TAKING A STEP OUTSIDE THE PHOTO AND FRAME: HOW SHOULD DRAWINGS BE ANALYSED IN THE CONTEXT OF GEOGRAPHY EDUCATION?

University of Helsinki, Finland

markus.hilander@helsinki.fi

Abstract

The combination of geography and semiotics seems to be rather rare. Nonetheless, geography as a discipline has always been visually oriented because of the usage of maps. However, geographers tend to be interested in the final meanings of visual representations rather than the processes during which the meanings are being produced. To approach these processes, we printed a photo taken in New York City (2008) on an A3-sheet and asked in total 64 Finnish high school students to draw around the photo. Next step of our study is deciding in which ways we are to analyze the drawings in question; during our presentation, we hope to gain new ideas from the audience to approach our data-set.

In the 1970s, Roland Barthes stated that connotations are likely to be important in semiology. He continued that connotative phenomena have not yet been systematically studied. In addition, a Finnish researcher, Virpi Blom, has said that the analysis of connotation is in the heart of interpretation. When it comes to the drawings we have collected, we can, for example, focus on what sorts of connotations the students have drawn. In her book, Decoding Advertisements, Judith Williamson approaches advertisements both as signifieds and signifiers. The same division can be used for drawings as follows: when the photograph itself is the signifier, the drawing is dominated by the photo; instead, when the drawing is the signifier, the drawer abandons the ready-made signified (the photo), and a semiotic act will take place. The former example is to do with synecdochal signs, the latter with metonymic signs. When it comes to visual literacy and semiotics, iconicity, indexicality, and metonymic signs are said to be the most important aspects we should concentrate on. It was Barthes who said that there is an abundant literature on metaphor, but next to nothing on metonymy.

In addition, there are other interesting findings in the drawings; one, for instance, is whether the students have drawn people in their city landscape or not. It seems that quite often people are not drawn. Is it because of a human being is somewhat difficult to draw or do youngsters really not consider people to be part of an urban landscape?

1. Introduction: A drawing task

The combination of geography and semiotics is rather rare. Nonetheless, geography as a discipline has always been visually oriented because of the usage of maps. Therefore, geography has much to do with signs, as well as communication and the difference between illusion and reality (Cobley 2010: 3); maps and their coordinates work as indexes locating places on the globe. However, geographers tend to be interested in the final meanings of visual representations rather than the processes through which the meanings are produced. To approach these processes, a photo taken by Markus Hilander (2008; see Figures 1 and 2) in New York City was printed on an A3-sheet and a total of 64 Finnish high school students were asked to draw around the photo. In addition, members of the audience of the presentation at the World Congress of Semiotics in Sofia, Bulgaria were asked to draw their mental images. Once a researcher has collected a visual data-set, many questions must be faced about the ways in which to approach it. The next step of the research was to make a final decision about how to analyse the drawings collected.

The present plan is to examine the idea of punctum by Roland Barthes (1981) and his “blind field” (champ aveugle); that is, to consider the surroundings of a photo that have been cut off from the photo itself (Knuuttila 2007: 49). If we should draw our mental images around a given photograph, what sort of signs would those drawings be? To what extend would these drawings explain and give meanings to the photo itself? The instruction for the high school students and the audience in Sofia was as follows: “What sort of things and mental images do you relate to the photo? Imagine you could expand and/or continue the photo and the landscape it depicts by drawing around the photo”.

In this methodological paper, two concepts to conduct a content analysis of the drawings are introduced. As a geographical way of approaching the drawings, the “development compass rose” that is introduced in literature of didactics of geography (e.g., Lambert, Morgan, and Swift 2004) is used. Likewise the four principal compass points, elements in the drawings are sorted into four domains: natural, social, political, and economic. Eero Tarasti also finds four cases in his “Z model” that are used as a semiotic way of interpreting the drawings. Tarasti’s categories are as follows: body (M1), identity and personality (M2), social roles and institutions (S2), and norms and values (S1). The final aim of the research project will be opening up what sorts of information can and cannot be reached with these analytical tools.

