THE VALUE OF EDUCATION IN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS’ ADVERTISEMENTS: A VISUAL SEMIOTICS-BASED MIXED METHOD RESEARCH APPROACH.

George Damaskinidis

The Open University, UK

Anastasia Christodoulou

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Abstract

Our research studies the meaning structures of international organizations’ objectives regarding how education is defined and makes connections and correlations about the way in which education’s objectives and vision are promoted through images. We examine how international organizations treat the objectives of culture and education as vehicles for values in the pictures and texts of their advertisements. By means of a mixed research method combining socio-semiotics, multimodality and visual methodologies, we focus on exploring the vision for education, as this is shown in international organizations’ advertisements. We approach the advertisements as social artefacts, in the form of multimodal texts, where the investigation of their social meaning involves the juxtaposition of their semiotic elements on the same interface. We direct our analysis towards a critical visual methodology where images are taken seriously, their social conditions and effects are addressed, and viewer reflexivity is promoted. This mixed method facilitates the exploration of the diverse ideological representation of education in international organizations’ advertisements. However, this methodology is at an early stage of development and requires additional elaboration and extensive applications. Also, an in-depth study needs to be made of the relevant theoretical background of any previous attempts to combine the three different methods.

1. Introduction

The subject of values, culture and education has been dealt with by numerous academics both diachronically and synchronically. In this research effort, we make a similar attempt to combine these three areas by designing a mixed-method research model to study the meaning structures of international organizations. In particular, we look at the ways in which education’s objectives and vision are promoted through print and audio-visual advertisements. We examine how international organizations treat the objectives of culture and education as vehicles for values in the pictures and texts of their advertisements. By means of a mixed research method combining socio-semiotics, multimodality and visual methodologies, we focus on exploring the vision for education, as this is shown in international organizations’ advertisements.

We direct our analysis towards a critical visual methodology where images are taken seriously, their social conditions and effects are addressed, and viewer reflexivity is promoted. This mixed method facilitates the exploration of the diverse ideological representation of education in international organizations’ advertisements. The reason for combining three different models, that is, isotopies, image-text relations and metafunctions (as shown later), is to allow us to research a single phenomenon from three different perspectives while taking advantage of the similar theoretical and methodological approaches. The complexity of this endeavour has been a challenge for us for several years now, and we are not without awareness of the slippery research paths we are about to follow.

The article begins with the overall theoretical framework, and in particular, with our visual sociosemiotic perspective, the three components of the model, that is, the concepts of isotopy, image-text relations and metafunction. We then move on to the presentation of the development of the mixed-method model. After that, we make an attempt to validate the mixed-method model, which includes a very brief note from our experience of putting this model into practice with postgraduate students. We conclude this article with an overall evaluation of the proposed mixed-method model and the limitations it poses for future research.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. A visual and sociosemiotic perspective

The visual semiotic perspective that has been adopted here is governed by the fact that the visual is a social research process. Jewitt and Oyama’s (2001) theoretical investigation of the concept of ‘semiotic mode’ is based on social semiotics. This theoretical approach investigates human signifying practices in specific social and cultural circumstances (Lagopoulos and Boklund-Lagopoulou, 1992). The method allows viewers to create their own interpretations and interconnections about visual material. At the same time, it creates windows on the world and offers subjective points of view, which are socially determined.

This perspective is possible if we move away from pure language and adopt the concept ofsemiotic mode. This would require a broadening of traditional views about language. Linguists, for example, have started to realize that verbal language may not be adequate by itself to discuss the various intersemiotic relations between certain verbal and non-verbal aspects of multimodal texts, such as the translation of humour in film and comics. Hortin (1994) supports the validation of visual language within a visual literacy framework and argues for the establishment of an analogy between verbal and visual language. However, despite the foregrounding of semiotic elements other than language in the production of modern texts, the fact that “most Western societies remain print dominated” (Hull and Nelson, 2005: 2) makes any effort to discuss non-verbal modes of communication a difficult task.

