ALBUM COVERS: DISCOVERING BRAZILIAN LIFE UNDER MILITARY DICTATORSHIP

Faculdade Cásper Líbero, São Paulo, Brazil

Abstract

Brazil lived under military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985. The censorship was fierce and the freedom of speech too limited. At the dictatorship’s final period, in Sao Paulo city, Brazilian biggest city and cultural pole, some musical groups and artists of many areas began to trace open critics to the government and to the situation they were living. This movement was called as “Vanguarda Paulista” (Paulista Vanguard), and those who were part of it had a strong political and social sense, besides the esthetic preoccupations. “Língua de Trapo” was a group of this movement, and they became quickly known not only due to their acid lyrics, but also due to their humanistic and liberal look, perceptible in the critics to the social behavior. Humor had always been present in the compositions and performances of the group that tried to talk about themes such as political freedom, sexual orientations, urban violence and censorship in a different way of those who were known as “singers of protest”. The humorous and critic spirit of the group appeared in the cover of the albuns and, if it was read as a text, it could show a Brazilian portrait in a particularly important moment of the country’s contemporaneous history. This paper presents a brief frame of Brazilian political situation in the mentioned period, the artistic production of “Língua de Trapo” and how their album covers were already showing a political, ideological and artistic positioning. Reading the image as a complex text in order to analyze and to interpret Brazilian’s socio-historical context will enable to understand the language and the messages in the album covers of “Língua de Trapo” and show a group worried to mark not only a contemporaneous esthetic but also their own political positioning in a very troubled time for Brazilian life. This study is based on theoretical concepts and texts from authors such as Guy Debord (Society of the Spectacle), Adorno and Horckheimer (Cultural Industries) and Michel Foucault.

The musical group Língua de Trapo was one of the exponents of the self-called Vanguarda Paulista, artistic movement in São Paulo city in the late 1970s and during the 1980s. The group's music and his performance on stage were mocking political and social criticism in the final period of the Brazilian dictatorship.At a time when censorship still had strength, dealing with sensitive issues such as education, marginalized child or sexuality could lead to problems for artists.

The social criticism, political positioning and the way of the band look to the facts of life came from the critical view of its components. Using not only the songs, but the covers of albums, the group could pass political messages and depicting the moment that was lived in Brazil.

Knowing the social and political profile of a society at a given time is the basis for understanding the cultural production of this society. For his unique style of blending humor, and political and social criticism, and have originated from a vanguard movement, the Língua de Trapo has never been a successful name in the mainstream, remaining outside the music business.

Guy Debord’s Society of The Spectacle (1997), helps to understand the media coverage and the everyday life. The group used parody in his music production, a style widely discussed by Fredric Jameson (1996). The discussion about the Culture Industry is based on works by key authors such as Adorno and Horkheimer, which helps us to contextualize the subject studied here.

From dictatorship to opening: the stage for the show starts to be mounted

On March 31, 1964, Brazil went to sleep as a democratic state under the rule of civilian President João Goulart and waked up on April 1 under a military dictatorship.The long period of exception lasted until the indirect election of Tancredo Neves in 1985. Brazilians were prohibited from voting directly for governor until 1982 and for President until 1989. The return to democracy began in the government of General João Baptista Figueiredo (1979-1985), with the amnesty and the restoration of multiparty system. Communist parties remained prohibited.

Military dictators have used every trick to maintaining power, including the censorship of news and political and cultural manifestations. The gates of hell were opened by the Institutional Act number 5, which overlapped the national and state constitutions, strengthened the hardliners and gave absolute power to the military regime. Brazilians were gagged and cannot speak, dull because they could not hear and blind, unable to see anything beyond what pleased the military dictators.

Cultural life also suffered direct persecution, both by censorship (milder between 1964 and 1968, absolute thereafter), which prevented the free expression of ideas and the arts, as the physical repression set in prisons and torture. After 1968, any criticism of the dictatorship was taken as a subversive and communist attitude, and therefore, liable to punishment (Ridenti, 2005, p.72). At the end of his performance, coinciding with the end of dictatorship, censorship was tested, and sometimes ignored by artists who appeared at the same time that Brazil began to return to democracy. In 1985, the conditions for the flourishing of new political and cultural settings were launched, and some already arose in the Brazilian horizon.