Next, the photos and drawings are examined as two types of connotations: signifiers and signifieds. Then, the development compass rose and the Z model will be introduced and it will be demonstrated how they could be used as vehicles for an analysis. For illuminating the models, two examples of the drawings made by the audience of the presentation in Sofia will be submitted.

2. Two types of connotations

In the 1970s, Barthes (1977: 85) stated that connotations are likely to be important in semiology. He continued that “[c]onnotative phenomena have not yet been systematically studied” (Barthes 1977: 90). Furthermore, a Finnish researcher, Virpi Blom (1998: 212), has said that the analysis of connotations is at the heart of interpretation. When it comes to the drawings that have been collected, it is possible to focus on what sorts of connotations the students and the audience of the presentation have drawn. In her book, Decoding Advertisements, Judith Williamson (1978: 31–36) approaches advertisements as both signifiers and signifieds. The same division can be used for the drawings. When the photograph itself is the signifier, the photo dominates the drawing; on the other hand, when the drawing is the signifier, the subject abandons the ready-made signified (the photo), and a semiotic act will take place (Tarasti 2000: 139). Photographs depict only a part of the landscape by the pars pro toto principle; this makes photos metonymic signs (Knuuttila 2007: 47). In visual literacy teaching, icons, indexes, and metonymic signs are emphasised as the most important aspects (Seppänen 2008: 191). Barthes (1977: 61) said that “there is an abundant literature on metaphor, but next to nothing on metonymy”.

2.1. The photograph as signifier

Williamson (1978: 31) states that a “product, which initially has no ‘meaning’, must be given value by a person or object that already has a value to us, i.e., already means”. Therefore, the product being advertised—or as in this research, the drawing—is the signified, and the correlating thing is the signifier (Blom 1995, 8: 17–18). In a case where the photograph’s elements continue smoothly to the drawing, the drawing is dominated (d-ed) by the photograph; hence, the photograph is the signifier (Tarasti 2000: 139). In Figure 1, the printed photograph depicting the city of New York with people, cars, and skyscrapers can be seen. On the right side of the photograph, there is half a building, which the subject has completed leaving the left side totally blank. Gillian Rose (2012) says that these sorts of signs, or connotations, are synecdochal signs. She writes that this “sign is either a part of something standing in for a whole, or whole representing a part” (Rose 2012: 121). There is an advertisement for a Finnish shipping company that is a good example of a synecdochal sign; even though only the letters NG LI can be seen, Finns will understand that the letters stand for Viking Line (e.g., Hilander 2013).

Figure 1. Drawing by a 27-year-old woman from Brazil

2.2. The drawing as signifier

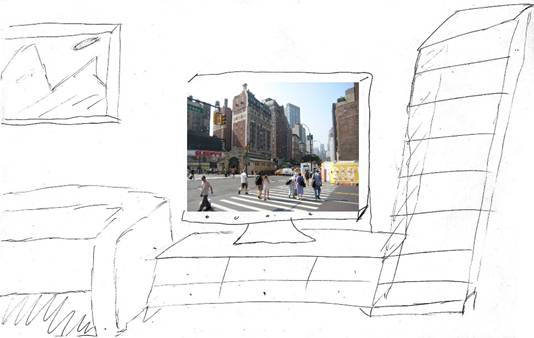

When meanings are transferred to the product from other objects that co-exist in the advertisement, the product itself comes to mean. The product becomes the sign itself, the signifier, which gives meanings to its surrounding elements and events (Williamson 1978: 34–36; Blom 1995, 8: 18–20). The product, or the drawing, now has the power; it becomes the dominant (d-nt) (Tarasti 2000: 139), whereas the role of the photograph is reduced to a signified. In Figure 2, the subject has implemented a semiotic act and abandoned the ready-made signified; he has drawn elements, such as a television, a shelf, and a sofa, that do not have much in common with the urban landscape depicted in the photo. Rose (2012: 120) calls these kinds of connotations as metonymic signs; it is something associated with something else, which then represents that something else. In this case, the drawing explains the photograph’s connotations by filling the blind side with the subject’s own ideas, thoughts, and mental images. Next, the development compass rose and the Z model are introduced and Figures 1 and 2 analysed more in depth.

