FRANZ LISZT – A DILEMMA OF STYLISTIC INTERFERENCES

University of Arts “George Enescu”, Iaşi, Romania

mihaela.balan87@yahoo.com

Abstract

Considered both as a national and a universal artist, Franz Liszt has inflamed a deep process of continuous progress and radical changes in music, on every level he has undertaken: piano playing, composition, conducting and writing about music. He remained in the history as a complex musician, with a rich activity, maybe the most visionary composer at that time, because his personality was so controversial, that he literally shocked his contemporaries in every parameter of his art. There are numberless books, biographies, treatises, studies, dissertations about his activity, written in different manners and using various analysis techniques. The purpose of this paper is to go beyond some texts where Franz Liszt was approached as one-sided figure, in order to outline his personality as a whole, by pointing some key-elements in his artistic psychology, some deep resorts of his composing principles. In this regard, I have chosen some well-known authors who wrote about Liszt and have kept the most representative elements of their works to describe him, trying to ‘catch’ the essence of the great Franz Liszt.

1. Introduction – Franz Liszt’s position among the 19th composers in the History of Music

Tradition, especially innovation, elevating idealism and revolutionary spirit - in one word, we are speaking about genius. These are some terms that might summarize the aesthetics of the 19th century, with reference to that great artist considered the soul of Romanticism, a man completely devoted to his generation and its ideals. His name was Franz Liszt.

Equally considered a national and universal artist, Franz Liszt has inflamed a deep process of continuous progress and radical changes in music, on every level he has undertaken: piano playing, composition, conducting and writing about music. He remained in the history as a complex musician, with a rich activity, maybe the most visionary composer at that time, because his personality was so controversial, that he literally shocked his contemporaries in everything he did. Because of the nature of this work, we can’t raise an innovative, unheard or spectacular point of view on Franz Liszt’s personality. He became, in time, a true legend in the history of music. He was approached in countless books, biographies and studies from different angles, in order to be described with respect to his amazing life, his polyvalent activity, or his romantic psychology - which was considered to be a controversial spirit.

He was described in different manners: technically, analytically, metaphorically, philosophically and so on. We will offer some examples: ‘magnetism’ and ‘electricity’ by Heinrich Heine, ‘a gifted joker’ by conductor Hermann Levi, ‘nice and generous, arrogant and whimsical’, with a ‘kinetic music, meant to amaze, to astonish’ – as wrote Harold Schonberg, ‘apparent humbleness’ – in the famous caricature and cartoon magazine from Paris Le Charivari[1], ‘gallantry of a knight’, ‘tendency towards splendour and declamation’[2] – by Romanian musicologist Eugeniu Speranţia, ‘a piano sorcerer’[3] – by Ioana Ştefănescu, ‘sulphurous greatness’ – by Charles Rosen, etc. All these attributes reflect the malicious curiosity of his contemporaries and also the attempt of the generations to come to ‘catch’ his being. He was envied, discussed and he became the subject of many intrigues, polemics around his existence. Unlike his older music colleague Niccolo Paganini, whose destiny gave birth to different Mephistophelian legends (fed by the violinist himself), Liszt chose a clear, rational way of being, organized according to his native impulses and to his huge responsibility for his artistic gift. Beyond every calumny and gossip about him, Liszt had a precocious wisdom, being conscious of the high meaning of his endowment. This is why he has invested a great quantity of physical and inner energy in order to promote the young gifted players, composers, writers, but with no financial resources or wealthy connections.

The spreading of his talent and his music, his European success are due to his career developed in the main artistic centres, because Liszt was, at a high level, a ‘vagrant’ musician, a passionate traveller, always wanting to meet new people. We would like to quote some observations made by a famous radio and TV producer, referring to Liszt’s permanent willing to meet and conquer the unknown: ‘artist having the great delight of travelling’, ‘a musician who knew that all the roads towards us pass around the globe’, ‘a seismometer of his century, a musical guide of Europe’.[4]