At the time, Brazilian Popular Music (MPB) lived in a comfortable complacency setting with big names turning into sacred cows, consecrated already becoming gods and an occasional composer / singer doing almost sealed letters of protest, because of censorship."The ways of Brazilian music were very grim: the labels were absolutely closed to anything that would indicate renewal or, at least, were extremely remote from Sao Paulo scene" says Wilson Souto Jr., owner of the space that would be known as the cradle of Vanguarda Paulista, the Lira Paulistana (Alexandre, 2002, p.42).

Certain musical groups from this scene started getting gigs more often and drew public attention, from critics and also the "pachydermic music industry that came out of hibernation and began to suspect that something happened in the cultural underworld of Sao Paulo" according Nasi, lead singer of IRA!, contemporary band from Vanguarda Paulista. (Beting, 2012, p.78).

It is part of the culture industry logic holds the absolute control of the production of the music industry, with an eye on profit, capturing popular cultural events and turning them into salable products. "Do- it-yourself” was one of the slogans of the punk movement, that is, do not wait others to do for you. This meant seeking new ways to record and disseminates the songs themselves, without depending on major labels and their standardized systems.

In Brazil the years 1980, MPB was self-indulgent and autophagy, sterile (Dapieve, 1995), in fault of the military regime and elites holding political and economic power and the consequent imposition of the dominant culture (Tinhorão, 1990). To be different had to get away from the standard. To record an LP, it was necessary to devise alternatives. You had to get away from the mainstream, turn your back to the record companies, commercial radio, the powerful Globo TV network and its plastic novelties. The little room for independent bands was possible thanks to the college radio, separated from the major labels and without the worry of producing a profit for their owners.

The new counterculture should be against the military regime, show new values , breaking with the MPB. The speech was the non-speech, lift something new from the collapse than existed before (Alexandre, 2002). Unlike the musical movements until then, the artists of Vanguarda Paulista approached the divergence in dislike of the reigning sameness. The similarity between them was an aesthetic concern and an absence of formal ways. There was only one consciousness to do something different from what was already absorbed by the industry.

There is a direct relationship between cultural production and the capitalist economic output, as this allows the projection of the laws of the market to the field of production and dissemination of popular music (Tinhorão, 1990).

But there is a filter in the cultural industry that allows only the groups or artists linked to large companies, or sponsored by them artistically, access to mass media such as radio and television, making it virtually impossible for independent artists and groups to stick this block. What is heard in the mass media is not the authentic taste popular, but false, artificial-produced by the holders of the economic and media power.

The culture of defense is not based solely on artists of a certain counterculture movement (Dunn, 2008). Other elements are needed for the rallying cry is heard and perceived socially. The symbolic production (Bourdieu) followed the procedures ever; after all, was guided by a conservative market, averse to independent news. And when something came up independent, was soon co-opted by the same industry.

All production value and meaning of an artistic movement depends on a variety of political actors (end of dictatorship and democracy), social (relationship of the members of Vanguard Paulista), artistic (no new or strong movement in music), producers (had to get away from the major record labels to show something different), critical (almost always aware of what happens around you) and consumers (the public was unhappy with the MPB).

In a scenario full of domination in the production and dissemination, and by extension, cultural and social control, the Rag language sought to show that it was possible a new form of musical expression. The Brazil in the late 1970s and early 1980s lived the agony of a dictatorial period. Musical movements of importance no longer prevailed. The company wanted political, economic and social changes. The stage was set for the show.

The Vanguarda Paulista and Língua de Trapo: São Paulo´s songs

The Vanguard Paulista had an innovative and challenging attitude to popular music. It was an interconnected group, but independent, artists, writers and musicians who lived in São Paulo. Categories such as avant-garde, alternative, independent and marginal are used to refer to a generation that has established in São Paulo and produced from the town (Oliveira, 2002, p.61).

São Paulo universities were barns talent and always appeared groups that were soon performing in São Paulo night. From Journalism course at the Faculty Casper Libero came, in 1979, the Laert Sarrumor & os Cumplices. With the entry of other students, as Guca Domenico, Antonio and Carlos Mello, the group was soon renamed Língua de Trapo (as whisperous, a popular expression in Brazil). The choice fell on the name Ari Barroso's song "Dá Nela" (beat her) because the so rag language spoke ill of everything and everyone around you.

