VIRTUAL AND PHYSICAL AESTHETICS OF THE HUMAN BODY–WITH REFERENCE TO THE FASHION DESIGNS OF JEAN-PAUL GAULTIER

Université Paris 8, France

Abstract

In his work, the human body is often both abstracted and concretized. These strong, opposite expressions are present simultaneously. “Abstraction” means human body represented as numerical/digital information while “concretization” means vivid existence in a real, physical sense. Today, the human body seems to be becoming an increasingly informational object. People have very detailed numerical knowledge about the body. In addition, technological developments allow us to construct our body image in a way similar to androids or robots: an ensemble of complicated wire circuits transmit electrical signals to be integrated into a central part like a brain. When it comes to the perception of heat, for example, people can comprehend according to a specific color shown on a thermometer’s screen. Virtual images settle progressively in our mind. “Skin Series”, where Gaultier used three identical models, illustrate clearly this observation. Each piece represents muscle, blood vessels and bones. His illustration shows a kind of simplification to figure these organs and everyone will understand what he represents. However, in spite of their closeness, these organs will never be visually familiar to us. Our awareness is drawn to them only during specific occasions like an accident or an injury. Advanced medical knowledge and detailed anatomical knowledge have given us a typical human body image. In short, a reconstructed body through new technologies is very different from a real body, accompanied with smell, perspiration and weight.

Furthermore, Gaultier is one of the first couturier to appoint atypical/untraditional fashion models. Today, the an unusual body seen on the catwalk no longer causes sensation because we have become accustomed to this kind of surprise, seeing various models, large, small and different. However, at the time Gaultier first introduced this idea, it caused a scandal amongst the conservative realm of Haut Couture. Certainly, there are many variations on the form of the human body. Gaultier dressed a man of rough structure in his finest feminine dress. He put the finest lace stockings on well-muscled masculine calves.

What I attempt to theorize in my presentation is the modern relationship between virtual image and the true, physical human body in order to understand the reality of contemporary fashion concerning body consciousness and physical perception.

1. Introduction

Jean-Paul Gaultier, born in 1952, French Haute Couture and Pret-a-Porter couturier, never received formal training for his profession. His diverse, innovative, provoking fashion, radically confronts critical issues in conventional Haut Couture. Unfortunately, his works have been misunderstood and incorrectly evaluated partly due to his excessively provocative slogans. The revaluation of his designs and creations concerns his manner of representing the human body which radically influence our body consciousness.

In his work, the human body is often represented as both an abstract object and a concrete figure. These strong, opposite expressions are present simultaneously. The “abstraction” of the human body refers to a stylist’s use of numerical/digital information or virtual images to represent the flesh while its “concretization” refers to a vivid representation of a real, detailed, physical existence. Today, the human body seems to be becoming an increasingly non-subjective object but an “objective” one thanks to very detailed numerical and biological information about the body. Along with this vast knowledge, technological developments allow us to construct images of the human body way similar to those of androids or robots.

Jean-Paul Gaultier is one of the first couturiers to appoint atypical or untraditional fashion models. Today, an unusual body seen on the catwalk no longer causes sensation because we have become accustomed to this kind of surprise, seeing various models, large, small and different. However, at the time Gaultier first introduced this idea, it caused a scandal amongst the conservative realm of Haut Couture.

In my presentation, I attempt to decode the modern relationship between virtual image and the true, physical human body in order to understand the reality of contemporary fashion concerning body consciousness and physical perception.

2. Who is Jean Paul Gaultier?

Jean Paul Gaultier was the creative director of Hermès from 2004-2010. Born in a modest family in a suburb of Paris, he lived with his parents and grandmother who gave him an initiation into couture during his childhood. Through his grandmother, he discovered the corset and was inspired to create the famous design: “cone-shaped bra” (Figure 1.). In 1971, he started working as an assistant of Pierre Cardin who was deeply impressed by his sketches. He presented his first individual collection in 1976 (aged 24), and another one in 1981. His revolutionary success impacted fashion. Since then, he has been known as the “enfant terrible”[1] of not only French Fashion but also in international fashion context. Jean-Paul Gaultier collections are inspired by street wear, popular culture, striptease, sadomasochism, etc., deviating completely from the formality or normality of conventional Haute Couture's, thus, celebrating the outsider.