Figure 2. Drawing by a 46-year-old man from Greece

3. The development compass rose

The four domains that the development compass rose encourages the viewer to attend to and explore the links between are natural, social, political, and economic. A teacher or a researcher can place an image, an issue, or a phenomenon in the centre of the compass. A range of questions about the place and situation that the photograph re-presents (see, Conclusion) can be generated for each of the four compass points. These can then be compared with questions generated about an apparently different situation, and the commonalities between them explored (Tide global learning 2014: n.p.). The domains are:

(1) Natural domain: These are questions about the natural as well as the built environment: energy, air, water, soil, living things, and their relationships to each other.

(2) Social domain: These are questions about people, their relationships, their traditions, culture, and the ways in which they live. It includes questions about how gender, race, class, and age affect social relationships.

(3) Political domain: These are questions about power, who makes choices and decides what is to happen and who benefits and loses as a result of these decisions and at what cost.

(4) Economic domain: These are questions about money, trading, aid, ownership, buying, and selling.

In Figure 1, there are no elements of the natural environment drawn; only the built environment in a form of skyscrapers is present (natural domain). At the same time, the skyscrapers indicate wealth and money (economic domain). In addition to the natural environment, people are also excluded from the drawing (social domain). However, private motoring can be interpreted as a cultural feature; perhaps the subject imagines that people are inside the cars and buildings (see, Hilander 2012: 221). The non-visible people could be local because they are driving their own cars; vehicles drawn have not been marked as public transport or taxes.

In Figure 2, the natural environment is present in the form of a painting with mountains (natural domain). The television and other furniture—a sofa and a shelf—imply the wealth of the resident (economic domain). However, the drawing does not give any hints about where in the world the apartment might be located (social domain).

4. The Z model

In his theory of existential semiotics, Eero Tarasti introduces the Z model. It discovers the movements between the subject and the society. Tarasti (2012: 328) refers to the subject by a French word Moi and to the society by Soi that means “the subject observed by others”. With his theory, Tarasti (2012: 316) takes part in philosophical and methodological discussions of signification conceived in the 2010s; that is, he aims for what is called “neosemiotics”. However, this paper will not concentrate on the philosophical background of the model (see, e.g., Tarasti 2012). Tarasti (2012: 330) calls his model a “Z” model considering its inner motions between four categories. In order to conduct a content analysis of the drawings using the Z model, the four categories must be taken as independent entities. They are:

(1) M1: This represents the ego and the body, which appears as kinetic energy, desire, and gestures. The ego is not yet conscious of itself, but rests in the naive Firstness of its being.

(2) M2: This is the category in which the mere being of the subject becomes existing, as in Peirce’s Secondness. Ego discovers its identity, personality, and reaches a certain kind of stability or permanent corporeality via habit.

(3) S2: This is about societal and institutional practices. It consists of applied values, choices, and realizations from S1.

(4) S1: This is an abstract category that refers to norms, ideas, and values, which are purely conceptual and virtual; they are potentialities of a subject, which can either be actualized or not into S2.

In Figure 1, M1 and M2 categories are not present because there are no people drawn in the picture. The subject has continued the pedestrian crossing, which can be taken as a moral sign of S1; for instance, cars are not permitted to drive over people. The crosswalk could also be interpreted as a recommendation for walking. Private motoring tells something about values (S1) and pollution. Moreover, as a daily practice, private motoring can be linked to S2.