2. Franz Liszt approached by musicologists

Among the few musicologists who have emphasized the nature of Liszt’s genius were Béla Bartók and Emil Haraszti. If Bartok is notorious in the history of music, Haraszti must be introduced as a Hungarian historian and critic of the first half of the 20th century, interested in composers such as Chopin, Liszt and Bartok. Haraszti has written many studies and specialised papers focused on biographic elements essential for their evolution, specific language features shaped on the background of national conscience belonging to the native place. Bartok has found the palliating circumstances for the frequently called ‘exaggerated Romantic pathos’ in the context of the period that reached its pinnacle, while Haraszti has emphasized the influences assimilated by Liszt during his studies and journeys through the entire Europe. Thus, the German School (represented by Robert Schumann, Richard Wagner, Johannes Brahms), the French Culture (Hector Berlioz, Frederic Chopin, César Franck, Camille Saint-Saëns), the Italian School (with its main composers representing the specific bel-canto: Gioacchino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, Vincenzo Bellini, Giuseppe Verdi) and the Russian School (to whom he had some connections, yet more distant and formal), all these cultures have determined the evolution of the Hungarian composer. Thus, Liszt has developed himself by constantly relating his ideas and principles to the romantic context of his contemporaries.

A very important musicologist of the 20th and 21st centuries is Serge Gut, author of many important works, studies, papers focused on musical language from the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century. He is well known for his particular concern in Franz Liszt’s personality, considering that his stylistic influences can be divided into two categories: general and musical. One has to take into consideration the fact some interference[5] didn’t have a major impact on his aesthetic orientation, but offered him some reference points in order to find his own path among his predecessors and contemporaries, in the general context of the history of music. There are many contradictory perspectives on Franz Liszt’s origin, because of his birth place, his studies in different musical centres, his settlement on short or long term in different places, which led to the claiming of different European countries regarding his stylistic affiliation. As Serge Gut concludes, this fact has a less significance than the entire variety of the mentioned interferences.

From this point of view, it is important to mention the influence (and not only the interference) of the Hungarian Gypsies. This matter also raised many polemics about the priority of gypsy elements compared to the Hungarian, national things, or the opposite. Liszt has been particularly attracted to the gypsy music from Hungary, even if he got into contact with many other national contexts of gypsies from abroad. In his book Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie, Liszt explains three main ideas:

1. The musical art common to gypsies and Hungarians, related to their Asian origin.

2. The anteriority of the gypsy music

3. The superiority of the gypsy music[6]

Serge Gut used some quotes from Liszt’s ideas referring to his Hungarian Rhapsodies, which were named after the ‘epic’ element inside the melody inspired by Hungarian folk songs, leading to the unity and the coherence of all works entitled similarly. ‘Hungarian people adopted gypsies, who became national musicians. Thus, Hungary might claim with good reason the paternity of this art, nourished with its own wheat and vineyard, raised under the sun and close to the shadow of Hungarian trees. Their music is related to the most glorious historical events of their homeland and to the most intimate memories of every Hungarian inhabitant.’[7]

From the purely musical point of view, one can find elements specific to gypsy music which can be observed in Franz Liszt’s work:

• the gypsy scale (having two augmented seconds)

• the rhythm, originated from a gypsy dance named verbunkos, usually played during Napoleon’s campaigns;

• melisma and different ornaments, frequently overloaded (leaning notes/ appoggiaturas, grace notes, échappé notes, repeating chords on great rhythmic values or very short durations.

