NEW MUSICAL SEMIOTICS? INNOVATION THROUGH TRADITION

University of Turin, Italy

gaber.en@libero.it

Abstract

The essay addresses the problematic development of musical semiotics within general semiotics and in comparison with other applied semiotics. It is suggested that it is possible to recover key notions and analytical tools from the tradition of the discipline in order to develop Greimas’ project further; namely, that the seed of innovation may be grounded in routes that have already been explored by the discipline, not outside of its domain. In particular, by referring to the proposal by Jacoviello, it is suggested to recover the semiotics of plastic arts or plastic semiotics, as elaborated by the Paris School with regard to visual texts such as non-figurative or abstract paintings, in order to deal with such an “ineffable” matter as sound and music.

0. Intro

In the capacity of the co-chair of the Musical Semiotics session of the 12th World Congress of Semiotics, along with Prof. Eero Tarasti (the session was held on Sept. 16, 2014, at the New Bulgarian University, Sofia, Bulgaria), by the present paper I would like to propose just some brief notes upon the topic of the symposium itself; namely, the dialectics between tradition and innovation within semiotics and, in particular, musical semiotics.

1. Rehearsing in the garage: Music as a semiotic impasse

As you all know, music is a problem – A big one. A semiotic problem and, at the same time, a problem to semiotics, as a discipline. Philosophers, musicologists, linguists, and semioticians have struggled for decades trying to identify the semiotic status of music: is it a language or not and, in case, is it analyzable like natural language (structuralist “annexationism”); is it a sign and which type of sign (index, icon, symbol); does it carry meanings and are these meanings immanent (autonomy, endosemantic hypothesis, introversive analysis) or not (heteronomy, exosemantic hypothesis, extroversive analysis); are these meanings translatable into words (verbalizability) or are they ineffable (iconic, anti-reductionist hypothesis)?

In opposition to the infamous glottocentricism of the discipline (namely, its preference for the verbal language), some authors (Ponzio and Lomuto, Kramer, Tagg and Clarida) have suggested to consider music – not verbal language – as a model of how meaning works in general, precisely due to the blurry and problematic semiotic status of such matter – Why should meaning be such an easy business? Both Goitre and Lidov, independently got to ask themselves: “Is language a music?”.

The lexicon of semiotics, and its epistemological perspective, in the first place, were intimately contradictory, whereas not obscure at all, with regard to the musical domain. Benveniste claimed music was semantic, but non-semiotic. Lévi-Strauss was profoundly inspired by music, but still he claimed it had no actual meaning. Most of these issues, debates, and theoretical positions were actually pseudo-problems, but still they managed to slowing down the development of a dedicated branch of the discipline. Moreover, the peculiarity of the matter led to a semiotics which is very different from the other so-called applied semiotics.

2. Side one: The relationships with general and other applied semiotics

Musical semiotics grew by following a parallel course compared with so-called general semiotics, constituting, de facto, an independent, extremely specialized, and minority field, whose exchanges with the other so-called applied semiotics have always been scarce. As Tarasti maintains, “oddly enough, few of the great semioticians have said anything about music as sign” (2002: 4). Hjelmslev, Greimas, Lotman, and Eco, for instance, didn’t talk much about music. Barthes’ reflections on the topic were extremely fertile – think of the famous “grain of the voice” or to the notion of “somatheme” (the smallest somatic unit of meaning) – but still they were far from being systematic. Apparently, music was not worth a dedicated entry in the Dictionary edited by Greimas and Courtés; or, to be more precise, albeit a “Music” entry was originally featured in the 1986 volume (Castellana 1986), it was later expounded from the canonical version of the book.

As a matter of fact, as Monelle maintains, “the chief enterprise of music semiotics remains unfulfilled” (1992: 327), since there is no shared methodology among those who practice the discipline and their results are partial (they overlap with established musicological findings and they can be applied just to a small canon of works, critics maintain).

