THE ROLE OF SOUND IN FILMIC EXPERIENCE: A COGNITIVE SEMIOTICS APPROACH

Jorge Tadeo Lozano University, Bogotá, Colombia

juan.conde@utadeo.edu.co

Abstract

In the Semiology of Cinema tradition sound was assumed as a particular type of “expression substance” among others, an ingredient of “syncretic” semiotics. From this perspective, films are closed texts made of codes decipherable by the spectator (Metz, 1971, 1974), one of which would be the sound code. After the cognitive turn in film theories (Bordwell, 1987; Branigan, 1992; Currie, 1995; Bordwell & Carroll, 1996; Grodal, 1999, 2009, among others), film (and audiovisual) semiotics is interested in accounting for the viewer’s experience. This experience is now understood under the same parameters of real life experience, to the extent that humans use the same skills to understand movies that to deal with reality. Some researchers have devoted part of their theories to the description of sound and hearing experience in cinema from different approaches: ecological (Anderson, 1998; Anderson, Fischer, Bordwell et al, 2007), socio-historical (Altman et al, 1980, 1992, 2001, 2007) “eclectic” (Chion, 1985, 1991, 1998, 2003) or even cognitive – in a broad sense (Jullier, 1995, 2002, 2012). Nevertheless, the bridge between cognitive theories and film semiotics is still weak, particularly when dealing with the multimodal dimensions of spectatorship experience.

To address the role of sound in filmic experience with more powerful tools, in this presentation I propose to follow the current trend of cognitive semiotics and its link with phenomenology and cognitive sciences (Sonesson, 2009). First, I will show the insights of philosophy and phenomenology of sound (Ihde, 2007; O’Callaghan, 2007; Nudds, O’Callaghan et al., 2009): the phenomenological description of the auditory field and sound horizons, and the idea of conceiving sounds as events in hearing experience. Second, I will present some discoveries of cognitive research from an enactive perspective, about the intersubjective exploration of sound spaces (Krueger, 2006, 2000, 200). Third, I will link these ideas with a general description of event perception and conception (Zacks, 2008, 2010: Zacks & et al., 2011), particularly in film comprehension (Zacks, Speer, and Reynolds, 2009; Zacks & Magliano, 2009). Finally, I will integrate all these insights in the context of a new semiotic theory: agentive semiotics (Niño, 2013a, 2013b; Niño, 2014, forthcoming). This theory provides precise criteria to distinguish (but also integrate) the experience of "semiotic scenes" (intentional constructions assumed here as a particular type of events) and the experience of the world. Thus I hope to provide a new approach to understand the role of sound in the (multimodal) experience of film spectatorship.

1. Introduction: three paradigms in film (sound) theory

In the tradition of film theory, sound was assumed with different levels of attention across history. We can use Francesco Casetti’s scheme about the stages of film theory (Casetti, 1999: 7 – 20), to place the multiple authors that have shown interest in the sound track in a broad sense (that is, not just music but all the material expressivity of sound, including sound effects, words, ambient sound, etc.).

According to Casetti, there are three periods, each one with its own objectives, approaches and criteria to build knowledge about cinema. In each of the three, there are theorists who have addressed the role of sound in film experience. In the first period, I want to locate Siegfried Kracauer (1997 [1960]: 102 – 131), because he was the one who proposed the most systematic list of criteria to talk about the relations between sound and the other components of narrative cinema.

1.1. Kracauer’s proposal

In Kracauer’s terms there are six axes of relations between sound and image. According to Roger Odin (1992) the axes two, four and five are the most important, given that almost all sound theorists after him have used these three criteria, in more or less the same words. Thus, theorists like Percheron (1973), Gardies (1980), Château & Jost (1979) and even Odin himself (1992) have focused in this kind of relationships, using different models and schemes.

1.2. The semiology of cinema and the material expression of sound

This brings us to the second moment, the one in which, according to Casetti, film semiology was born. The main character in this period is, of course, Christian Metz, the father of this discipline, for whom sound is just a particular type of “expression substance” among others, an ingredient of what greimasians will call later a “syncretic” semiotics.