In Figure 2, the subject has drawn a painting with mountains that can remind some people of leisure: hiking, travelling, and downhill skiing. These activities are related to body, and, therefore, to M1. The apartment’s interior decoration with the television, sofa, and shelf—that is, incidentally, depicted as tall as the skyscrapers in Figure 1—describes the dweller’s personality (M2). The furniture also hints that the dweller has enough money to buy them (S2). However, the viewer cannot know if the dweller is watching a documentary about New York City voluntarily or forced (S1).

In summary, there are at least two differences in the results depending on which one of the models is used in the content analysis. Firstly, when using the Z model, M1 and its body trigger the viewer to think about the meanings of the painting with mountains in Figure 2. Does the subject or the potential apartment dweller like downhill skiing? If so, is the subject or the dweller more of an outdoor person than indoor person? Does the subject or the dweller live in a city or in the countryside? Answers to these questions depend on where in the world the subject or the possible dweller lives. The background information tells us that the subject is from Greece; the largest ski resort in Greece is close to Athens. However, it might be more intriguing not to consider the lifestyle of the drawer himself, but to determine how the drawing explains the photo and its meanings. In this approach, there is a profound juxtaposition, or a binary, of natural and urban landscapes in Figure 2. In the context of the drawing and the photo, it seems that the documentary about New York City on television is more exotic than the painting and all the possible outdoor activities to which it refers, because the painting on the wall is in sight round-the-clock, whereas the documentary lasts only for a while. However, one could argue that the apartment itself in the picture indicates the busy life of a citizen rather than a life spent in the countryside. In addition, mountains can also be associated with other things than just outdoor activities, for instance, with danger and the unknown, or climate change.

Secondly, the meaning of the pedestrian crossing, in Figure 1, would not stand out if the development compass rose had not been satisfied. The pedestrian crossing could be associated with the third domain of the compass, that is, the political domain and its decision-making dimension. However, the crosswalk as a punctum was not revealed until using the Z model. It was specifically the S1 category that suggested the ways in which figure 1 expresses values and norms.

5. Conclusion: What is the source of meanings in the photo?

Comparison of different methods can be useful and advantageous as long as the aim is not solving which one of the methods is the best. Instead, the aim should be to deepen the interpretations with the help of different views and perspectives that the various methods provide (Rakkolainen and Ehrling 2010: 347). In a case where the researcher uses pre-existing codes, the research can be called “etic” derived research. Based on the very limited experience of using the development compass rose in this paper, this might be called etic research. The four domains – natural, social, political, and economic – appear somewhat stiff and inflexible as a tool for content analysis. With the compass points and their questions, it is difficult to see beyond the drawings and their elements into the meanings.

When the researcher allows the data-set to represent, the research is based on the “emic” viewpoint, that is, the viewpoint of the interviewee, informant, or the data-set (Rakkolainen and Ehrling 2010: 326–327). The name of the Z model is an abbreviation for Zemic model; “Z” describes the motion between the four categories and “emic” refers to the fact that the movement takes place within the model (Tarasti 2012: 330). The inner motion of the model is thus included in the name itself. From this perspective, the Z model helps in considering the elements drawn in a wider and more complex way than the development compass rose allows. Nonetheless, both models produce different sorts of information that complement each other.

One must keep in mind that the data-set introduced here is very minimal. The audience of the presentation in Sofia gave us in total 11 drawings and only two examples of those are given in this paper, because the aim was not to introduce finished research results, but to discuss different options for conducting a content analysis. However, according to the outcomes of the development compass rose and the Z model regarding the two drawings, slight differences can be noticed. The former seems to lean more on the expectations of the viewer and the researcher, whilst the latter gives an opportunity to stay open to the data-set helping the researcher to engage in the drawings made by young people. This is very welcome in geography education where the aspects of everyday life of young people are increasingly significant (Tani 2011).

In addition, there are other interesting aspects to search for in the drawings, such as the presence or absence of people. It seems that quite often people are not included in the drawings. Is this because a human being is somewhat difficult to draw or because people are not considered to be part of an urban landscape? In the photo of New York City, there is also one geographical hint on the upper left corner regarding the location where the photo has been taken. Unfortunately, neither one of the subjects paid attention to the tip leaving the [Bro]adway sign uncompleted.