The songs were pretentiously serious, but the group itself did not take him seriously. At shows the use of political humor in the lyrics generated identification with the public, because the historical moment of Brazil was conducive to this kind of music. The source of inspiration were the things of everyday life, society itself with its habits and bad habits, politicians and their actions, often suspected. The band tried to pick on everyone, using humor as a weapon to complaints that can laugh generate transformations in society at the time. The musical production of the group is composed of the following discography:

· Língua de trapo (1982);

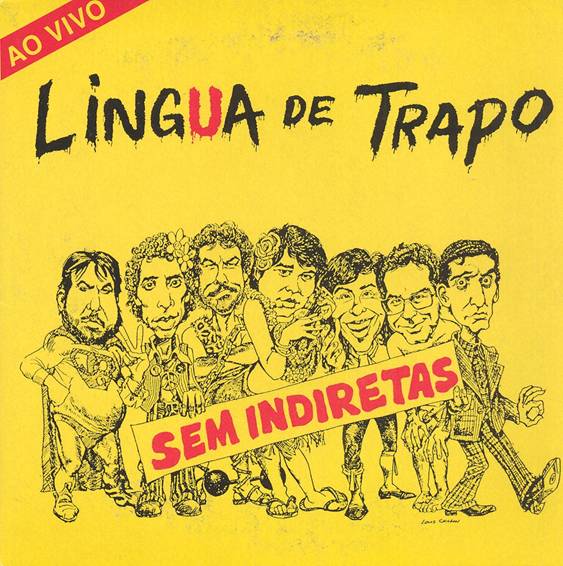

· Sem indiretas (1984);

· Como é bom ser punk (1985);

· Dezessete big golden hits super quentes mais vendidos do momento (1986);

· Brincando com fogo (1991);

· Língua ao vivo (1995);

· Vinte e um anos na estrada (2000);

· Vinte e um anos na estrada – DVD (2000)

Língua de Trapo and the cultural industry

The cultural industry, with the domain and the exploitation of mass media by financial, common groups in capitalist countries, democratic or even exclusively by the government in countries with closed political system, it generates a uniform cultural events. What is displayed can only be so if it is within the standard of those in power. "The whole world is forced to pass through the filter of the cultural industry" (Adorno, Horkheimer, 1985, p.118).

Thus, artistic productions such as movies, novels, texts and music go through an ideological sieve. The State and individuals controlling the mass media impose their ideology. And time also for marketing sieve, specifically in cases where the control of disclosure belongs to the private sector. In both cases, "even the aesthetic manifestations of opposite voltage dence policies sing the same praise of the steel rate” (Adorno, Horkheimer, 1985, p.113).

To break this pattern we must dare, build alternatives and try to conquer space to display their own artistic and cultural production, often an uphill battle and condemned from birth to defeat. For those who are not part of the mainstream, any artistic production outside the ghetto itself and conveyed, spread through the culture industry apparatus, whether on the radio, on television or in newspapers and magazines of high circulation, is only part of "an ideology intended to legitimize the trash that intentionally produce" (Adorno, Horkheimer, 1985, p.114).

In this view, all that is produced or aired by the culture industry lacks proper artistic value, it is not cultural event. To be served, automatically becomes part of the system. What displays and reports are then pasteurized products because they are harmless, and equal, not bring anything new. "The relentless drive attest cultural industry unit training policy" (Adorno, Horkheimer, 1985, p.116).

There was, as today is noticeable, a movement or a proto-movement to promote aesthetic and political changes in Brazil, which at that time spent by the military dictatorship of transition to democracy. And there was, above all, an attempt to escape the artistic and aesthetic uniformity that is striking feature of the cultural industry, where songs, artists and shows are repeated infinitely, varying only the form, not the content (Adorno; Horkheimer, 1985).

The search for new styles and forms of artistic expression outside the mainstream just offering the very culture industry a source of new material, and, through a process of assimilation and control, allows the continuous exercise of domination and perpetuate this domination. The aesthetic and artistic breaking claim of the vanguards ends just feeding what you wanted to destroy. As much as the ideological pretensions of artists are evident, that his works are imbued with aesthetic concepts, artistic or political opposite to the dominant pattern, "as recorded in its difference by the culture industry, he (the artist) now belongs to it as well as the participant of agrarian reform to capitalism" (Adorno; Horkheimer, 1985. p.123).

The artist also passes through the filter of cultural industry (Adorno; Horkheimer, 1985, p.123), otherwise it will be virtually impossible to survive the production of his work without some kind of marketing, without consideration for the assignment of an artistic production or it is shelter, patronage or money. To not give up their artistic concepts or parts of them, to be inflexible, the artist is condemned to ostracism media and eternal stay in the shade and the lack of recognition by the mass. Offers an oblation to the marginal gods, but never surrender to industrial god.