From Metz’s perspective, films are closed texts made of codes decipherable by the spectator (Metz, 1971, 1974), one of which would be the sound code. Later, the so-colled “second Metz” put his emphasis on describing how films are understood. In that sense, he opened the gate to a new kind of approach. Nevertheless, he continued to talk about the relationships between systems and codes, manifested in a closed object: filmic text.

1.3. Film narratology and enunciation theory

In the transition between the second and the third paradigm, film narratology was developed. The main authors of this approach returned to distinctions similar to those proposed by Kracauer. Also, in this period theories of (audio) visual enunciation were developed, and the spectator, named the “enunciatee”, timidly appeared.

Here, movies are complex narrative constructions that “cognitively” and “perceptively” place viewers facing the information of the story world. The concepts of auricularisation and ocularisation, proposed by Francois Jost (and debelopped also with André Graudreault) came to the field to explain the different ways in which spectator is acoustically and visually positioning in the narration (see Jost, 1987, 1992; Jost & Gaudreault, 2000).

In a way, theories of audiovisual enunciation are placed between the second and the third paradigm, since these theories focus on immanent film “forms”, but also on spectator’s activity. In fact, the third paradigm called by Casetti the Theories of field, represents the “pragmatic turn” in film theories. With respect to sound, two interesting approaches arouse: Michel Chion works on sound, music and voices in cinema, and the so-called “cognitive turn” given by David Bordwell, Nöel Carroll, and others. In this point, some theorist who came from the old traditions, started to approach cinema in a new way.

For instance, Roger Odin, who developed the semio-pragmatic theory, intended to understand cinema from the spectator’s side. According to Odin, it is necessary to describe the inferences that spectator needs to do in order to understand sound-image relationships. Now, Odin talks about film hearing (l’écoute filmique), Spectator’s motivations (selective hearing) and attention (Odin, 1990: 238 – 239).

Odin and other authors of this period of transition continued to describe the same film features before called as “material expressions”, but now, at least, they pointed them as cues to spectatorship activity. See, for example, Odin scheme on the codes of construction of sonic sources (Odin, 1990: 251 – 254), or Michel Chion’s famous scheme of the three zones of filmic sounds (Chion, 1994: 73 – 80). Both schemes emphasizes on the way in which spectator perceives or infers the sources and the features of sounds with the point of reference of the filmic screen.

In the same way, French theorist Laurent Jullier, who proclaims his approach as “cognitive”, extends the levels of hearing experience to different “worlds” that the viewer face when watching narrative movies: the narrative world, the hetero-universes (subjective, possible worlds), the “pit” world, and the making and projection (or broadcast) worlds. And that's how we arrive to the most interesting point of this story. Because when theorists start to talk about the actual space of sounds, or the “pit”, or even the “speakers” in the theater, or in the TV set, is increasingly difficult to continue with the idea of a film “text”.

Nevertheless, the first cognitive film theories seem not to pay particular attention to the sound. In fact, David Bordwell, the one that initiated this movement, he himself rests more in the “formalism” that in cognitivism in his description of the different aspects of cinema. In his work with Christin Thompson, Bordwell describes filmic sounds in very similar terms to the Kracauer tradition: Rhythm, Fidelity (to the source) space (related to the Diegetic/nondiegetic distinction), resources of diegetic sound, and time (in terms of synchronism/simultaneity).

However, Bordwell and Thompson also mentioned the perceptual properties of sound (loudness, pitch, timbre), and the operations that film makers execute over sound materiality: selection (choosing), operation (manipulating), and combination (mixing). And most important: when talking about space, Bordwell and Thompson include the idea of “Sound perspective”, related to the actual spatial (nor diegetical) properties of sound (volume, stereo, surround sound).