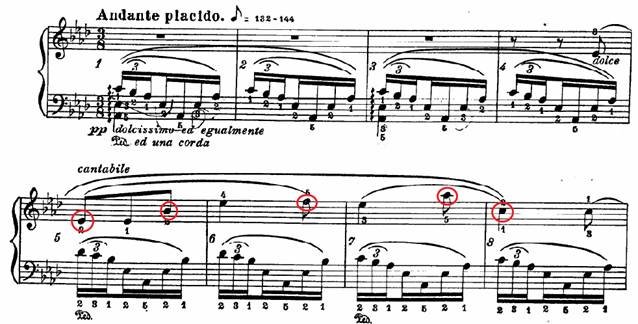

Example 1 – Franz Liszt – Hungarian Rhapsody no. 2, ms. 1-8

3. Liszt – pianist and composer

The first feature that assessed Liszt in the glorious height of European culture was his pianistic virtuosity. Among his predecessors, W. A. Mozart was firstly a musician and secondly pianist, unlike Muzio Clementi who was in the converse situation; among his contemporaries, Robert Schumann wished to become a great pianist, but the circumstances of his life led his career towards composition and musical critics, while Frédéric Chopin was an exceptional pianist, a very appreciated pedagogue, but all these activities had an ordinary function – to ensure his daily income, because his deepest aspirations were focused on musical composition. Franz Liszt is a particular case among the virtuosos of the 18th and 19th centuries, being considered unanimously a genius of piano playing. While playing, he proved to be a very talented interpreter of the musical meanings, a creator of new significations and a gifted pianist. ‘Liszt was the first to understand the dramatic and emotional meaning of new instrumental techniques (around 1830), accomplishing one of the greatest revolutions in the music created for keyboards until that moment of the history. He configured what would later become pianistic romantic sonority.’[8]

There were also many discussions concerning Franz Liszt and Niccolo Paganini as similar cases from the artistic point of view. Even if the pianist was inspired by the fascinating violin technique mastered by Paganini, who cultivated in him the strong desire of transposing the principles of ‘acrobatic’ virtuosity in the pianistic art field, this influence did not expand to the level of compositional general principles. Compared to Paganini, Liszt had a much larger amount of works and personal strivings that had nothing to do with his purpose of remaining in history as a victim (or winner?) of a Mephistophelian pact. Liszt used his talent in different manners and for different purposes: in the first part of his life, he aimed towards becoming famous, searching for success, recognition in the entire Europe of his brilliant talent, and later, after reaching a certain level of artistic maturity, he focused his energy on helping others and devoted himself to altruistic principles.

Franz Liszt also had some personal qualities concerning his social attitude, which brought him in the centre of the political scene, becoming in some of his European tours, a potential risk factor for the imperial doctrine. The public all over Europe became part of a transcendental musical experience while seeing him playing in his innovative eccentric manner. Even if Liszt hasn’t expressed himself directly upon political views or perspectives, he inspired his audience towards freedom and independence only by his way of being, playing and composing. Anyway, he became a political man after the middle of the 19th century, and he became a point of interest for Austrian governmental authorities, who supervised/watched him closely during his entire tour in Hungary in 1846.

Freedom, the symbol of many romantic ideals, was suggested to his public on many ways and levels:

1) Franz Liszt had a particular attitude on the stage, characterized by bravery, gallantry, natural exteriorising of his artistic feelings expressed by large gestures, which involved not only hands and forearms, but also shoulders, feet and centre of gravity. Liszt entitled his apparitions ‘musical soliloquims’ and he characterized himself as it follows: ‘Bored by the war and unable to conceive a programme to make sense, I have dared to plan concerts by myself, making fun of his famous quotation, as an artistic parody: “Le concert, c’est moi!”...’[9]

2) Another way of expressing freedom was the content of his works: Liszt transposed into music literary ideas, poetic feelings, promoting programme music. The freedom to choose a certain literary resource of inspiration allowed him a boundless imagination, where the musical programme had a suggestive function. Unlike Berlioz, who followed the narrative stages in all his works, Liszt was interested in ‘catching’ the essence of his initial idea, using a generalizing programmatism. He didn’t evoke either narrative details or complex features of depicted characters, but he rather emphasized the essential line of the dramatic conflicts. In other words, he evoked the general in particular images.

3. The artistic freedom is obvious on the structural level: on one hand, in traditional forms, inherited from previous centuries and later transformed according to expressive needs of the work (examples: sonata as a macro-form of the genre, programmatic symphony, concerto-poem conceived as a continuous movement, unified through cyclic themes); on the other hand, there were new musical genres and architectures freely structured, according to individual composing criteria (symphonic poem, rhapsody, ballade).

