TYPES OF SETS OF ARCHITECTURAL GRAPHICS AND TEXTS IN BULGARIAN PUBLIC SPACE – XX CENTURY

Bulgarian Academy of Science, Sofia, Bulgaria

stelabt@gmail.com

Abstract

The study is part of a bigger research project called “Bulgarian architectural graphics of XX century – problems and tendencies”. The aim of this paper is to explore combinations of architectural graphics and verbal descriptions from XX century. The chosen case studies are spread and made public in Bulgaria by professional magazines, articles or other scientific issues. Hence in the article are analyzed main features, forms and applications of graphics and texts and their links and mutual references in the final composite architectural message. The degree of information coherence of verbal and visual parts, used with various purposes, like education, propaganda, marketing, etc. is examined in three directions: as fully and partially connected, and as parallel messages. The study investigates the semantic relations between texts and graphics based on their contrast, lines of consequence or ways of harmonization and integration.

The expected results are in the areas of history of architecture and architectural graphics.

Introduction

Commonly accepted, architectural graphics is a tool of creating, developing and/or communicating architectural concepts and projects. Although their “iconic” or “comic strip” essence architectural graphic signs as any technical form of communication require basic education in the area. Tables, various schemes and graphs are common tools when writing about architecture, same as the constant dispersive mixture of iconic and symbolic (verbal and numeric) signs.

In the paper, the term “architectural graphics” will be used with the meaning of unique written language and a main factor in the design processes. As it is used to describe complex three-dimensional items, architectural graphics elements may include not only two-dimensional plans, perspectives, schemes, sketches, drawings, CAD files, photos or other images, but also attached and embedded one-dimensional texts and descriptions, typological references comparisons and claims, various forms of graphs, tables, and, of course, new media – real models, video or interactive data sets and etc. Each of those data carriers can exist independently as channel and media, or be grouped with others aiming the transfer of information about one and the same project.

This article is focused on the most common cases of semantic flows and combinations created with the verbal, one-dimensional texts, and the visual two-dimensional images. Architectural scientific notes and articles are seen as systems of higher order – as sets that are combining parallel flows of verbal analyzing substances and some or all other visual elements of architectural graphics.

The semantic capacity of texts and images can vary accordingly to their main subject and message. Usually verbal texts are used more for analytical and theoretical, and therefore implicit, semantic needs: they specify principles, methods and typologies; they compare different objects and stress on chosen features, elements and factors. Although it is possible to use some protocol for verbal information structuring, like series of coordinates, varying matrixes, and selected dimension data to create an explicit verbal description of a building. (For example, some procedures of explicit verbal transcript are in fact what computers are programmed to do, to create an architectural Building Information Model.)

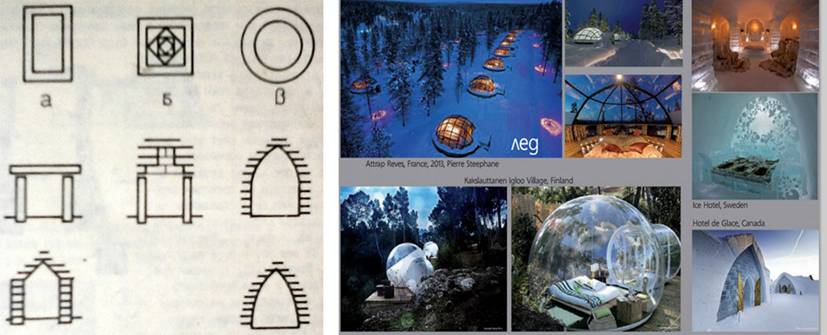

One of the founders of Morphosis, Thom Mayne, quoted by Forty (2000: 37) says “Drawings and Models […] allow a degree of precision often elusive in verbal discourse”. Images and especially drawings are commonly expected to be more explicit and accurate, describing very particular buildings, dimensions, materials, proportions, geometrical connections, etc. Still, a simplified image can be used to mark a typology (as in the example on fig. 1-left, where Русева Ruseva (1981-1982: 312) is explaining the various structure schemes of a Thracian tomb cupola). This image refers to no explicit, actually existing tombs, and still it argues on possible structure issues of a great number of antique buildings. Another example of implicit data transferred through images can be seen on Fig.1-right, where Давчева Davcheva (2014: 26) gives examples on accessing and exploring the presence of ice in alternative hotel forms. As an opposition of the simplified structure models, in Давчева Davcheva image are used very concrete, existing objects, which are colligated in a concept, due to one material use and repetitiveness.