1.4. The cognitive turn

Among the main authors that developed cognitive film theory, just few devote a particular section to sound issues: particularly, there is a section on the famous bookPost-theory (Bordwell and Carroll, 1996) dedicated to music in cinema, with articles by Jeff Smith (pp. 230 – 247) and Jerrold Levinson (pp. 248 – 2832). And with a broader approach to sound, Joseph Anderson and his seminal work based on Gibson’s ecological perspective Anderson, 1998), devotes some pages to the description of the auditory system (chapter two: pp. 26 - 28) and to the relations between sound and image (chapter five: pp. 80 - 89). In the same spirit, Anderson and Bordwell edited a book in which appears two articles on acoustic events (the first one, Background Tracks in Recent Cinema by Charles Eidsvik; the second, Acoustic Specification of Object Properties, by Claudia Carello, Jeffrey B. Wagman, and Michael T. Turvey).

Thus, the cognitive film theory has opened a completely new approach to the role of sound and image in filmic experience. And this is how we arrive to the subject I want to propose: if film semiology and film narratology (both more or less based on structuralism) impose the text metaphor in the field of film theories, cognitive approaches invite us to take a new formula: we are going to start talking about film experiences, based on film events.

As a point of departure, I want to refer another theorist who has also defined cinema as event, with an emphasis on sound, Rick Altman. In his own words:

Considered as a text, each film appears as a self-contained, centered structure, with all related concerns revolving around the text like so many planets. In opposition to the notion of film as text, I have found it helpful to conceive of cinema as event. Viewed as a macro-event, cinema is still seen as centered on the individual film, but according to a new type of geometry. Floating in a gravity-free world like doughnut-shaped spaceships, cinema events offer no clean-cut or stable separation between inside and outside or top and bottom (Altman, 1992: 3).

In his model Altman integrates the worlds of production and reception, and he identifies twelve attributes of cinema that had been hidden because of the “textual approach to cinema” (Altman, 1992: 4 – 14). The general idea of all these attributes is that cinema is a live embodied experience: watching a movie implies been in a concrete space (the theater, our homes, a train, etc.), facing diverse kind of reproduction technologies, in a specific projection (or broadcast) in a particular circumstance. For example, the textual approach to cinema makes us emphasize the bidimensionality of the image:

Though conventional speaker placement attempts to identify sound sources with the two-dimensional area of the screen, sound occurs only in the three-dimensional volume of the theater at large. Because sound is always recorded in a particular three-dimensional space, and played back in another, we are able to sense the spatial cues that give film sound its personalized spatial signature (Altman, 1992: 5).

Altman approach is more historical and technological than cognitive. Nevertheless, the conditions of hearing he describes are big challenges to a cognitive theory of cinema. In order to face this new idea of assuming films (and film sounds) as events, I want to propose three lines of inquiry, within the frame work of cognitive semiotics: phenomenology (as a theory of hearing experience); cognitive (empirical) research (particularly on event perception); and agentive semiotics (as a new approach to meaning that emphasizes the intentional, enactive, and embodied location of semiotic agents).

2. Phenomenology of (film) hearing

As Jordan Zlatev notes, “there are multiple schools and types of phenomenology, but the basic idea is to depart from experience itself, and to provide descriptions of the phenomena of the world, including ourselves and others, as true to experience as possible – rather than constructing metaphysical doctrines, following formal procedures, or postulating invisible-to-consciousness causal mechanisms that would somehow “produce” experience” (Zlatev, 2012: 15).

For this particular case is wise to take advantage of what has already been done in the field of phenomenology. Particularly, I want to introduce some of the ideas developed by Don Ihde in his book Listening and voice: Phenomenologies of sound (Idhe, 2007). In this work, Ihde takes as starting point the phenomenology of Husserl in order to describe the way in which sounds appear to the experience: “the invisible is the horizon of sight. An inquiry into the auditory is also an inquiry into the invisible. Listening makes the invisible present in a way similar to the presence of the mute in vision” (Ihde, 2007: 51). We find again the idea of event: “Insofar as all sounds are also ‘events’, all the sounds are, within the first approximation, likely to be considered as ‘moving’.” (Ihde, 2007: 53).