It is desirable that a researcher does not think that the research is finished after the process of coding the data-set. The next step is to analyse and interpret the coded data-set and answer the research questions. In this study, the question was asked what sort of information it is possible to gain with the different methods on which content analysis is built. The bigger picture, or a research task, is as follows: because a photo never completely presents the world, that is, it can never present the world objectively, does it thenre-present the worldview of the photographer or the viewer?

References

BARTHES, Roland. 1977. Elements of Semiology. New York: Hill and Wang.

BARTHES, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida. New York: Hill and Wang.

BLOM, Virpi. 1995. Farmarimainoksen väitelauseet [Levi’s and its propositions in an advertisement]. Lähikuva 8(4). 9–23.

BLOM, Virpi. 1998. Onko mainoksella merkitystä? Mainosten tulkinta Roland Barthesin koodiston avulla [Does an advertisement matter? Analysing advertisements with the help of Roland Barthes’ codes]. In Anu KANTOLA, Inka MORING & Esa VÄLIVERRONEN (eds.), Media-analyysi. Tekstistä tulkintaan [Analysis of media. From text to interpretation], 200–228. Lahti: Helsingin yliopiston Lahden tutkimus- ja koulutuskeskus.

COBLEY, Paul. 2010. Introduction. In Paul COBLEY (ed.), The Routledge Companion to semiotics, 3–12. London and New York: Routledge.

HILANDER, Markus. 2012. Nuorten piirustukset maantieteellisten mielikuvien ilmentäjinä [Young people’s drawings and mental images in geography]. Terra (124)3, 218–221.

HILANDER, Markus. 2013. Semiotiikka kuvien maantieteellisen tulkinnan mahdollisuutena [Semiotics as an opportunity for interpreting photos in geography].http://www.ays.fi/versus/pdf/versus_3_5.pdf (last accessed: 20 November 2014).

KNUUTTILA, Sirkka. 2007. Barthes ja punctumin peitetty mieli [Barthes and the hidden mind of punctum]. In Harri VEIVO (ed.), Vastarinta resistanssi. Konfliktit, vastustus ja sota semiotiikan tutkimuskohteina [Rebellion resistance. Conflicts, protest, and war as research objects in semiotics], 33–53. Helsinki: Palmenia & Yliopistopaino.

LAMBERT, David, Alan MORGAN & Diane SWIFT. 2004. Geography: the global dimension. Learning skills for a global society. London: Development Education Association. www.geography.org.uk/global (accessed 17 December 2014).

RAKKOLAINEN, Maria & Leena EHRLING. 2010. Motivoivan haastattelun analyysi kahdella eri menetelmällä [Analysing motivational interviewing data with two different methods]. In RUUSUVUORI, Johanna, Pirjo NIKANDER & Matti HYVÄRINEN (eds.), Haastattelun analyysi [Analysing interview data], 325–350. Tampere: Vastapaino.

ROSE, Gillian. 2012. Visual methodology. An introduction to researching with visual materials. London: Sage.

SEPPÄNEN, Janne. 2008. Katseen voima [The power of eye]. Jyväskylä: Gummerus.

TANI, Sirpa. 2011. Is there a place for young people in the geography curriculum? Analysis of the aims and contents of the Finnish comprehensive school curricula. InNordidactica 1(1), 26–39.

TARASTI, Eero. 2000. Existential semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

TARASTI, Eero. 2012. Existential semiotics and cultural psychology. In Jaan VALSINER (ed.), The Oxford handbook of culture and psychology, 316–343. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

TIDE GLOBAL LEARNING 2014. http://www.tidec.org/sites/default/files/uploads/2c.50%20Compass%20rose.pdf (last accessed: 17 December 2014)

WILLIAMSON, Judith. 1978. Decoding advertisements. Ideology and meaning in advertising. Singapore: Marion Boyars.