Figure 1: Left: Thracian cupola typology; Right: Use and sense of ice in hotels structures

Now it is possible to conclude that images and verbal descriptions in architectural graphic language are used in equal parts for data transfer, depending on an author’s choice of explanation methodology. A sender of graphic architectural messages may choose either the only one communication channel (like full set of drawings and images or systematic complete verbal descriptions) or a mixture of them both. Then sometimes as both verbal and visual data flow are used in parallel to deliver one and the same object, the receiver of the data could accept them even as duplication of the data flow – for example when images are explained in detail through the verbal texts.

In fact, it is hard to determine the minimum verbal and visual parts that are needed in order to transfer properly the needed architectural information. A possible reason is the very nature of verbal and visual descriptions. As first, each of them is suitable to stress efficiently on specific building elements and characteristics – just naming the structure types, or showing a line of silhouettes. As second, both verbal (one-dimensional) and visual parts (two-dimensional) of a message are meant to express a three-dimensional architectural structure, therefore their combination somehow increases receiver’s ability to decode this structure. And as third, one may notice the various cognitive setting of architects, authors or scientists, which is a reason for quite contradict opinions on the role of a drawing in the design process. There are the well-known words of Carlo Scarpa quoted by Murphy (1990: 12) “I want to see things, I don’t trust anything else. I place things in front of me on the paper so that I can see them. I want to see therefore I draw. I can see an image only if I draw it.”, but also the statement of Frank Lloyd Wright “I no longer touch pencil to paper until the idea of the design is so fixed within my own imagination that I am arranging the furniture and placing bowls of flowers in the building. Then I go to paper and put it down.” quoted by Futagawa (1985: viii). In a bit different context, but in still valid circumstances, the researcher of antique Thracian tombs, Русева Ruseva (2013:17) explains the processes of creating architectural objects in the Antiquity like “The words are in the beginning of any creative process. Thoughts, shaped as ideas, which are seeking the rendering of spiritual categories into material objects, are the reason of occurrence, development and existence of architecture”.

Method

In the article I shall focus on two cases of combining verbal and visual flows of architectural data: the full coherence, where verbal and visual parts show complementing data aspects of the same architectural object; and the parallel flows of images and verbal parts, where visuals are not directly connected to the project mentioned in the text.

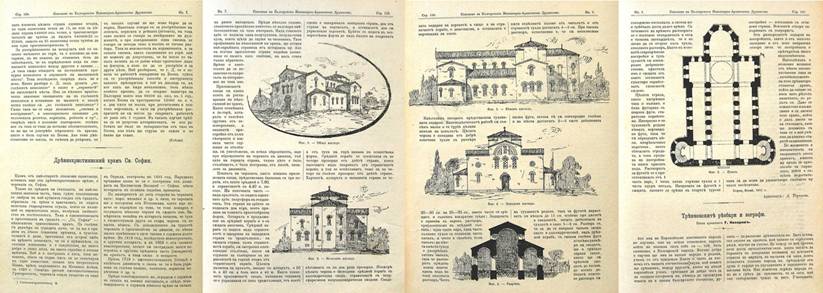

The first one is the most common case concerning the verbal and visual flows in an article. This often is the most convenient way to present a project in magazine or online. A good example of that is the representation of the ancient Christian church “St. Sofia”, published in the magazine of the Bulgarian architect-engineering chamber, byТорньов Tornyov (1901), shown on fig.2. In the article, the rich images are creating a strong visual impression of the existing building, and the verbal parts are adding data like details, numbers, quantities, myths, stories or even wishes. In other articles verbal explanations are also used as a rhetoric tool to cover opinions and comments, building commission and design stories and typological or real object comparisons. Combinations of drawings (including various building outlooks and their space organizations like plans and sections) and descriptions of the project circumstances and numerical data (sometimes used to defend or attack the chosen paths and concepts) continue in almost all XX century publications as a certain set, a stable data structure.