That relates sound with space. As Joel Krueguer notes, “phenomenologically speaking, it appears that auditory experiences are locational. They represent both what is happening (e.g. children playing outside) as well as how what is happening stands in relation to oneself (e.g. slightly behind me and to the left)” (Krueguer, 2011a: 65). In Krueger’s terms, “Listening to sounds is an exploration of our world—including spatial and locational aspects of things in it. Sounds routinely furnish spatial information about our world, and we use our auditory experiences to explore and skillfully respond to things happenings in it. Phenomenologically, sounds are thus spatially structured” (Krueguer, 2011a: 67).

We can also found this idea in Joseph Anderson’s ecological perspective, when he affirms that “Vision tells us where things are in space; hearing tells us when they move. And when they move, we are able to locate them in space” (Anderson, 2007: 27).

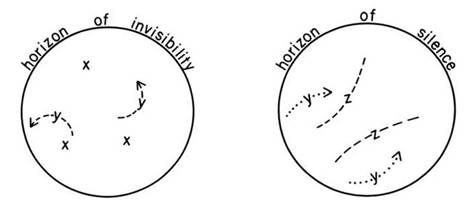

Back to Ihde, this author uses the phenomenological concept of horizon to describe sound and vision. He represents these experiences as two circles: one for the horizon of invisibility from which emerges vision, and the other for the horizon of silence, from which emerges sounds.

Idhe, 2007: 52 |

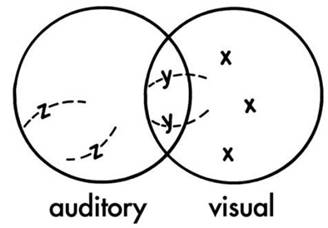

In our experience, the two types of information overlap. The graphic represents this relation: “in the visual field a vast totality of entities that can be experienced. Some are stable (x) and usually mute in ordinary experience. Some others (-y--) move, often “accompanied” by sounds. Beyond the actually seen field of presence lies a horizon of invisibility. And a similar diagram can be offered for a “region” of sound presences. What may be taken as absent for one “region” is taken as a presence for the other. While the area of mute objects (x) seems to be closed to the auditory experience as these objects lie in silence, so within auditory experience the invisible sounds (--z--) are present to the ear but absent to the eye. There are also some presences that are “synthesized” (-y--) or present to both “senses” and “regions”.

Idhe, 2007: 53 |

2.1. The spatial dimension of sound field

According to Ihde, “sounds are frequently thought of as anticipatory clues for ultimate visual fulfillments. The most ordinary of such occurrences are noted in locating unseen entities” (p. 54). The auditory world is then one of “flux” and that it is primarily temporal. Nevertheless, Sounds also manifest it selves in space. Some theorists talks about the “weak” spatially of sounds, because of the difficulty of placing sounds with accuracy. This is way for us sounds are first experienced as sounds of things, even when we are not capable to say “where” exactly they are. To this extent, sounds are also understood as aspects of things: shapes, surfaces and interiors: “in the movement from shape-aspects to surfaces to interiors there is a continuum of significations in which the “weakest” existential possibilities of auditory spatial significations emerge” (p. 71). However, as we point before, there is also a “strong” spatiality in sound experience, and it is related to the phenomenological concept of field:

The question of an auditory field has already been proximately anticipated in the observation that all things or occurrences are presented in a situated context, “surrounded” by other things and an expanse of phenomena within which the focused-on things or occurrences are noted. But to take note of a field as a situating phenomenon calls for a deliberate shifting of ordinary intentional directions. The field is what is present, but present as implicit, as fringe that situates and “surrounds” what is explicit or focal. This field, again anticipatorily, is also an intermediate or eidetic phenomenon. By intermediate we note that the field is not synonymous with the thing, it exceeds the thing as a region in which the thing is located and to which the thing is always related. But the field is also limited, bounded. It is “less than” what is total, in phenomenological terms, less than the World. The field is the specific form of “opening” I have to the World and as an “opening” it is the particular perspective I have on the World (Idhe, 2007: 73).