A direct consequence of expressing freedom was the narrative style. In Liszt’s opinion, the function of Music is not to traduce in sound abstract concepts, but to express what equivocates to the limited transposition of emotional states on the verbal level. This idea was named by Carl Dahlhaus ‘the topos of ineffable’, and he thought that ‘music is the access path towards truths that only ‘she’ can express and which can’t be expressed in ‘her’ deepest essence by verbal communication (even if it’s poetic).’[10] This is similar to the literary field, where writers had as basic condition the fight against the formal rhetoric aesthetics of Classicism in order to develop the romantic drama and other new genres. This aspect partially explains the decline of the classical sonata (as a genre) in the first decades of the 20th century, because of the interest showed by composers in innovative directions. Jean Pierre Bartoli explains the way that narrative style of the content influences the structure, generating a specific practice largely used during the Romantism – ‘aesthetics of fragment and sketch’, initiated by Schlegel[11], then used in literature by Hoffman and in music by Schumann (in his piano suites), Liszt (inAnnées de pélérinage). Therefore, Diderot stated that art needs ‘more life and less structure’. The most efficient technique to develop musical narrative style is to gather the musical figures in a single unitary work and represent a certain character or idea by means of a specific theme. The ‘fix idea’ used by Berlioz has been transformed by Liszt into a rhetoric principle of structural construction. It has been named the concept of ‘thematic transformation’[12], which allows the evolution of an entire work according to a certain narrative development. This technique has been approached firstly, in Vallée d’Obermann and Les cloches de Genève, and after that, Liszt would extend its usage in most of his works. Another narrative principle is the ‘continuous development’ present in Sonata in B minor, whose architecture is a synthesis of all techniques and principles of form introduced by classic composers: the principle of exposition in sonata and fugue forms (the recapitulation of the main theme in this work is a great fugato), the variation principle (which is used in order to create a series of metamorphosis and transformations of themes, by free variation), the strophic principle, based on juxtaposition, by inserting a strophic form inside the middle section of the sonata structure (section which is in contrast with the other moments, from the point of view of the tonal, agogic expression. I must point out again the fact that these principles are used freely and naturally, so as the lead to a cursive, fluent musical discourse.

Despite the open structures, Liszt has manifested the need for unity, and he has accomplished it in many ways. Another well-known concept in the romantic period, in all fields of art, is coincidentia oppositorum (the unity of contraries), which can be found, for example, in Faust Symphony; here, one can find specific musical themes ascribed to particular characters (such as Faust, Margarita, Mephisto). Margarita’s simple features are in deep contrast with Faust’s complicated personality. Mephisto, who is looking for the negative influence and the destruction of mankind, is musically represented by Faust’s theme and motives in a caricature-like manner. Margarita’s theme is the only one that remains untouched and victorious. Therefore, it can be said that another way of accomplishing the whole unity, the coherence of the entire work, is the technique of associating musical themes to different characters, situations, feelings, symbols, using them as circulating musical ideas (‘cyclic themes’) in all movements, leading to programme music.

From the ‘architectural’ point of view, Liszt has gone beyond the inherited structures, traditional forms and largely used patterns. He has always created his own structures, becoming a genuine inventor in this field.

The sound parameters are also treated as innovative elements, receiving from Liszt new appearances, influences and ‘colours’.

a) Melody – in Liszt’s way of creating, it has a magnetic attraction power, a certain impetus, enthusiasm and a deep restlessness specific to him. Melodic structures are based either on traditional items or on new, original elements.

• medieval modalism, in a Gregorian manner (in works such as Chapelle de Guillaume Tell, from the first book of Années de pèlerinage, or in Ballade no. 2 in B minor,Totentanz (Danse Macabre) and many others;

Example 2 – Franz Liszt – Totentanz, ms. 13-21, tuba à Theme Dies irae is exposed in the Dorian mode on D and harmonised using elliptical chords (without third)

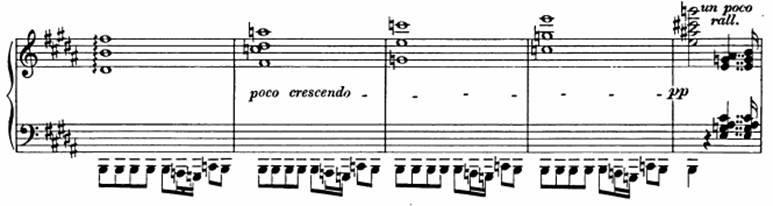

• pentatonic scale – in Au lac de Wallenstadt and Églogue from the first book of Années de pèlerinage;

Example 3 – Franz Liszt – Au lac de Wallenstadt, ms. 1-8

• the musical symbol of the cross – is the result of ascribing a religious semantic meaning to a pentatonic structure. This scale is based on five sounds – C, D, F, G, A.