If slightly flexible to appear and be accepted by the culture industry, the artist is branded as sold by their peers. However, if it does not, get the marginal image of the system. If this insertion in the cultural industry is made independently of his will to participate in disclosure, or to see their proper work by others, the artist himself becomes part of what before criticizing, which used to be excluded (Adorno; Horkheimer, 1985).

Albuns covers

In some of his songs, using unusual image constructions, absurd or funny situations, the Língua de Trapo makes use of something "legitimate in folk art, farce and buffoonery" as Adorno and Horkheimer (1985, p.129) in an attempt to, through laughter, cause a political debate, denouncing through the farcical something that is explicit, but is not seen in society.

"We laughed about the fact that there is nothing to laugh about" (Adorno, Horkheimer, 1985, p.131). We laughed because we are placed in the position of observers something that showed and did not see. Laughed the equivalence of historical characters, the courage to use a historical fact and pain that occurred there, as we laugh, mainly by discovering ignorant of our present. We laughed our own ridiculous. True joy is a serious thing (res severe gaudium verum). Laughter helps to break the reality, changing customs, thoughts change, to become more critical to perceive situations from another angle (Adorno, Horkheimer, 1985).

Every album cover image is taken as a social text and can be read as such, with the name of the band, and the disc of the images used. The image (and, by analogy, the album cover) is a social practice of producing texts that arise within social practices in which we engage, within the social institutions in which we live (Foucault, 1969).

The use of images in music production – in this case, the albums covers – has a force that should not be neglected as it is the first consumer identification with the product (vinyl, CD or DVD) released by the artist. A needy time information often mutilated by censorship, image album cover offered (and still offers) a quick way to understand the spirit of a musical work or the message that the band wants to show.

The compact “Sem Indiretas" (Figure 1), with two songs live from the eponymous show, use the yellow, the official color of the Direct Elections Now movement. The red stripe on the top left of the cover art highlights that it is a live disc recorded. The band's name appears written as if it had been spray-painted on a wall with dripping paint each letter. The letter U symbolizes a language and was spelled in red. This image refers to political graffiti that at that time abounded in walls throughout São Paulo, in phrases like "Down with the Dictatorship", "We want democracy" and the most famous of all, "Direct Elections Now".

The components of the band appear in caricatures designed, with each taking one character. These cartoons, far from childish the band, show the sense of humor that was already trademarked the group and how they took the characters that appeared in their songs live. In front of everyone, like a stripe of censorship, the band with the name of the show and the album "Sem indiretas" reference to the political moment that the country was with the group giving their support to the movement for elections direct to the President and the end of the Electoral College.

Figure 2. “Como é bom ser punk” (It´s good to be punk)

The group used on the cover Ladies Concert at the Philharmonic Hall framework, by the Venetian painter Francesco Guardi, painted in 1782 and currently exposed in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. This represents a party hosted by the Austrian court to the Russian nobles visiting Vienna.

The album cover is composed of a thick red band and a thinner yellow that frame the painting. The band's name appears above all the elements. And between the name and the ballroom chandelier (focal point frame) appears the disk name: It´s good to be punk. The word punk is written in red and seems to have been graphitized because around for ink splatters and his spelling was made irregularly. Shows some strength and aggressiveness, in contrast to the mild and calm environment of the frame.

The punk movement shocked traditionalists by the speed of the music, the themes and the visual aspect of his followers. Nothing more traditional and conservative than life in a court. The cover shows how would a visual contrast between the rigid court life with a punk presence, through word of graffiti on the board. The punk movement in Brazil was at its peak in 1985, while in Europe begins to take the first signs of exhaustion.

The visual joke album cover end up gaining more strength by hearing the homonymous song, in which a punk who works as an office boy sings his difficulties through a parody of opera singing.

Pastiche and parody or sameness and creativity?

Postmodernism: the cultural logic of late capitalism (1996), by Fredric Jameson, allows us to discuss of parody and pastiche of concepts in contemporary society, illustrating the various ways you can understand artistic events that occurred in the late 1970s and for much part of the 1980s in São Paulo. The period in which the dictatorship and censorship were in full force can be known today as the time of pastiche and the simulacrum to the musical art world, although this pastiche scenario can also be recognized today. The strong presence of the heavy hand of censorship was something that all artists should count, therefore, for a work to be shown on television, theater or cinema, for a song to be recorded to disc, played on the radio and concerts , approval was required Department of Censorship of the Federal Police. And what was contrary to mainstream thinking, produced by critics of the dictatorship, or fleeing the standards imposed by the censorship was summarily banned.