Beyond the apparent eccentricity of his creations, there are other, more interesting characteristics notable in his style: an original portrayal of the beauty of human body. Liberated from standards, far from convention, he plays with it, jokingly, sometimes even transforming human body into something absurd, not sophisticated, ridiculous, nonsensical, unstylish even bad-looking!

Traditionally, fashion has been an ardent pursuit of the absolute ideal human body. The infinite study and insistent effort to achieve this ideal is called “fashion”. From this point of view, Jean-Paul Gaultier’s creation is contrary to all norms in traditional fashion. This deviation holds great meaning, his artistic expression opened a door toward possible new representations that liberate the human body from all kinds of existing stereotypes.

3. “Cone Bra”: Abstraction of the human body

In Jean-Paul Gaultier’s creations, the designer radically transforms the body into a completely unrealistic form. One of the most famous examples is the cone-shaped bra. This costume was beloved by Madonna (Figure 2.). She appeared in a cone-shaped bra during her “Blond Ambition Tour”[2] in 1990. The unrealistic form resembles an android robot, far from being “sexy” in the usual way. Madonna in this nude pink corset, accentuating feminine body parts, was absolutely provocateur for spectators, triggering fashion’s most legendary moments. This corset with a cone-shaped bra was first presented in Jean Paul Gaultier’s Autumn/Winter collection in 1984.

Gaultier is known for being one of the first designers to appoint plus-sized models or untraditional models on his catwalk. Beth Ditto[3], American singer-songwriter, author-interpreter, well known for her activities with the indie rock band Gossip, was appointed as fashion model for the Jean Paul Gaultier collection Spring/Summer 2011. The presence of Beth Ditto in the show was definitely a standout moment. She appeared on the catwalk wearing a black mid-length dress, the breasts covered with delicate pink lace and small flowers, shaped like the cone-shaped bra corset. Her performance surprised conservative amateurs of fashion, opening up a new road toward more creative rendering of the human body. The appointment of Beth Ditto was significant not only for showing the designer’s favour for “plus-sized” or “untraditional” models but also displaying his open-minded attitude toward LGBT: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender, and feminist, too. (Figure 3.)

Eve Salvail, Quebecois, born in 1973, was also appointed by Gaultier as his model. Several years after abandoning modeling, Gaultier ushered her back into the European fashion world in 1992. He shaved her head and tattooed a Chinese dragon on it. Salvail reappeared on the catwalk in a heavenly corseted temple dress fastened tightly her torso, using the opportunity to come out as a lesbian. The public was shocked.

What is the purpose of appointing “atypical” mannequins such as Beth Ditto, Eve Salvail or even male models in women’s fashion shows, adorning them in dresses and other traditional feminine garments? Why did he dress such diverse models in the same cone-shaped bra corset? We can understand his decision to dress various bodies in the same costume as a kind of homogenization of body image despite the undeniable diversity in real human body shapes. Each different body can be prepared as uniform and homogeneous ones. Jean-Paul Gaultier’s purpose was to focus on representing strikingly diverse bodies with one “universal” body image using the human body as a “media”.