Example 4 – Franz Liszt – Sonata in B minor, ms. 363-368 the pentatonic structure is transposed on D, E, G, A, B.

• the gypsy scale – used by Liszt in many works, in different melodic hypostasis and harmonic contexts.

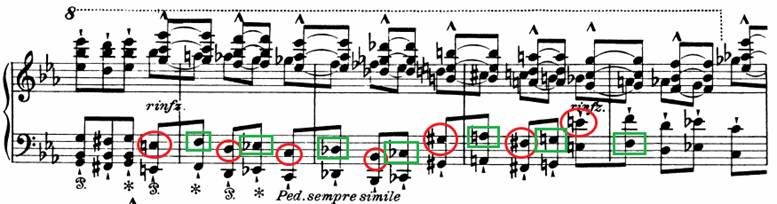

Example 5 – Hungarian Rhapsody nr.17, ms. 7-10

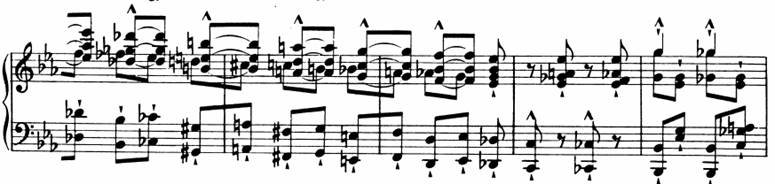

• the tone-scale – used by Liszt and other Russian composers before Debussy, who imposed it definitely in the European music as a new structure (the hexatone scale, consisting in six tones, without any specific gravitational centre), leading to attractive exotic sonorities.

Example 6 – Franz Liszt – The Great Chromatic Gallop, ms. 230-238

b) The rhythmic parameter is a result of Liszt’s interest in discovering and using folklore items, which enrich the musical discourse and offer its national sonority, original accents and a specific energy. Thus, rhapsodies acquire a very rhythmic personality, with Hungarian and gypsy influences.

c) Harmonic structures in Liszt’s works are based, similarly to melodic ones, on traditional elements, extending itself even more than the so-called ‘enlarged tonality’. There are chords composed of fourths, fifths, horizontal lines consisting in fourths, fifths, parallel un-functional sixths, chords mixtures, chords with Dominant function ninths, chromatic unsolved chords and so on. Examples are redundant in these cases, because Liszt work is abundant in this kind of exceptional situations, which are quite natural to him. In the same category of vertical structures can be included pedals and cadences.

The pedals used by Liszt can be organized in: fix pedals (like in the beginning of his Ballade no. 2), mobile pedals (simple or enriched with other notes), andaccompaniment-like pedals (which can be double or triple).

Example 7 – Franz Liszt – Sonata in B minor, ms. 727-735 – melodic pedal in the grave register, represented by an obsessive ostinato of the β motive.

Liszt’s cadences are perhaps the most spectacular when compared not only with his contemporaries, but also with the generations of composers from the following decades after his death. Focusing on the ending harmonic successions from his piano works, one can notice a great variety of chords chains, ajoutées elements, superposed structures which could hardly find harmonic explanations, unusual degrees to end musical phrases or even entire works.

For example, in the ending of the well-known work Vallée d’Obermann, Liszt inserted a confusing chain of chords: descending second degree, which is used as base for the major chord F-A-C, adding an augmented sixth (D sharp as an ajouté element, being the seventh chromatized degree of E minor). D sharp is preceded by a superior semitone, generating a very dissonant chord, searching its resolution in a descending line towards D sharp, then natural C, B, A and G sharp. The final solving chord of this chain has an unexpected auditory effect; the listener is not aware of the next dissonant element which would appear, the appoggiatura represented by C on the major chord E-G sharp-B (the resolution of C).