In fact, there is no such a thing as “musical semiotics”, but rather different musical semiotics projects (nearly as many as their proponents): there is the paradigmatic-stylistic analysis of the neuter level elaborated by Nattiez (in the footsteps of his masters Ruwet and Molino); there is a group of scholars and theories stressing the narrative component of music (Tarasti, Grabòcz, Samuels, Almèn); others focusing on music as gesture and embodied metaphor (Lidov, Hatten); others on the notion of “topic” (Monelle, Agawu); others developing a cognitive-interpretative perspective (Martinez, Cumming); there is the pragmatic, musical competence model elaborated by Stefani; and there is the inter-objective comparison elaborated by Tagg (based upon the notion of “museme”, coined by Seeger on the model of “morpheme”).

Most of these approaches do not even speak the same semiotic jargon; so that, great is the confusion under the sky of musical semiotics.

3. Side two: The intrusive influence of musicology

Musical semiotics has always been strongly tied to musicology, to its terminology, analytical tools, and ideology. We have to bear in mind that this branch of the discipline had started off with Ruwet, in the Sixties, as a method modelled upon structural linguistics to make the criteria of musicological analysis explicit and, therefore, properly scientific. As a consequence, most of musical semiotics is prominently musicological (and it is often more musicological, rather than semiotic), and score-centric; namely, it is based on the analysis of the score, it reduces music, de facto, to its notated – or transcribed, ex post – form. But the score is no more the chief way to store music (we have had analogue recordings and now we have digital ones) and today we perfectly know that notation, as the grammar, and the score, as the medium, are to music what a screenplay is to the moving images – Just a partial summary.

Once, it may have been possible to claim that “even the best equipment and the most perfect record cannot give us nothing but music ‘in a box’. The record is an important means of knowledge, but still it is a surrogate, which cannot replace the direct listening of music” (Maselli 1972: XI; my trans.). But, after the invention of the phonograph, namely after the development of a whole new sonic and musical aesthetics – which we may call timbric-acousmatic-phonographic (think of the Futurists, Varèse, Schaeffer, Chion etc.) – can we still analyze the score on behalf of music? Can we still be so incredibly unprepared to exploring the sonic richness of contemporary media?

4. Best of: The recovery of innovation (The plastic turn)

If we got an “invention of tradition” (Hobsbawm and Ranger), we have to be able to imagine a “recovery of innovation”; that is, we should be able to recovering notions and tools from our history in order to develop it further – To complete the routes. We can continue, and revive, tradition; we can still develop Greimas’ semiotic project, by extending the assumptions he has elaborated to new fields of inquiry. That would be an internal, disciplinary bricolage; using the – semiotic – available means to build up new – semiotic – ones. Our problem is the more or less “abstract” meaning of music; let’s try to recover the best available semiotic means to deal with this issue.

Structural-generative semiotics has provided a powerful tool to deal with those visual texts that seemed to question the disciplinary capability to translate them into words and analyze them. This tool is the semiotics of the plastic arts or plastic semiotics, as outlined by Greimas (1989; or. ed. 1984) and his research group within the Paris School (Thürlemann, Floch) with regard to non-figurative or abstract paintings. The plastic language emerges by analyzing a visual text with no regards to the recognition of the objects of the world (figurative language), but to its internal structure as a set of pure visible elements: shapes (the eidetic dimension), tones (the chromatic dimension), and relationships (the topological one, the disposition of the elements) – A conception strongly indebted to the phenomenological notion of “pure-visibilism” (Husserl, Merleau-Ponty); namely, the conception of the visual matter of a given work of art as something completely autonomous from the visual dimension of the tangible reality.

The plastic dimension displays a “semi-symbolic” mode of signification, ascribable to “partial correlations between the two levels of signifier and signified”; which means that the “conformity between their two levels of language [...] is recognized not between isolated elements, as with symbolic semiotics, but between categories” (Greimas 1989: 645). In Western cultures, for instance, the colour black does not stand for “death” on its own, but because the whole chromatic category – “dark vs. light” – is being invested of such an oppositional connotation; black stands for “death” because white stands for “life”, and vice versa.

Since the plastic is a transversal dimension, applicable to any matter of expression (including the domain of food and taste, cf. Marrone 2013), it is possible to identify a series of sound-specific plastic categories, as an equivalent to those identified with regard to the visual texts (cf. Ferraro 2007 ).