The semiotic explorations of the visual are made within social contexts, and in particular, the advertising world. This socio-semiotic method analyses the advertisements beyond a formalistic approach and treats them as integral parts of a material, socio-economic and political context. In order to accomplish these explorations, we have adopted three main theoretical and methodological concepts: Greimas’ (1996) isotopies, Barthes’ (1977) image-text relations and Kress and Van Leeuwen’s (2006) metafunctions.

2.2. Isotopies, image-text relations and metafunctions

The perspective described in section 2.1 underpins theoretically the three-pillar model that consists of the concepts of isotopy (Greimas, 1996), image-text relations (Barthes, 1977) andmetafunction (Kress and Van Leeuwen, 2006).

Isotopy is a key term in sociosemiotics supported by Greimas (1996) who, since the late 1960s, has been the central figure in the Paris School of Semiotics. Adopting a theory of structural semantic isotopy, we could describe the coherence and homogeneity of different multimodal texts in order to find the isotopies in these texts and thus detect when there is a repetition of a basic meaning trait (seme). In advertisements, for example, this would involve the examination of the verbal message and any accompanying visual material, such as a photograph. Such a repetition, which establishes some level of familiarity within the texts, would allow readers to find if there is a uniform reading/interpretation of them. In this case, the focus would be to bring to light potential ways that the polysemous photographs are disambiguated or complicated by the co-occurrence of the captions.

Barthes (1977) presents an interesting semiotic reading of an advertisement and some photographs, in terms of image-text relations. He illustrates that there are three messages, or three levels, of signification to the analysed semiotic text: the linguistic or informational; the coded iconic or symbolic; and the non-coded iconic or obtrude. At the first level, everything is clearly given; there is a clarity and immediacy in the image and the information it provides. At the second level, we deal with symbolism, but since there are different kinds of symbol, the signification is more complex, giving rise to different interpretations. At the third level, things are entirely different; the viewer or reader is confronted with indeterminate, undecidable meaning, a place of presence and absence. There is no natural relationship between image and its meaning, and what furnishes the image with connotations is metonymy. The syntagm of denotation naturalizes or legitimates the system of the connoted message, bringing disparate, discontinuous and unrelated connotations into a concerted whole.

A similar three-stage analysis is provided by Kress and Van Leeuwen (2006), consisting of the representational, interpersonal and compositional metafunctions. Briefly speaking, the representational metafunction presents narrative and conceptual images which examine what the picture is about. The narrative image represents the unfolding of actions, events or processes of change in terms of the people, places or things depicted. Conceptual images do not represent the participant as doing something, but as being something, meaning something, belonging to some category, or having certain characteristics or components. The interpersonal metafunction deals with the image’s act/gaze, social distance and intimacy, and perspective to examine how the picture engages the viewer. The compositional metafunction deals with the layout of the picture, the placement of the participants and its relative salience. This metafunction examines how the representational and interpersonal metafunctions integrate into a meaningful whole. The placement of participants on the page allows them to take on different information roles. Salience refers to the ability of a participant to capture the viewer’s attention. Modality is an indicator of the message’s validity and reliability, in terms of various visual factors.

The above three, briefly presented concepts are considered here as three distinct models which could be combined in various ways so as to make up a mixed methodological model. The next section describes our exploration of such a mixed model which would choose selectively, from the range of the options offered by each model, without being constrained by conflicting factors, such as the different epistemological stances.

3. Developing a mixed-method research methodology

According to Onwuegbuzie and Leech (2005), most current educational research runs along a continuum between the postpositivistic and the constructivist paradigms. According to Burgess et al. (2006: 54), a paradigm is “a set of beliefs that deals with ultimates and first principles [and] presents a world-view that defines for its holder the nature of the “world”, the individual’s place in it, and the range of possible relationships in that world”. Many researchers, according to Rossman and Wilson (1985), still believe that studies (and as such their methodological basis) need to be situated in either a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Here, we work against the polarization that methodologies cannot be mixed (Howe, 1988) and that epistemology dictates the method of data collection or analysis (Cohen et al., 2007). We view this research from a unified perspective where the research question drives methodological approaches/choices. We also cite ‘pragmatic researchers’ who are flexible in their research techniques and collaborate with other researchers with multiple epistemological stances (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2005). This methodology is in fact an ongoing process that requires prolonged engagement, persistent observation, and triangulation (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2005).The research is approached mainly (though not exclusively) from different paradigms, such as post-positivism, interpretivism and postmodernism.