Example 8 – Franz Liszt – Vallée d’Obermann, final harmonic chords chain:

The beauty of these harmonic paradoxes does not have to be expressively searched in the way of chaining chords or in the very surprising modulations, because they emerge from the spontaneous and limitless phantasy of Liszt. He had directed the practise of modulation towards enlarged tonality, before Wagner did the same thing at a higher scale, reaching moments which could be characterised by future concepts like suspended harmony, multiple centres, sonorous scales without tonal-functional laws or Arnold Schönberg’s dodecaphonism. Thus, the Hungarian composer proved an unprecedented courage in constructing final harmonic formulas, but he never gave up to ‘gravitational centres’ imposed by tonal or modal systems. From this point of view, he proved to be a composer endowed with a special originality, avoiding the replacement of an automatism with other similar structures and trying to find in each case a proper, but personal solution.

d) Dynamics and agogic are fields having already been emancipated by previous Romantic composers. Franz Liszt did not make any particular improvements of these elements, but his way of conceiving the dynamic and agogic processes had a significant role in designing new structures. The main reason for highlighting this point is the free succession of intensities and tempos, which leads to strong contrasts, sometimes aggressive. Thus, he focused on creating musical colours and spatiality impression. ‘Aspects such as texture, sonorous intensity, violence and delicacy in gestures can replace the function of pitch and rhythm in musical organisation process.’[13]

4. Liszt – conductor and essayist

Beyond the two previously described sides (pianist and composer), Liszt has played a significant role in the history of music as a conductor. In 1842, he was given the title of Great Ducal Director of Weimar Court, where he used to come regularly until 1849, when he definitively settled down here, turning Schiller’s and Goethe’s town into a genuine centre of European musical culture. This is how Liszt began his conducting career. As an artist of the baton, he brought on stage many elements of his previous pianistic thinking and musical philosophy. Unlike the strictness of traditional conducting, the attitude promoted by Liszt was based on orchestral effects suggested by personal gestures, intensively expressed symphonic dramatic character, sonorous colour created by emphasizing certain melodic lines in the score or certain instruments (or groups of instruments). Neglecting the metrical accents, he was more interested in obtaining the sense of general, of unified wholeness, similarly to his younger contemporary, Richard Wagner. We can’t deduce any mutual influence between them or any inspiration source in their musical practice, but the history of music has focused on their co-operation, professional support and some friendly interaction between them. Liszt and Wagner had a series of common principles, the most important being the freedom of tempo, the elastic movement of musical discourse, in which every detail was adapted to musical, general needs.

Another hypostasis of Liszt is the writer, namely the musical critic. His literary work, written in French, has been organized in six volumes. Some texts were published during his life time in different magazines of the 19th century, such as Musical Journal, published in Paris. The most renowned work written by Liszt seems to be the monographic volume dedicated to Frederic Chopin, in which he proves a deep admiration for the Polish composer; here, he presents relevant details about his personality, about the genesis of certain works and relates different interesting events of their artistic life in aristocratic salons in Paris. Thus, his book achieves the quality of a historical document of a high value. Liszt was aware of the importance of the entire Romantic phenomenon, implying artists from different fields, leading to great works of the 19thcentury. Even if Chopin was the opposite of his artistic style, they were both major figures among the entire constellation of Romantic artists.