Figure 2. Article for the ancient Christian church “St. Sofia”.

The parallel flows of verbal and visual data in an article are not that widespread, but still are applied in diverse situations. As borderline examples about this, could be accepted the absence either of verbal texts, or images in one architectural representation. Until the technology for multiplying images and drawings was developed, the buildings were presented in public texts verbally, which was accepted as methodology. But in XX century, the technology was well-know, and both of verbal and visual elements were used, even though multiplying of images, drawings and photos was considered a bit expensive. Therefore the lack of one of the communication channels should be accepted as personal or editorial choice. In fact from the beginning of XX century this choice was somehow loaded with additional meaning. For example use only of images and no comments was widespread as a way to cover competition results for more ordinary buildings almost until the end of century. Verbal and only verbal elements were usually applied in stylistic and philosophic discussions, attack or defense of a chosen life, urban or competition concept, or analysis of project circumstances.

In both mentioned above cases, the use of single channel communication suggests the impersonal and unbiased author or editorial position. Somehow, the use only of verbal explanation is also assumed as more classical and with higher theoretical value. With no images are lots of researches like those conducted or edited by ДжангозовDjangozov (1943), Обретенов и Стамов Obretenov and Stamov (1972), Христова Hristova (1979) etc. Modified versions of this “highly theoretical” point of view are also some architectural books or studies illustrated in artistic or conceptual manner like the work of Класанов Klasanov (1992) about the technicism tendencies in architecture.

There were also cases of using single channel communication for the expected existence of reasons to underrate a theme or project – a neglected author, highly questioned project etc.

In the end of the century when the world embraces the new technology and the Internet, it is common to use only images for another, third reason – their attractiveness, the haste of their perceiving and their fully accessible “language”. Verbal explanations were accepted by the public as too tiresome and unnecessary. Even now the common representations of any architectural object in the Internet are several realistic or photographic views and the object name.

In Bulgarian public space during XX century were also some interesting tries of embedding images and text in contradict or independent way. In the article I shall examine two specific case-studies: forms of implied messages and the addition of hidden meanings.

The implied messages were constructed when the author was expecting knowledge levels and shaped opinions from his public, or believed truly in the images solidity. A good example of this is the article of Ненов Nenov (1915) who was disturbed by some inappropriate tendencies in the Bulgarian architectural competitions. Nenov tracks various executed competition procedures and results and complains about the practice of transferring the winning entry to a non-winning but cheaper competitor, and creating unhealthy atmosphere in the guild. His article is illustrated with project drawings by architect Lazarov, who, as it is mentioned in the text, had won the second prize in a competition but no first prize was ever given. Although the detailed analysis of past competitions, one of the implied message of this article, conducted by the images is about the high quality of Lazarov’s designs, and the injustice done towards him as a competitor.

Another form of implied messages can be seen in two retrospective articles in Serdika magazine – an issue published by Sofia municipality in the period 1937-1952. The first chosen articles by Михайлов Mihaylov (1939) is following the deeds of Sofia municipality for a five year period. The article is 39 pages long, divided in multiple sections about the new administrative and financial structure, the building activities, road and transportation news, water, and electricity deliverance, sewage structure, gardens and parks, hospitals and other health institutions and arrangements, school and social support. All of the sections are illustrated with sustained images – the new municipality crew, the built edifices and structures, sometimes with plans and details, and their happy users. The architectural part contains even a first try of photo realistic montage of a project and pictures of various gypsum house models. The implied messages of these images are of course the happiness to live and work in Sofia, same as the big difference that is made for the observed 5 years. Some 8 years later, under the name “69 years from Sofia liberation” the magazine published 7 page article divided on financial, social, building, health, culture and etc. sections but all the accompanying images were an artistic sketch and some committee members. The article bird-eye view is shown on Figure 3. The shift of the used image themes is outstanding, although of course those years are one of the most dynamic periods of the XX century. It is really amazing, how architecture, which is always supposed to be material three-dimensional object, holder of aims, functions and space, is not depicted anywhere, although it is mentioned in the article. Somehow anything material and solid is taken away from the city as an institution or habituating structure, and also from its management. Instead of any architecture, or citizens, in 1947 the presented committee people are materializing the concept of “soviets” and the new reign, and they are to become the new face of Sofia. The implied message of these images is also about the watching and evaluating governing power, because of the chosen way of presentation of the authority member – sitting on large conference tables, backed by portraits of communist heroes.