Such perspective has been employed as the theoretical foundation to two – very – different semiotic projects, both brilliant and, unfortunately, available in Italian only, at the moment: Valle’s (2004) and Jacoviello’s (2012). I will briefly discuss the latter case.

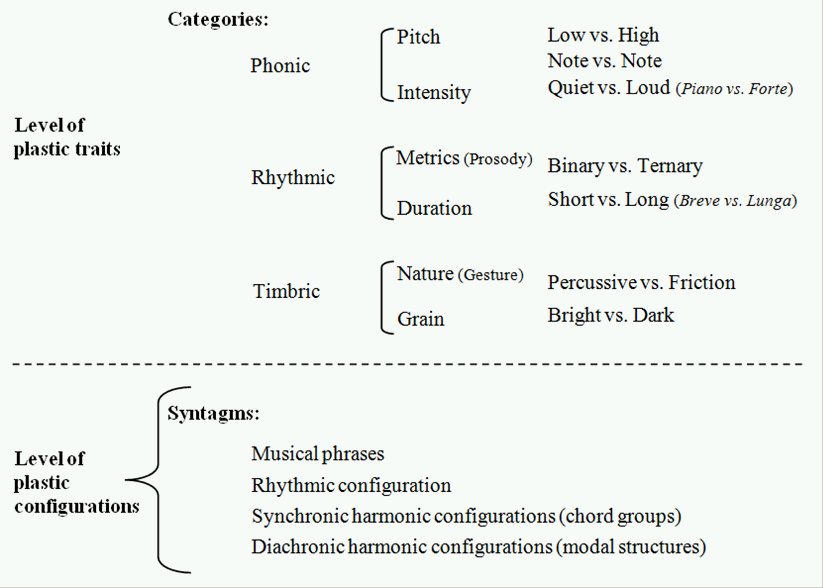

Jacoviello’s model is highly refined and articulated, being exquisitely consistent with the epistemic perspective of structuralism, and it is impossible to me here to resume it without – literally – mutilating it. But, in short: the sonic contrasts established at the plastic level of sound (e.g., low vs. high, quite vs. loud, short vs. long, percussive vs. friction, bright vs. dark), which are identified not via the score, but via direct listening (Jacoviello chooses a sonic ontology of the musical work), are both syntactic and semantic (they are meaningless, but still they already establish differences of potential meaning). Such contrasts (Fig. 1) constitute the basis of an autonomous mechanism of signification, which is not static, since it does not convey a meaning which is given “for once and for all” to the listener, but dynamic, processual, and autopoietic – The meaning in-the-listening. At the heart of Jacoviello’s model we find the “figural device” or “figural knot” (my trans.; plesso figurale in It.), namely the semiotic place wherein the plastic elements get their first traces of figurativity, yet without being substancialized, still being synergetic, synaesthetic, and multimodal – Intersemiotic, in just one word.

Figure 1. Jacoviello’s model for the plan of musical expression: the plastic level (2012: 220; my trans. and brackets).

Here you can find an attempt of synthesis of the model:

A. Plastic level: Selection of the categorical traits (phonic, rhythmic, timbric) and of the configurations of possible traits (phrases, rhythmic configurations, synchronic harmonic configurations – namely chords –, and diachronic ones – namely modes –) on the plan of expression. The contrasts between traits and configurations constitute the plastic level proper of the musical text.

B. Figural level: The differential relationships between traits and configurations define a grammar and, at the same time, a syntax of potential forms of the content, of forms of the content-to be. Thus, a “transparent” syntactic-semantic structure is being established: the figural knot.

C. Discoursive level: The figural knot is a syncretic and synaesthetic collector, being connected to the diverse semiotic domains at play (e.g., voice and music, in the genre of Opera). Such domains can be synergic or polemic one to the other; namely, they do not necessarily convey the very same meaning (e.g., the case with a song featuring a “happy” music, but “sad” lyrics). The objects of the external world start to emerge from the figural knot before and beyond their precise, specific iconic content. The investment of value of figural density is a process which is all internal to the differential and processual logic of the musical text, without any reference to any external, pre-constituted musical nor cultural form.