Other literary works signed by Franz Liszt are: About artists’ situation and their place in society, The letter of a wanderer towards George Sand, The letters of a bachelor in music, Paganini (obituary notice). The amplitude and certain stylistic subtleties of Liszt’s literary work generated many discussions concerning the authentic signature of the Hungarian composer from his writings. The most important equivocal source is the chronologic structure of his writings, divided in two categories: the first between 1835 and 1841, and the second between 1849 and 1859. The two periods coincide with two important relationships, in their climax, with a significant influence on Liszt’s existence. In 1841, his connection with countess Marie d’Agoult gets more and more deteriorated, and that year is also significant when speaking about ceasing his essays to musical critics. The second series of articles belongs to the period of cohabitation with Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, which is not just a simple coincidence. The relation between Liszt’s literary publications and the two famous women who had won his interest and appreciation is obvious, but one can’t establish exactly how much they contributed to his writings. The most part of information has been provided by Liszt’s correspondence with the countess, the princess and other close friends. There are musicologists who had access to those letters, thus revealing intimate details of the writing process while being connected with the two ladies. Emil Haraszti, Peter Raabe, Alan Walker have written about these aspects in their monographic works. Lina Ramann is known to be the first author of a complete biography of Franz Liszt, written under the attentive supervision of Princess Wittgenstein. Based on the sketches found among his manuscripts, it has been concluded that Liszt wrote entirely some of his essays, while other had a writing process which involved the inspiration or contribution of the two women. Researchers think that Liszt used to write down his ideas, to organize and reinforce them, leaving the developing process, the literary polishing and final artistic ‘touch’ to countess d’Agoult and later to Princess Wittgenstein, who were endowed with a literary gift. Musicologist Serge Gut has concluded that ‘Liszt’s co-operation with Marie d’Agoult proved to be useful and positive, because her help was graceful, well balanced and intelligent; his collaboration with Carolyne de Sayn-Wittgenstein was rather misfortunate, due to a certain overflowing verbal exuberance, that led to invasive stylistic print. His works from the first period are naturally written, pleasant to read and coherent from the stylistic point of view; those from the second period are quite awkward, bombastic and hard to read, but they can offer precious information if they are read carefully, with the necessary patience.’[14]

Beyond these details about writing, one has to mention the most significant literary and critical work accomplished by Liszt: Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie (About gypsies and their music in Hungary). Finished in 1859, this work shows some special research qualities in a field which hadn’t been theorized yet at that time. His way of expressing ideas and arguing them in a complex research work has some Romantic features, such as declamation, metaphorical phrases and excessive enthusiasm, which were probably effects of the same outside intrusion in his individual activity. Despite these things, the lack of unaffectedness and naturalness does not affect the quality of the content. Maybe Liszt hasn’t had a clearly established method to gather information and to organize his ideas, which weren’t always very well sustained, but his work is placed among the most important documents in the history of Hungarian folkloric research field.

5. Conclusions

With his multiple artistic personality touched by the glowing spark of the genius, Franz Liszt has worked on many levels, dedicating his life to those fields which made their call from an early age: piano playing, composition, conducting, also being interested in writing about his time and contemporaries. He tried to compose one single opera (Don Sacho, or The Castle of Love), but he focused his artistic energy towards those musical genres where his gifts were consciously turned into great musical masterpieces. Speaking from the perspective of temporal evolution, one can make a difference between Liszt the young artist – virtuoso, extremely energetic pianist, who was able to compose and play Chromatic Gallop, Transcendental Études, countless transcriptions, paraphrases and reductions of great symphonic works for piano, turning his instrument into a real orchestra, and Liszt the older man, a brilliant symphonist, a true ‘inventor’ in music (author of symphonic poem, recital, innovative free structures), promoter of classical programmatic genres (symphony, sonata), creator of depictive ‘musical paintings’, but also author of religious genres (masses, oratorios, chorales). In his late years, virtuosity is not a purpose any longer; it merely became a mean to express the poetical meditation and intimate spiritual beliefs.

As for his impact on the 20th century’s musicians and on those from nowadays, one can make an interesting inversion of Liszt’s ages. His hypostasis as a mature artist could be perceived as a face of his refreshing youth, characterised by deeply vibrating feelings and thoughts, rich inspiration, great delight of living and enjoying all his experiences, despite the years that added to his existence.

In the end, we find it proper to remember his famous funny action, ‘committed’ by Liszt in one of his European tours, when he had to fill in the accommodation paper of a hotel from Geneva. Common questions were answered unusually, with a great sense of humour:

Occupation: Philosophic Musician

Born in: Parnas

Coming from: Doubt

Travelling to: Truth

Bibliography

BARTOLI, Jean-Pierre, article/ chapter ‘Rhétorique et narativité musicales au XIXe siècle’, en Musiques : une encyclopédie pour le XXIe siècle. 4th vol.: Histoires des musiques européennes, under the direction of Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Paris, 2006, page 1026.