Figure 3. Article in Serdica magazine, 1947.

Although the message of the pictures in Serdika magazine is not so direct, it is visible to all of its targets – who are people living and consuming the city. This kind of implied propaganda information is extremely popular in public presentations during the second half of the century. After the fall of the communist regime, the major politics are often replaced by popular culture personalities, same as their heroic inspiration is traded off to marketing ideas.

Hidden messages on the other hand are not so openly transferred as the implied propaganda epistles. They may or may not be visible; they may or may not reach some receivers. A well-known example of misjudged hidden message in Bulgarian public space is a forbidden and burned epigram book by Radoi Ralin (1968), illustrated by Boris Dimovski. On one of the book illustration, under the epigram “Blue paunch, deaf for knowledge” is drawn a pig, which tail is accepted by the censorship as an imitation of Todor Zhivkov’s (the communist head of state in the period) signature.

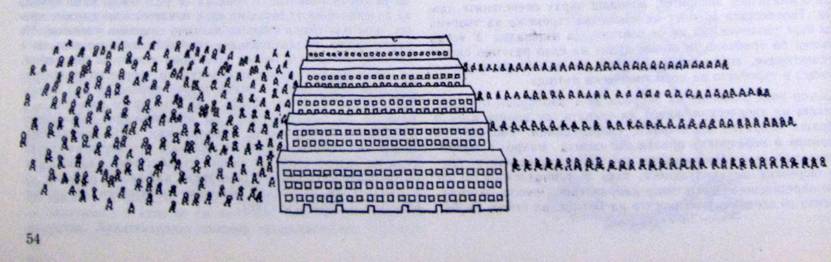

Examples of possible hidden messages in architectural themes are some of the pictures in the study of Кръстев Krastev (1979). The research is focused on the processes, needs, developments and expectations of all involved in an architectural design process. The book is illustrated by its author with witty and sometimes satirical schemes and images analyzing the phases, intentions and perceptions of different architectural objects. Some of them literally so close to the broadly accepted at the period ideas, that when drawn on paper they are touching the limits of the absurd. An image by Krastev analyzing the use of the block buildings in huge new socialist city districts is shown on Figure 4.

Figure 4. Illustration by Krastev (1979: 54)

In Krastev’s picture, blocks are shown as a space distributor, which are assorting the chaotic crowd movement. But looking at it, it is possibly also to notice the loss of human identity and the emergence of sense of uniformity and obedience created in the block public space. The image is not criticizing, or arguing, but is making some concepts truly visible and clear.

Results

There are a great amount of published architectural or scientific texts in Bulgarian public space, and until now, they were never been an object of research from graphic and semiotic point of view. As any illustrated articles, architectural studies usually combine visual and verbal parts. Still their aim is a bit different from the other texts, as they are expected to reveal objectively true portrait of the analyzed buildings.

During XX century, images are mostly used to support and illustrate the verbal parts of studies. They are accepted as parallel data flow, following and imitating the verbal analysis. However a various borderline cases existed, including single-channel communication or the deliverance of additional, implied or even hidden messages to their readers. The perception of those messages depends deeply on the context and the environment of a reader and on his knowledge and state of being.

Hidden messages become extremely popular in the period of the socialist governing the state of Bulgaria, and therefore are applied in even more formal, technical languages like the one of architectural graphics. But in fact variations of channels and methods of communication are enriching the processes of data transferring and the architectural language vocabulary and semantic capacity.