In film and audiovisual experiences this field has visual and auditory dimensions. The visual field has a forward oriented directionality, relative to bodily position, because of the place of our eyes in front of our heads. As a shape the auditory field does not appear so restricted to a forward orientation. Instead, Sound surrounds me in my embodied positionality: “the auditory field and my auditory focusing is not isomorphic with visual field and focus, it is omnidirectional” (Idhe, 2007: 75).

In that sense, according to Idhe, “the auditory field would have to be conceived of as a “sphere” within which I am positioned, but whose “extent” remains indefinite as it reaches outward toward a horizon”[1]. The surroundability, then, is an essential feature of the field-shape of sound, but it also includes directionality. Both features provide to sound experiences its dynamic aspect. In this respect, Idhe he offers a filmic example: “In 2001: A Space Odyssey, it was found that without the sound of background music the slow drifting of the spaceship did not appear even as movement. The silent movie is accompanied by the piano. The intimate relation between animation, motion, and sound lies at the threshold of the inner secret of auditory experience, the timefulness of sound. The auditory field is not a static field” (Idhe, 2007: 83).

2.2. The temporal dimension of sound field

This example shows the importance of the temporal dimension of hearing to a conception of film sounds as events. Idhe addresses this question from Husserl’s conception of time:

A phenomenology of experienced temporality soon comes on the notion of a temporal span or duration of sounding that is experienced in listening. I do not hear one instant followed by another; I hear an enduring gestalt within which the modulations of the melody, the speech, the noises present themselves. The instant as an atom of time is an abstraction which is related to the illusion of a thing in itself. In terms of a perceptual field we have noted that a thing always occurs as situated within a larger unity of a field; so temporally the use of instant here is perceived to occur only within the larger duration of a temporal span, a living present. Moreover, according to Husserl’s prior analysis (…), this temporal span displays itself as structured according to the onset of features coming into perception, protension, and the phasing and passing off of features fading out of presence, retention. Within the temporal span the continuing experience of a gestalt is experienced as a succession within the span of duration (Idhe, 2007: 89).

However, this version of the temporality of sound experiences must be related to the attentional aspect of listening intentionality that Idhe called the “temporal focus”. As intentional activity, listening can be attached to certain aspects of experience. This “temporal focus” may be narrow, thin or wide, according to the intentionality of the listener. In this perspective, protentions are “empty temporal intentions” which seek access to presence, but it can be achieved or frustrated. The protentions are attentional structures that should be future-oriented.

2.3. Between “field state” and “deep listening”

Idhe also speaks of a particular phenomenon of listening he calls “field state”, when the attentional focus is extended to the entire sensory field. This is the case of certain musical experiences in which the listener's attention is full and open. This is that Krueguer calls deep listening:

…a voluntary form of musical experience consisting of sustained attentional focus and affective sensitivity. It is an immersive form of listening in which the subjectselectively orients herself to a piece of music by actively attending to its various sound features and their interrelationships – while simultaneously maintaining a state of affective receptivity, or a readiness-to-be-moved, by what is happening sonically in the music (Krueger, 2011a: 70 – 71).

It is possible to think that film listening oscillates between regular attentional listening and Deep Listening. That is, of course, because of the presence of music in films, but also because the way in which sound in general is designed to modulate spectator’s experiences. To understand the way in which sound and image interacts in filmic experience, phenomenology could provide a rich set of tools to describe our fluent interface with movies.

3. The cognitive/empirical study of event perception

The second line I want to propose to understand hearing experience in cinema is the empirical study of event perception. One of the main researchers in this field is Jeffrey M. Zacks, the leader of the Dynamic Cognition Laboratory of the Washington University's Department of Psychology. According to Zacks and his colleagues, event perception is the set of cognitive mechanisms by which observers pick out meaningful spatiotemporal wholes from the stream of experience, recognize them, and identify their characteristics. One of the procedures to understand the way in which we perceive events is event segmentation, understood as “a form of categorical perception in which intervals of time are picked out as units and distinguished from other intervals. As such, it is a mechanism of Gestalt grouping: The ongoing stream of activity is parsed into meaningful wholes” (Zacks, 2008: 2).