GUT, Serge, Franz Liszt – les éléments du langage musical, avec un préface de Jacques Chailley, Ed. Armoniz ZurfluH, Paris, 2008.

LISZT, Franz, Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie, apud. Serge Gut.

ROSEN, Charles, La génération romantique (Chopin, Schumann, Liszt et leurs contemporains), Gallimard Editions, 2002.

SAVA, Iosif, Bucuriile muzicii (The joys of Music), Musical Publishing House, Bucharest, 1985.

SCHONBERG, Harold, Vieţile marilor compozitori (Lives of the Great Composers), Lider Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008.

SPERANŢIA, Eugeniu, Medalioane muzicale (Musical Medalions), Musical Publishing House of the Composers Union from Romania, Bucharest 1966.

ŞTEFĂNESCU, Ioana, O istorie a muzicii universale (A History of the Universal Music), The Publishing House of the Cultural Romanian Foundation, Bucharest, 1998.

SANDU-DEDIU, Valentiana, Choices, attitudes, affects. About style and rethoric elements in music, Didactic and Pedagogical Publishing House, Bucharest 2010.

[1] Phrases quotated from Harold Schonberg, The Lives of the Great Composers, Lider Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008, pages 189-201.

[2] Eugeniu Speranţia, Musical Medalions, Musical Publishing House of the Composers Union from Romania, Bucharest 1966, page 81.

[3] Ioana Ştefănescu, A History of the Universal Music, The Publishing House of the Cultural Romanian Foundation, Bucharest, 1998, page 340.

[4] Iosif Sava, The joys of Music, Musical Publishing House, Bucharest, 1985, pages 380-381.

[5] Serge Gut, Franz Liszt – les éléments du langage musical, avec un préface de Jacques Chailley, Ed. Armoniz ZurfluH, Paris, 2008, page 1.

[6] Serge Gut, op.cit., page 266.

[7] Franz Liszt, Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie, apud. Serge Gut, op. cit., page 266.

[8] Valentina Sandu-Dediu, Choices, attitudes, affects. About style and rethoric elements in music, Didactic and Pedagogical Publishing House, Bucharest 2010, pages 145-146.

[9] Liszt, quoted by Harold Schonberg in Lives of the great composers, Lider Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008, pages 192-193.

[10] Jean-Pierre Bartoli, article/ chapter ‘Rhétorique et narativité musicales au XIXe siècle’, en Musiques: une encyclopédie pour le XXIe siècle. 4th vol.: Histoires des musiques européennes, under the direction of Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Paris, 2006, page 1026.

[11] In Charles Rosen’s volume, La génération romantique (Chopin, Schumann, Liszt et leurs contemporains), Gallimard Editions, 2002, page 81, one can find quoted the definition given by Friedrich Schlegel to the notion of ‚fragment’ in the 19th century: ‘Similarly to an artistic work in miniature, a fragment has to be completely detached by the surrounding world and sufficient to itself, like a hedgehog.’ The hedgehog, as Charles Rosen continues, ‘is an agreeable creature, which rolls like a snowball when feeling in danger. His shape is well-defined, but his outlines and edges are vague. The metaphor of the hedgehog is spherical, built after a perfectly geometrical pattern, and this is why it is adequate to symbolise the romantic way of thinking, beginning with the attractive image of a body which is protecting himself on the outside using his own body features. Similarly, the fragment is broken from the outside context. In fact, its isolation is aggressive: it gets detached from the world as much as the hedgehog feels protected.’ (page 82)

[12] Jean-Pierre Bartoli, article/ chapter ‘Rhétorique et narativité musicales au XIXe siècle’, en Musiques : une encyclopédie pour le XXIe siècle. 4th vol.: Histoires des musiques européennes, under the heading of Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Paris, 2006, page 1034.

[13] Valentina Sandu-Dediu, op.cit., page 146.

[14] Serge Gut, op.cit., page 24.