There was thus the artistic standardization, with the annulment of the individual subject and its creative manifestations, predominantly repeat artistic and musical styles. In addition to censorship, the desire to succeed was an important factor (and still is) the emergence of "new" singers and groups that simply repeated in style and content, without really anything new to offer. It is a sad combination of artistic censorship with political and moral motivations with the strength of the cultural industry.

Pasteurization of art caused by the artistic production within the logic of the culture industry, quickly becomes the main artistic events in a gray and indistinct panel, where what prevails is not the creativity and, yes, the accommodation of the artists chewed formulas and repeated that can ensure more profitability for the least cost to the holders of the means of production. "The autonomy of works of art, which, it is true, almost never existed in pure form and that has been marked by causal connections, you see, ultimately, abolished by the culture industry" (Adorno, 1994, p.93).

This relentless pursuit of standardization of artistic works results in a high degree of dissatisfaction in those who are excluded from disclosing media artwork and own mass art production chain. One of the ways to earn a place in the sun and show their work is to opt for independent production and dissemination, knowing beforehand be impossible to compete on the same level with artists, musicians, singers and groups sponsored by the cultural industry, with radio stations, television and large record labels. It is the most extensive and complete dependence and servitude. "The compensatory satisfaction that the cultural industry offers to people, to awaken in them the comfortable feeling that the world is in order, frustrates them in their own happiness she deceptively gives them" (Adorno, 1994, p.9).

The ubiquity of the cultural industry almost impossible the formation of autonomous individuals, independent and, therefore, critical. These guys are the precondition of democracy, which never existed or would have survival guarantees the absence of independent thinkers and critics of cultural industry (Adorno, 1994, p.99).

Promoters of marketed fun wash their hands when they state that they are giving the masses what they want. This is an appropriate ideology for commercial purposes: the less the mass can discriminate, the greater the possibility of selling indiscriminately cultural items (Adorno, 1994, p.136).

The text section "About popular music," by Adorno, helps you understand how strong and damaging the conjunction of cultural industry with a totalitarian regime in capitalist societies. This switches to cultural industry not only in favor of capital development, but also as disclosing the dominant political thought.

By focusing on lack of reasoning of a population that accepts without blinking, for convenience or fear of retaliation, any artistic or cultural events that are imposed, the government of a dictatorial regime seeks ways to impose their "taste" and the musical aesthetic population. It does this through the commercial interests of the cultural industry. Those who do not pray for official booklet, or, in this case, do not sing the official sheet music, automatically staying to the disclosure system edge through radio and commercial television stations, surviving only through local shows with reduced public and sale tiny runs of LPs or cassette tapes produced alternatively.

What is the path used by Rag language with their album covers, music and lyrics to face the military dictatorship and the cultural industry? Parody against pastiche, the mood against violence, free thought against dogma. The intolerance towards the standard. Against dependence and servitude, freedom and liberty.

Pastiche, such as parody, is imitate a style, a mimic coarse, repetitive and not creative because creativity requires freedom to be able to create, not plastered and standards. It is a dead expression, like a statue without eyes. Have parody serves to provoke laughter, to embarrass or honor. "Pastiche does not have life or the mood of a parody, because it lends itself to provide information required for a more critical pension cessing from the observation of what has been parodied" (Jameson, 2000, p.44).

What capitalist society produces is pastiche, a mere imitation of artistic styles in several industrialized artistic events. It is an almost eternal repetition, dull and creativity, artistic events that at some point had a glimpse of innovation, but were absorbed by capitalist society (Jameson, 2000). The way to denounce the artistic sameness, pastiche that reigned in MPB and the social and political problems experienced in Brazil during the study period was the parody lyrics and musical styles, and the images used on the albums covers.

Freedom of choice of musical rhythms shows how much the group valued artistic freedom and political independence. In a disc of the band can be heard moda de viola, hard rock, bolero, reggae, xote and parody of Italian music. And the lyrics do not spare political parties, business, government and religions. Commented acidly about everything and everyone.

This imitation, pastiche, again, is not as parody. Are different in essence and in its acts. They differ in purpose and function. While the parody is used to laugh, exaggerating features of particular work, manifestation or artistic style and thus enabling a discussion of the provocation made , pastiche lacks critical sense.