3.1. Event recognition

Other cognitive operation that people performs every time is event recognition: “in addition to picking out individual events from the behavior stream, observers also recognize events as belonging to classes. Event recognition is closely tied to event segmentation. Individuating events helps to identify them, and identifying events helps to individuate them” (Zacks, 2008: 3). According to Zacks, many categories of events can be identified from motion patterns, but these basic experiences are used to understand more complex human actions.

3.2. Event segmentation theory

Zacks and his colleagues have developed an event segmentation theory (EST), from empirical research: “the perceived structure of events can be measured explicitly by simply asking people to watch movies of everyday events and identify the points at which they believe one meaningful unit of activity ends and another begins. Although these instructions are somewhat vague, there is good agreement, both across and within individuals, as to the point at which one unit of activity ends and another begins, and observers are able to adjust their grain of segmentation in order to identify larger or smaller units of activity” (Zacks, Speer, and Reynolds, 2009: 307).

According to EST, observers form models, called event models, in working memory, which guide the perception of incoming information. These event models permits predictions as to what will occur in the environment, and as long as incoming information is consistent with these predictions, the current event model remains active. When predictions fail, the event model is updated, and the system becomes momentarily more sensitive to incoming information. Once the event model is updated, prediction error falls, and the system falls into a new stable state. The cascade of a transient increase in error, event model updating, and resettling is experienced as an event boundary.

EST also proposes that event boundaries tend to occur when features in the environment are changing, because changes are generally less predictable than stasis. In this point, Zacks et al make a very relevant distinction to us: in reading and film comprehension:

Two broad classes of feature can be distinguished: perceptual features such as movement, color, and sound timbre; and conceptual features such as characters in a story, characters' goals, and causes. There is growing evidence that changes in perceptual features are associated with event boundaries. Observers are more likely to identify an event boundary at points with large changes in movement (Newtson, Engquist, & Bois, 1977), and brain areas involved in the perception of motion are activated at event boundaries (Speer et al., 2003; Zacks, Braver, et al., 2001). More recently, studies in which simple animations were used have provided quantitative evidence that precisely measured movement features, including acceleration, distance, and speed, are excellent predictors of the points at which observers segment activity (Hard, Tversky, & Lang, 2006; Zacks, 2004). The evidence that conceptual changes influence event segmentation is more limited (Zacks, Speer, and Reynolds, 2009: 308).

Thus, as perceptual features sounds are very important in the discretization of events, but also a particular kind of events it selves. Nevertheless, sound features are even more describable as events than other perceptual features like colors or shapes. As Casey O’Callaghan noted, “Sounds, intuitively, are happenings that take place in one’s environment. This is evident in the language we use to speak of sounds. Sounds, like explosions and concerts, occur, take place, and last. Colors, shapes, and fiddles do not” (O’Callaghan, 2007: 57).

So even when certain visual features change according to movement, sounds are always events, always in transformation: “Sounds, that is, appear to relate to space and time in ways characteristic to events. Understanding sounds as events of some sort amounts to a powerful framework for a satisfactory account of both the metaphysics of sound and the contents of auditory experience” (O’Callaghan, 2007: 58). The categorization and segmentation of sound events are, thus, theoretical instruments to understand the general way in which spectators perceive and categorize events in film experience. This has a particular interest to different kind of film and audiovisual productions as abstract films or musical video clips, besides the general trend of narrative movies.

4. Agentive semiotics: intentionality, attention and semiotics scenes

The last trend I want to propose to the study of sound in film experience is a new semiotic theory developed from some of the theories revised here: phenomenology, cognitive semiotics, but also from the central role of the concept of purpose in peircean semiotics. According to Douglas Niño, the main developer of agentive semiotics, significance is produced in the relationship between an agent and her agenda ((Niño, 2013a, 2013b; Niño, 2014, forthcoming). Agency here is understood as the capacity that enables the agent to make sense of something; thus meaning emerge when an agent tries to fulfill an agenda (that is, the type of result that 'point' the agent through his/her action) by exercising her agency (Niño, in press).