4. Living fashion mannequins: Concretization of the human body – Scenography of the Jean-Paul Gaultier exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery, London (2014)

At the Barbican Art Gallery in London this year, an exhibition titled “The fashion world of Jean Paul Gaultier from the sidewalk to the catwalk”[4] featured 32 mannequins coming to life with interactive faces created by high-definition audio-visual projections. Featured among these 32 “living” mannequins, are the voices and faces of Eve Salvail (model), Melissa Auf der Maur (bass player) and Gaultier himself. These collaborators lent their faces and voices (speech and song) for this innovative scenography project. (Figure 4.) Rambling through the exhibition to survey presented works, visitors’ attention was overcome by the mannequins’ “living” faces, brought to life by fixed video-projectors; especially that of Gaultier himself, which engaged onlookers with his personal commentary on the exhibition. When the visitors walked through the exhibition space, the scenography gave a strange impression. Compared with exhibitions where artists show their works on certain “immobile” or “fixed” supports, these “living” mannequins can in effect become an obstacle because they strongly attract visitors’ attention, sometimes enough so that they pay much less attention to the designs on display. According the designer's statement, he did not want to use neutral, identical, “immobile” supports to show his works. Rather, he hoped to stage his creations in a living context; as if real human bodies were wearing them.

In my opinion, the significance of this scenography characterized by spatial and video-projector usage for audio-visual effect is, first, the “differentiation” or “detachment” (Brecht’s distanciation) of “identical” fashion mannequins’ bodies. Jean-Paul Gaultier also provoked the stereotypical fashion models body image: thin, sophisticated and homogeneously standardized. Fashion models, walking on catwalk, have a standardized look and perfect body-line. His intention of projecting real faces on identical fashion mannequin heads means, secondly, his challenge. Throughout this scenography, Jean-Paul Gaultier demonstrated that we can make up a neutral, prototypical body without specific features to appear different, original, unique.

In the fist argument concerning the costume cone-shaped bra corset, Jean-Paul Gaultier showed a kind of “homogenization” of body image beyond the diversity of human body shape. The second argument about a scenography with “living mannequins” concerns the “differentiation” of fashion mannequins’ identical bodies in order to concretize and distanciate as if each individual owns a different body. Now, we observe the third point of view, referring to Gaultier’s two creations about human body representation and body consciousness.

5. “Skin series” and “Nude dress”: Virtualization of the human body – Flesh wearing flesh, the body wearing bodies: body tights[5]

5.1. “Skin series” (Figure 5.)

Three, tight, separate printed costumes represent muscle, blood vessels and the skeleton. The costume representing muscle is coloured by realistic shades of red and orange flesh, while those of blood vessels and heart (coloured red) and bones (coloured black and white) are illustrated in a pop-art manner. Using the pop-art manner, each tight costume shows a different layer of human body. His representation of the inside of our body stirs up typical virtual/digital images we meet constantly in our daily life.These images can be seen in anatomical illustration books, at medical examinations, or on computer screens such as in tridimensional animations and games. These printed tights emulate body and tattoo arts from all over the world. This garment allows us to wear a kind of second skin on our real skin. What was Gaultier's real intent in representing several diverse inner layers of the body as a second skin?

These tights turn our bodies inside-out, exposing muscle, blood vessels and skeleton. These costumes may be considered as a kind of transparent cloth exposing what is inside. However, I would like to regard the effect as “turning inside-out”. Kiyokazu Washida[6], Japanese philosopher, gave an interesting explanation about the effect of the cloth turning inside-out, referring to Yohji Yamamoto[7]’s cloth design in the 1990s. Kiyokazu Washida theorized on the meaning of wearing cloth that “turns inside-out” in terms of our body consciousness from the point of phenomenological view. The clothes created by Yohji Yamamoto in the 1990s, usually black, provoking stereotypical beauty norms in fashion, carved his way in deviating from the main stream of fashion kingdom. Certain jackets and pullovers were turned inside-out, exposing any sewing traces which generally are well-hidden. Concerning the act of wearing clothes, Washida explained that the inner side of cloth directly contacts our body/skin while the outer side works as protector against the outside world. According to him, turning our clothes inside-out means exposing our corporal “intimacy” toward the “exterior” society. The role of cloth is therefore overturned. However, in my opinion, Gaultier's design goes beyond this case. These tights expose human's muscle, blood vessels and skeleton, which are clearly much more intimate than skin because they are located in the internal body. But, this intimacy is a just a “mask”. The muscle, blood vessels and skeleton are painted, numerically designed and printed on the material. What we see on them is a kind of “general” organ image or the interior image of human body. Wearing these tights, in reality, doesn’t mean the exhibition of our own interior, nor our intimacy, but allows us to put on a “general” model of the inside of human body. Their images are virtual and can potentially belong to anyone, all human beings.