To one who is familiar with the structural-generative tradition, and who has already experienced the efficacy of plastic semiotics with regard to visual texts, Jacoviello’s model sounds like a Columbus’ egg: A very refreshing, logical, and “natural” solution to many epistemological and theoretical problems affecting the discipline in its confrontation with sound and music (although it is not an easy job to be accomplished at all, as regards the concrete analysis of a single piece of music).

5. Bonus track: Sampling, remixing, and remaking semiotics itself

With a focus on the – actual or potential – mediated nature of any post-1877 music (the year Edison invented the phonograph), I myself have tried to develop the model further (Marino 2015). I have added a proper topological category to the paradigm of the sonic plastic ones indicated by Jacoviello (recovering it from the original Greimassian proposal); I have elaborated a basic theory for the phonographic enunciation (which I will briefly, and partially, discuss here); a model for the musical figures (recovering the Taggian notion of “museme”, and connecting it to Gibson’s “affordance”); and a theory for the musical competence (heavily drawing inspiration from Stefani’s).

I recovered the enunciation theory as re-elaborated by Metz with regard to film (1991), and the consequent semiotic debate (Fontanille, Odin, Casetti, Eugeni), integrating it with the narratological categories proposed by Genette (1972; Eng. trans. 1980). By recovering Metz’s “impersonal enunciation” (an enunciation meant not to be anthropomorphic nor deictic, but meta-discoursive and self-referencing), it is possible to consider the acousmatic sound as producing a kind of “phonographic shot”, within which it is possible to employ the narratological categories elaborated with regard to literature and films – Not only the category of voice (time of narration, diegetic level, and persona), but also that of mode (the distance, or the issue of “playing vs. making-you-listen”, and the perspective, or the issue of the “point of listening” or “aural focalization”, in our case).

I have recovered from Metz’s filmic theory also the distinction between “prosonic materials” (natural sound, which can be recorded and manipulated) and “phonographic language” (sound effects and manipulated sound). It is possible to distinguish between an “aesthetics of recorded sound” (a past sonic event has been recorded and is being re-presentified – made present again – via the recording) and an “aesthetics of acousmatic sound” (a kind of music that does not want to be perceived as the account of something already happened, but that occurs, that happens, live, just when the sound comes out from the speakers or through the headphones). By adapting a typology elaborated by Casetti (1986), originally concerning filmic language, I ended up in proposing a four-folded typology of enunciation modes for mediated or phonographic music:

A. Objective shot: I – the phonographic shot – present myself to you, listener, as the account of sonic events that have occurred in a past moment (pretending to be a transparent glass, I am the faithful recording of that thing). This fits the aesthetics of recorded music, with a strong prominence of prosonic materials.

B. Direct interpellation: I – the phonographic shot – present myself to you, listener, “through the looking glass”, and I “talk” to you (just like in the “apostrophe to the Reader” or in a voice-over segment of a movie) thanks to the lyrics or “telling you about some other music” (all the degrees of intertextuality). This is a kind of enunciated enunciation on the plan of prosonic materials (typically, within a “recorded music” situation).

C. Subjective shot: I – the phonographic shot – present myself “on this side of the mirror”, being a sonic event that occurs, that happens here and now, admitting you, listener, in the world of sounds as such. This fits the aesthetics of acousmatic music (prominence of phonographic material; so-called Schaefferian “reduced listening”). As regards the passages of concrete music inserted into Pink Floyd’s Alan’s Pyschedelic Breakfast (Atom Heart Mother, 1970), Spaziante (2009: 288) talks of a kind of “sonic subjective shot” (my trans.).

D. Unreal objective shot: I – the phonographic shot – present myself to you, listener, as the result of a process of recording, as acousmatic music in-the-making; namely, I show you myself “in the mirror”, displaying all my internal mechanisms of functioning, the difference, the friction between prosonic (natural sounds, recorded) and phonographic (manipulated sounds). This is a form of enunciated enunciation on the plan of phonographic materials. As regards the “radio-switch” effects featured in the songs produced by Uwe Schimidt/Atom Heart under the moniker Señor Coconut y su Conjunto (with particular reference to the record El Baile Alemàn, 2000), Spaziante (2007: 57-58) talks of “meta-music”, “sonic mise en abyme”, and “trompe-l’oreille”.