Agentive semiotics defines an agent as an embodied, situated and dynamic been that focus her attention in some point of her environment according to the agenda(s) in course. Audiovisual spectator is a particular agent, place in a particular field of experience (as defined before from the phenomenological perspective): a film, a TV broadcast, etc. Nevertheless, if we understand audiovisual productions as experiences of events, perceptual and cognitive activity of an agent oscillates between the experience of “semiotic scenes” (intentional constructions assumed here as a particular type of events) and the experience of her actual world, called the “base scene”, by Niño.

4.1. From “diegetical worlds” to “semiotic scenes”

According to Niño, agentive meaning emerges in a certain place and in certain moment, both constituting the agent’s base scene. But this meaning is about something, a phenomenon also placed in space and time that constitutes her semiotic scene. In the case of audiovisual experience, the place and moment in which spectator perceives the projection or broadcast of any audiovisual production constitutes her base scene, and the technically constructed events that she perceives in the screen and the speakers are hersemiotic scene. However, “as the place and moment ‘in” which meaning emerges could be also the place and moment ‘about’ about we are trying to make sense, as in perception (…) that is to say that base scene and semiotic scene are not different from a phenomenological point of view. The distinction is thus merely methodological: is like the difference between ‘where’ (base scene) and ‘to where’ (semiotic scene)” (Niño, Fortcoming: 255).

With this clarification, Niño just want to say that we use the same cognitive and perceptual abilities to perceive and make sense about movies that we use to the actual experience of the world. The only difference is that in movies (and other audiovisual productions) perceptual information is modulated by someone who wants to manage our attention in a particular way. And, as I tried to show before, sounds are a particular way to build semiotic events, that is, semiotic scenes that modulates spectator’s attention.

Agentive semiotics is a new trend that offers several concepts and theoretical instruments to explore and describe audiovisual phenomena. By integrating to its conceptual frame the developments of phenomenology of hearing and event perception theory I hope to provide a new approach to understand the role of sound in the (multimodal) experience of film spectatorship.

References

ABEL, Richard & Rick ALTMAN, (eds). 2001. The Sounds of Early Cinema. Indiana University Press.

ANDERSON, Joseph. D. 1998. The Reality of Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory. Southern Illinois University Press.

ANDERSON, Joseph. D., Barbara FISCHER, David BORDWELL, et al. 2007. Moving Image Theory: Ecological Considerations. Southern Illinois University Press.

ALTMAN, Rick. (ed.). 1980. Cinema/Sound. Yale French studies (16th).

ALTMAN, Rick. (ed.). 1992. Sound Theory, Sound Practice. New York, Routledge.

ALTMAN, Rick. 2007. Silent film sound. Columbia University Press.

BORDWELL, David. 1987. Narration in the Fiction Film. New York, Routledge.

BORDWELL, David & Nöel CARROLL. 1996. Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies. Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin Press.

BRANIGAN, Edward. 1992. Narrative Comprehension and Film. New York, Routledge.

CASETTI, Francesco. 1999. Theories of Cinema, 1945-1995. Austin, University of Texas Press.

CURRIE, Gregory. 1995/2008. Image and Mind: Film, Philosophy and Cognitive Science. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

CHION, Michel. 1985. Le son au cinéma. Paris, Editions de l'Etoile/Cahiers du Cinéma.

CHION, Michel. 1991. L’audio-vision (son et image au cinéma). Paris, Nathan-Université. (Last edition: Paris, Armand Collin, 2005). (English version: 1994. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. Columbia University Press).

CHION, Michel. 1998. Le son, traité d'acoulogie. Paris, Nathan-Université (Last Edition: Paris, Armand-Colin, 2005).

CHION, Michel. 2003. Un art sonore, le cinéma. Paris, Cahiers du Cinéma. (English version: 2009. Film, a Sound Art. Columbia University Press).

Fontanille, Jacques. 2011. Corps et sens. Paris, Presses Universitaires de Frances.

GRODAL, Torben. 1999. Moving Pictures. A New Theory of Film Genres, Feelings, and Cognition. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

GRODAL, Torben. 2009. Embodied Visions. Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

IHDE, Don. 2007. Listening and voice: Phenomenologies of Sound. State University of New York Press.