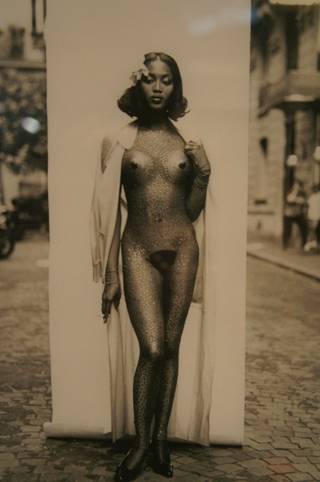

5.2. “Nude dress”[8] (Figure 6. & 7.)

Look at another creation of Jean-Paul Gaultier, that is, the nude dress that could go as far as making us feel ashamed when we imagine ourselves in it. It is a series of tight-fitting dresses, with illustrations of nipples, omphalos and pubic hairs on their surface. Human beings, as highly civilized animals, dress themselves for the purpose of covering the intimate parts of our body. Showing in public once again these hidden intimate parts should cause sensational confusion. However, Gaultier could respond to the ordinary public’s reaction by saying that the intimacy here is virtual, not real, and that his costumes are a representation of visualized body image as well as a humorous illusion… That is why “Nude dress” plays an important role in the consideration about the relationship between the act of wearing and body image.

Here, we can apply the same way of thinking as previously in the “Skin series”. In short, these “Nude dress” are prepared as a kind of a suit of armor, which makes your own body invisible by covering completely with a “ready-made nude”. The nude exposed in public doesn’t belong to anyone. Those who wear this costume do not have to feel ashamed because it does not show their body, nipples, omphalos or pubic hairs. This means a representation of a “typical” nude, not a particular one but “universal” one.

6. Conclusion: escape from the self or self-representation of “inter-subjectivity”

Practicing fashion or costume wearing is a way of self-representation via our own body. For carrying out this self-representation (fashion), we have to be responsible for our own body; we have to care for it, maintain its good condition, exercise it, etc. All we have to do, from head to toe, can be exhausting.

Jean Paul Gaultier proposes an alternative point of view for fashion as a self-representation via the human body. Wearing a costume featuring many different layers of the internal body, in the inside-out manner (observed in the tight costume “Skin series”), or enveloping the body with the painted “Nude dress” (which plays a role of armor to protect our real existence against the society), nullifying the variety of body shapes by shoving them into the same corset (observed in “corn-shaped-bra” costume) or revealing a fact about human body’s homogeneity and its potential for transformation by projecting images on identical fashion mannequins' heads, does Jean-Paul Gaultier reveal the true meaning behind his innovative fashion creations ?

Everything Gaultier did throughout these trials is a kind of sublimation of the body image as a universal object.

Wearing garment as a way of self-representation is based on our individual body as media. The art of Gaultier offers us an alternative way to enjoy ourselves in fashion. Individuals can obtain metaphysical and universal images of human body. The designer may say that the media (human body) does not have such an importance but it can easily be turned out, modified, deformed, made invisible or visible and even nullified, thanks to the art of fashion.

Paradoxically, Gaultier’s fashion creations are not self-representations but representation of inter-subjectivity. Playing with the possible appearance of human body, the designer constructs the “universal” image, which confronts stereotypical and shared understandings. After consideration, the act of wearing clothes, that is, the practice of fashion, is free from all restrictions and negative judgements of the body (“ugly”, “unsophisticated”, “ungraceful”), but fashion becomes an activity permitting a liberated body consciousness in order to sublimate the individual body image as a “universal” one.