Reference List

FORTY, Adrian. 2000. Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson.

FUTAGAWA, Yukio. 1985. Frank Lloyd Wright: Preliminary Studies; 1889-1916. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita.

MURPHY, Richard. 1990. Carlo Scarpa and Castelvecchio. London: Butterworth Architecture.

ДАВЧЕВА, Мария. 2014. Метаморфози на съвременните хотели. Архитектура (2). 26-31. DAVCHEVA, Maria. 2014. Metamorfozi na savremennite hoteli ‘Contemporary hotel metamorphosis’. In Architecture (2). 26-31.

ДЖАНГОЗОВ, Константин А. 1943. Българска национална архитектура, АБВ, София. DJANGOZOV, Konstantin A. 1943. Balgarska natsionalna arhitektura ‘Bulgarian nacional architecture’ ABV, Sofia.

КЛАСАНОВ, Методи. 1994. Техницизмът в архитектурата, БАН, София. KLASANOV, Metodi. 1994. Tehnitsizmyt v arhitekturata ‘The technicism in architecture’, BAS, Sofia.

КРЪСТЕВ, Тодор. 1979. Архитектурно творчество, Техника, София. KRASTEV, Todor. 1979. Architectural creation, Tehnika. Sofia.

МИХАЙЛОВ, Р. 1939. Пет години Нова Столична община. Сердика, Столичната община (5) 3–34. MIHAYLOV, R. 1939 Pet godini nova stolichna obshtina ‘Five years new capital municipality’. Serdika, In Capital municipality (5) 3–34.

НЕНОВ, Георги П. 1915. Архитектурните ни конкурси и съдбата на нашите архитекти-конкуренти. Списание на БИАД в София. (22) 172–176. NENOV, George P. 1915. Arhitekturnite konkursi i sadbata na nashite arhitekti-konkurenti ‘Architectural competitions and the fate of our architectural rivals’ In Magazine of Bulgarian architect-engineering chamber (22) 172–176.

ОБРЕТЕНОВ, Александър & С. СТАМОВ (ред.). 1972. Комунистическата идейност и архитектурата, Техника, София. OBRETENOV, A. & S. STAMOV (ed.) 1972 Komunisticheskata idejnnost v arhitekturata ‘Communist concepts in architecture’. Tehnika, Sofia.

РАЛИН, Радой & Борис ДИМОВСКИ. 1968. Люти чушки, Български художник, София. RALIN, Radoy and Boris DIMOVSKY. 1968. Ljuti chushki ‘Chilies’, Bulgarian artist, Sofia.

РУСЕВА, Малвина. 1981-1982. Тракийската гробищна архитектура. Годишник на ВИАС (1-1) 305-313. RUSEVA, Malvina.1981-1982. Trakiyska grobishtna arhitektura, ‘Thracian tomb architecture’. In UACEG Yearbook (1-1) 305-313.

РУСЕВА, Малвина. 2013. Методика за научно изследване на тракийската архитектура. ИИИзк – БАН, София. RUSEVA, Malvina. 2013. Metodika na nauchnoto izsledvane na trakiyskata arhitektura ‘Methodology of research over the Thracian architecture’. Institute of Art Studies, BAS

СЕРДИКА. 1947. 69 години от Освобождението на София, Сердика (1) 5-11. Serdika.1947. 69 godini ot osvobojdenieto na Sofia ‘69 years from Sofia liberation’. InSerdika (1-2) 5-11. Digital archive of the magazine is available at Sofia library website accessed on 31.01.2015.

ТОРНЬОВ, Антон. 1901. Древнехристианский храм „Св. София“. Списание на Българското инженерно-архитектно дружество. (7) 128-131. TORNYOV Anton. 1901. Ancient Christian church “St. Sofia”, In Magazine of Bulgarian architect-engineering chamber (7) 128-131.

ХРИСТОВА, Елена. А. 1979. Естетика на архитектурата, Техника, София. HRISTOVA, Elena A. 1979. Estetika na arhitekturata ‘Architectural aesthetics’. Tehnika, Sofia.