The typology is highly perfectible but, still, it is a good starting point. And it just came out from a bricoleuse scrutiny of our generous literature.

6. Outro

In this short essay, I just wanted to show that our tradition, the tradition of semiotics, is so rich to the extent that it has not been fully explored and employed yet, being fertile and up-to-date. On the one hand, we do have to be always “scientifically awake” but, on the other, we do not need to constantly be in the wake of the latest scientific discovery. We do not need, say, to import “mirror neurons” from neo-cognitive, positivist, and ontological approaches into our field, squeezing them into our epistemology, in order to go further with our job as semioticians. The fact that we know how our brain works (at least, better than some years ago, and constantly getting a more and more precise picture) does not exhaust our horizon of research and our search for meaning at all – It may be just a point of departure, not our final destination.

7. Credits: Acknowledgments

The Author would like to thank Kristian Bankov, Eero Tarasti, and Stefano Jacoviello.

References

(All online resources were last accessed Jan. 31, 2015)

CASETTI, Francesco. 1986. Dentro lo sguardo. Il film e il suo spettatore. Bompiani: Milano.

CASTELLANA, Marcello. 1986. “Musicale (sémiotique)”. In Algirdas J. Greimas & Joseph Courtés (eds.), Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, II. Compléments, débats, propositions, 147-148. Paris: Hachette.

FERRARO, Guido. 2007. “Raccontare la perdita del senso. Per un’analisi della musica dei King Crimson”. In Patrizia Calefato, Gianfranco Marrone & Romana Rutelli (eds.), Mutazioni sonore. Sociosemiotica delle pratiche musicali, E/C monographic issue, 1: 21-29. Nuova Cultura: Roma. URL http://bit.ly/ECMutazioni2010 .

GENETTE, Gérard. 1972. Figures III. Éditions du Seuil : Paris.

GREIMAS, Algirdas J. 1989. “Figurative Semiotics and the Semiotics of the Plastic Arts”. In New Literary History, 20(3): 627–649. URL http://bit.ly/Greimas1989.

JACOVIELLO, Stefano. 2012. La rivincita di Orfeo. Esperienza estetica e semiosi del discorso musicale. Milano-Udine: Mimesis.

MARINO, Gabriele. 2015. Suoni di un futuro passato: per una sociosemiotica del dubstep. Dinamiche nel sistema dei generi e discorsi sulla ‘novità’ nella popular music contemporanea. Ph.D. dissertation: University of Turin.

MARRONE, Gianfranco. 2013. “Livelli di senso: dal gustoso al saporito”. In Paolo Leonardi & Claudio Paolucci (eds.), Senso e sensibile. Prospettive tra estetica e filosofia del linguaggio, E/C monographic issue, 17: 128-136. Nuova Cultura: Roma. URL http://bit.ly/Marrone2013.

MASELLI, Gianfranco. 1972. Il Cercadischi. Guida alla formazione di una discoteca dal Medioevo ai nostri giorni. Mondadori: Milano.

METZ, Christian. 1991. L’énonciation impersonnelle, ou le site du film. Paris : Klincksieck.

MONELLE, Raymond. 1992. Linguistics and Semiotics in Music. Harwoord Academic Publishers: Newark, NJ.

SPAZIANTE, Lucio. 2007. Sociosemiotica del pop. Identità, testi e pratiche musicali. Carocci: Roma.

SPAZIANTE, Lucio. 2009. “Come dire cose senza parole: figuratività sonora e sound design, tra musica e cinema”. In Maria Pia Pozzato & Lucio Spaziante (eds.), Parole nell’aria. Sincretismi fra musica e altri linguaggi, 285-295. ETS: Pisa.

TARASTI, Eero. 2002. Signs of music. A guide to musical semiotics. Mouton De Gruyter: Berlin-New York.

VALLE, Andrea. 2004. Preliminari ad una semiotica dell’udibile. Ph.D. dissertation: University of Bologna. URL http://bit.ly/Valle2004.