeremy Wallach. 2011. Female Authority and Dominion: Discourse and Distinctions of Heavy Metal Scholarship. Journal for Cultural Research 15(3). 255–277.

Huss, Hasse. 2000. The “Zinc-Fence Thing”: When will reggae album covers be allowed out of the ghetto?” Black Music Research Journal 20(2). 181–94.

Inglehart, Ronald. 1977. The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles among western publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald. 1981. Post-Materialism in an Environment of Insecurity. The American Political Science Review 75(4). 880–900.

Inglehart, Ronald & Paul R. Abramson. 1999. Measuring Postmaterialism. The American Political Science Review 93(3). 665–667.

Inglehart, Ronald & Scott C. Flanagan. Value Change in Industrial Societies. The American Political Science Review 81(4). 1289–1319.

Inglehart, Ronald & Christian Welzel. 2005. Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inglis, Ian. 2001. “Nothing You Can See That Isn’t Shown”: The Album Covers of the Beatles. Popular Music 20(1). 83–97.

Jones, Steve & Martin Sorger. 1999. Covering Music: A Brief History and Analysis of Album Cover Design. Journal of Popular Music Studies 11–12(1). 68–102.

Karjalainen, Toni-Matti & Antti Ainamo. 2011. Escapism signified: Visual identity of Finnish heavy metal bands. In Proceedings of the IASPM Benelux Conference, 31–48. Haarlem, the Netherlands.

Karjalainen, Toni-Matti, Laura Laaksonen & Antti Ainamo. 2009. Occult, a Tooth, and the Canopy of the Sky: Conceptualizing Visual Meaning Creation of Heavy Metal Bands. Paper presented at DeSForM 2009, Taipei, 26–27 October.

Lowey, Ian & Suzy Prince. 2014. The Graphic Art of the Underground: A Countercultural History. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Manovich, Lev. 2013. Software Takes Command. New York & London: Bloomsbury.

Marques, Oge. 2011. Practical Image and Video Processing Using MATLAB. New Jersey: Wiley.

Pardue, Derek. 2005. CD cover art as cultural literacy and hip‐hop design in Brazil. Education, Communication & Information 5(1). 61–81.

Pardue, Derek. 2010. Making territorial claims: Brazilian hip hop and the socio-geographical dynamics of periferia. City & Society 22(1). 48–71.

Robertson, Matthew. 2007. Factory Records: The complete graphic album. London: Thames and Hudson.

Schmitt, H., E. Scholz, I. Leim, and M. Moschner. 2008. The Mannheim Eurobarometer Trend File 1970-2002 (ed. 2.00). ZA3521 Data file Version 2.0.1. Cologne: GESIS Data Archive.

Schwarz, Hunter. 2012. How many photos have been taken ever? BuzzFeed, September 24. http://www.buzzfeed.com/hunterschwarz/how-many-photos-have-been-taken-ever-6zgv#.ndwx0WmRw (accessed 4 January 2015).

Serazio, Michael. 2008. The Apolitical Irony of Generation Mash‐Up: A Cultural Case Study in Popular Music. Popular Music and Society 31(1). 79–94.

Shaw, Andrea Elizabeth. 2014. “The gaze of the natives”: Visualizing reggae music as CD artwork. Palimpsest: A Journal on Women, Bender and the Black International 3(1). 33–49.

Sonka, Milan, Vaclav Hlavac & Roger Boyle. 2008. Image processing, analysis, and machine vision. 3rd Edition. Toronto: Thomson Learning.

Thum, Ch. 1984. Measurement of the entropy of an image with application to image focusing. Optica Acta: International Journal of Optics 31(2). 203–211.

Toivanen, Arja. 2014. Fan’s affect for music record formats - From vinyl LP to MP3. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä Master’s Thesis.

Weston, Donna. 2011. Basque pagan metal: View to a primordial past. European Journal of Cultural Studies 14(1). 103–122.

[2] The first four years of the period examined here are represented with only 12 covers, which makes impossible to make any valid observation for them.

[3] The GDP data were obtained from the Index Mundi website (http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/greece/gdp)

[4] Inflation rate data were obtained from the Trading Economics website (http://www.tradingeconomics.com/greece/inflation-cpi)

[5] Eurobarometer studies offer a time-series from 1980 (when Greece was accepted in European Union) until 1995 (Schmitt et al. 2008). After 1995 the materialism/postmaterialism questions were asked only sporadically.