We know that some of Jean-Paul Gaultier’s creations are radical and that his costumes do not seem like realistic clothes for the majority of fashion amateurs. Why did he create these absurd garments? For what purpose did he intend them? The act of expression carried out by a fashion designer is in a dilemma. Although the creation of a designer is considered his own artistic expression, when he presents his works, it is not through his own body that the designer carries out his exhibition, but through the medium of fashion mannequins’ bodies. The self-representation in Jean-Paul Gaultier’s creations is “distanciated” and “differentiated”, transforming into a kind of sharable expression for those who appreciate them. They benefit from the simple joy of wearing the designs thanks to a universalized body-image, free from self-consciousness.

Illustrations:

Fig. 1: Shirred velvet strapless dress with cone-shaped bra cups, Women's prêt-à-porter autumn/winter 1984-85.

Fig. 2: Madonna's cone-shaped bra.

Fig. 3: Beth Ditto's costume.

Fig. 4: Exhibition's Scenography, London, 2014.

Fig. 5: Skin series.

Fig. 6: Naomi Campbell in front of the Cabaret Michon, Rue des Martys, Women's prêt-à-porter spring/summer 1993.

Fig. 7: Nude dress.

References

Books (authored work):

PONTY, Merleau. 1945. Phénoménologie de la perception [Phenomenology of perception]. Paris: Gallimard

PONTY, Merleau. 1961. L’œil et l’esprit [Eye and mind]. Paris: Gallimard

WASHIDA, Kiyokazu. 1995. Chiguhagu na kawada: Fasshon tte nani ? [The unfashionable body: What is tthe fashion?]. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo.

WASHIDA, Kiyokazu. 1997. Hitoha naze fuku wo kirunoka: Bunka-sochi toshite no fasshion [Why we wear?: The fashion as cultural device]. Tokyo: NHK ningen daigaku tekusuto.

WASHIDA, Kiyokazu. 1989. Modo no meikyu [Labyrinth of the fashion]. Tokyo: Chuokoron-sha.

WASHIDA, Kiyokazu. 1989. Saigo no modo [The last fashion]. Kyoto: Jinbun Shoin.

WASHIDA, Kiyokazu. 1998. Himei wo ageru karada [Our crying body]. Kyoto: PHP shinsho.

Book (edited work):

JASS (Japanese Association for Semiotic Studies). 2014. Krukoto/Nugukoto no kigoron [Semiotics of wearing and taking off]. Tokyo: Shinyo-sha.

Contribution in an edited work:

OKUBO, Miki. 2013. Vanitas, Hiroshi Ashida & Daijiro Mizuho, Gyakko suru sintai hyosho [Body representation going backward], 155–168.

[1] The surname “terrible child” is due to his “different” professional career, whereby he passed through many traditional maisons, with a radical attitude and an ignorance of Haute Couture world’s conventions. He turned fashion creation upside down, surprising his clientele.

[2] “Blond Ambition” is a tour carried out by Madonna in 1990. During this acclaimed four month tour, Madonna gave fifty-seven concerts in twenty-seven cities all over the world.

[3] Beth Ditto, born in 1981, is an American singer and song-writer. Feminist and lesbian, Beth Ditto shows her militant attitude for contesting social conventions, and for the freedom of sexuality, especially for homosexuality.

[4] This retrospective exhibition took place from April 9 to August 25 in 2014, in the Barbian Art Gallery of London.

[5] Body tight is a tight covering entirely the body.

[6] Kiyokazu Washida, Japanese philosopher and phenomenologist, is author of many books concerning philosophical analysis of the vestment and the act of wearing clothes.

[7] Yoji Yamamoto, Japanese fashion designer, is famous for his creations of the street fashion style, especially by the usage of black. He created many vestments “too large and too long”, “damaged” or “inside-out”.

[8] Nude dresses are garments which are designed as if the person wearing them were nude. These dresses show nipples, omphalos and even pubic hairs on their surface.