JULLIER, Laurent. 1995. Les sons au cinéma et à la télévision : Précis d'analyse de la bande-son. Paris, Armand Colin.

JULLIER, Laurent. 2002. Cinéma et cognition. Paris, Editions L'Harmattan.

JULLIER, Laurent. 2012. L'analyse de films : De l'émotion à l'interprétation. Paris, Editions Flammarion.

KRACAUER, Siegfried. (1997 [1960]). Theory of Film. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

KRUEGER, Joel. (2013). “Empathy, enaction, and shared musical experience”. In The Emotional Power of Music: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Musical Expression, Arousal and Social Control, eds. Tom COCHRANE, Bernardino FANTINI & Klaus R. SCHERER. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 177-196.

KRUEGER, Joel. 2011a. “Enacting musical content”. In Situated Aesthetics: Art beyond the Skin, ed. Riccardo Manzotti. Exeter: Imprint Academic: 63-85.

KRUEGER, Joel. 2011b. “Doing things with music”. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 10.1: 1-22.

MAGLIANO, J.P. & J.M. ZACKS. 2011. “The impact of continuity editing in narrative film on event segmentation”. Cognitive Science, 35, 1-29.

METZ, Christian. 1971. Langage et cinéma. Paris, Larousse. (English version: 1974. Language and Cinema. The Hague: Mouton).

METZ, Christian. 1974. Essais sur la signification au cinéma tome 1 et 2. Paris, Klincksieck (English version: 1990. Film language: a semiotics of cinema. University of Chicago Press).

NIÑO, Douglas. 2013a. “Agentes y circunstancias. Consideraciones en torno a factores epistémicos y fiduciarios en la argumentación intercultural”. In Cuatro aproximaciones al diálogo argumentativo intercultural. Bogotá, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano.

NIÑO, Douglas. 2013b. “Signo peirceano e integración conceptual: una propuesta de síntesis”. In Ensayos Semióticos II. Semiótica e integración conceptual. Bogotá, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano.

NIÑO, Douglas. (Forthcoming). Elementos de semiótica agentiva. Bogotá, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano.

NUDDS, Matthew & Casey O’CALLAGHAN. (eds). 2009. Sounds and Perception. New Philosophical Essays. Oxford University Press.

O’CALLAGHAN, Casey. 2007. Sounds. A Philosophical Theory. Oxford University Press.

SONESSON, Goran. 2009. “The View from Husserl’s Lectern. Considerations on the Role of Phenomenology in Cognitive Semiotics”. Cybernetics and Human Knowing. Vol. 16, Nos. 3-4. p. 25 – 66.

ZACKS, Jeffrey. M. 2008. “Event perception”. Scholarpedia, 3, 3837.

ZACKS, Jeffrey. M. & J. P. MAGLIANO. 2009. Film understanding and cognitive neuroscience. In D. P. MELCHER & F. BACCI (eds.). New York: Oxford University Press.

ZACKS, Jeffrey. M., Nicole SPEER & Jeremy. R. REYNOLDS. 2009. “Segmentation in reading and film comprehension”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 138, 307-327.

ZACKS, Jeffrey M. 2010. “How we organize our experience into events”. Psychological Science Agenda, 24.

ZACKS, Jeffrey M., C.A. KURBY, M.L. EISENBERG & N. HAROUTUNIAN. 2011. “Prediction error associated with the perceptual segmentation of naturalistic events”.Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23, 4057-4066.

ZLATEV, Jordan. (2012). “Cognitive Semiotics: An emerging field for the transdisciplinary study of meaning”. In http://konderak.eu/materialy/Zlatev_2012.pdf

[1] From another perspective, French semiotician Jacques Fontanille have propose to conceive the “sensory field of hearing” also as a “sphere”, but more like a “bubble”, in the sense that a bubble can be deformed, extended; that is to say, it is a flexible shape, as it is our hearing experience (Fontanille, 2011: 68 – 69).