Just try to play through mimesis, qualities or characteristics of certain artistic works, making the play by play, headless and uncritical, with the intention of no longer a just and yes, also earn some money and another that is the same as the market. "The pastiche is the simulacrum of an artistic work, it lacks originality and aura, being identical copy of something whose original never existed” (Jameson, 2000, p.45).

Reinforcing the hypothesis of creative empty pastiche of artistic expressions coming from a consumer society, Guy Debord states that "the image will be the final form of reification," since the most important thing seems to be rather than being. This seems to be, no matter individual artistic value, but the value that particular artistic expression is replaced by look, to resemble other artistic expression. This manifestation, in turn, came from a simulation of another manifestation, perpetuating the pastiche as is the work of Sisyphus, never ending and always produces the same result, condemned to eternal repetition.

By this time being dominated by pastiches and simulations, the last time tends to disappear from the historical memory of a society, as the pastiche reproduces itself, not allowing innovations.

Língua de Trapo was critical in its time, which confirms that "there is more engaging historical relic than the music of certain periods” (Wisnik, 1982, p.15). Songs with critical content, most often using humor and parody to show what the group saw as wrong. Errors that persist in haunt our daily lives, even after so many years, after the dictatorship and six presidents of the Republic elected by direct vote of the Brazilians.

References

ADORNO, T. A Indústria cultural. In: COHN, G. (Org.) Comunicação e indústria cultural. São Paulo: Ática, 1994. ADORNO, W.T; SIMPSON, G. Sobre música popular. In: COHN, G. (org.). Theodor Adorno: sociologia. São Paulo: Ática, 1986.

ADORNO, T. e HORKHEIMER, M. Dialética do esclarecimento Zahar Editor: 1985.

ALEXANDRE, Ricardo. Dias de luta: o Rock e o Brasil dos Anos 80. São Paulo: DBA: 2002.

BARTHES, Roland. O óbvio e o obtuso. São Paulo, Nova Fronteira, 2009.

BAUDRILLARD, J. Simulacros e simulação. Lisboa: Relógio D’Água Editores, 1991.

BAUDRILLARD, J. O sistema dos objetos. São Paulo: Ed. Perspectiva, 2a Edição 1989.

BENJAMIN, W. A obra de arte na época das suas técnicas de reprodução In: Textos escolhidos. São Paulo: Abril Cultural, Col. Os pensadores vol. XLVIII, 1975, p.9-34.

BERGSON, Henri. O riso: ensaio sobre a significação da comicidade. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2004.

BETING, Mauro. A ira de Nasi. Caxias do Sul: Editora Belas-Letras, 2012.

BOURDIEU, Pierre. A economia das trocas simbólicas. Perspectiva, 2009.

DAPIEVE, Arthur. Brock: o rock brasileiro dos anos 80. São Pau- lo: Editora 34, 1995

DEBORD, Guy. A sociedade do espetáculo. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 1997.

DIAS, Márcia. Os donos da voz: indústria fonográfica brasileira e mundialização da cultura. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2000.

FAGUNDES, Coriolano de Loyola Cabral. Censura e liberdade de expressão. São Paulo: Edital, [s/d].

FOUCAULT, Michel. Arqueologia do saber. 7. ed. Rio de Ja- neiro: Forense Universitária, 2008.

HAUG, Wolfgang F. Crítica da estética da mercadoria. São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 1996.

HORKHEIMER, Max & ADORNO, Theodor. A indústria cultural: o iluminismo como mistificação de massas. In: LIMA, Luiz Costa. Teoria da cultura de massa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2002, p.169-214.

JAMESON, F. Pós-modernismo: a lógica cultural do capitalismo tardio. São Paulo: Ática, 1996.

LIMA, Venício. Mídia, teoria e política. São Paulo: Perseu Abramo, 2001.

OLIVEIRA, Laerte Fernandes. Em um porão de São Paulo. São Paulo: Annablume, 2002.

RIDENTI, Marcelo. O fantasma da revolução brasileira. São Paulo: Editora da Unesp, 2005.

SKIDMORE, THOMAS E. Brasil: de Castelo a Tancredo. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2004.

TINHORÃO, José Ramos. História social da música popular brasileira. Lisboa: Caminho, 1990.

TRIVINHO, Eugênio. O mal-estar da teoria. A condição da crítica na sociedade tecnológica atual. Rio de Janeiro: Quartet, 2001.

WISNIK, José Miguel. Música. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1982.