The post-positivism paradigm accepts that an absolute model is difficult to establish, but it could still strive for objectivity while combining quantitative and qualitative methods of data-collection and analysis. From an interpretivistic perspective, any model can be studied and interpreted in different ways, mainly because people and situations differ. The postmodernism paradigm seeks to break down conventional boundaries and draw attention to how permeable and movable they can be. Taking into account the post-positivist perspective, we acknowledge that it would be difficult for the researcher who uses a mixed model to establish a definitive reading of the phenomena examined. However, some degree of objectivity could be gained through a combination of research methods, in other words, through triangulation, that some readings are more likely than others. By adopting an interpretivist approach, researchers could be allowed to interpret for themselves the phenomena under investigation. Moreover, a postmodernist approach would facilitate the breaking down of the conventional boundaries between the three models by drawing researchers’ attention to the permeability and mobility of these boundaries.

The semiotic square extends the binary models of Saussure and his followers, such as Claude Levi-Strauss (1983), into the realm of anthropology, by providing a means of mapping semiotic dimensions in four rather than two dimensions. Beginning with the binary opposition of two values, such as male/female or for self/for others, the researcher can explore the grey areas between these extremes by introducing an operation of negation: not male/not female, not for self and not for others. By superimposing a plurality of binary oppositions including gender, relationships and emotional orientation, the semiotic square provides a more nuanced and refined grid for mapping consumer segments and brand meanings than the simple paradigmatic opposition of two dimensions. Floch (1990/2001) later applied Greimas’ theory to illustrate the double layer of signification in the picture, namely iconic and plastic levels, in order to explain how concrete or abstract concepts are transmitted by the picture. Floch (1990/2001), applying structural semiotics, further argues that pictorial signification exists and plays a role in the structure of binary opposition.

Adopting the research method of Lagopoulos and Boklund-Lagopoulou (1992), who studied the notion of isotopy on the verbal and visual levels, we approach the advertisements as social artefacts, in the form of multimodal texts, where the investigation of their social meaning involves the juxtaposition of their semiotic elements on the same interface. In this way, both the verbal and the non-verbal semiotic elements are studied as an integrated system of communication, and as such all meaning-making modes are treated equally when assessing their contribution to multimodal texts.

Although Kress and Van Leeuwen’s (2001) visual grammar is a useful tool, its application requires careful consideration. For instance, the interpretation of a multimodal text based on this visual grammar should bear in mind whether the text was also designed and produced on the basis of the same visual grammar. The same applies in cases of cross-cultural communication, especially between Western and non-Western cultures.

Type of Model | Stages-Components | Distinctive Feature |

Greimas’ isotopies | repeating patterns verbal and non-verbal semiotic elements | homogeneity and coherence of texts |

Barthes’ image text relations | linguistic/informational coded iconic/symbolic non-coded iconic/obtrude | levels of signification |

Kress & Van Leeuwen’s metafunctions | representational interactive compositional | visual grammar |

Table 1: Delimiting Barthes, Greimas and Kress & Van Leeuwen.

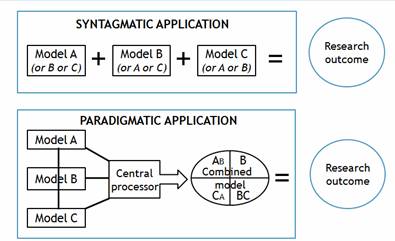

Table 1 shows the various components that make up the proposed mixed model, which a researcher could choose from in order to analyse a text. In figure 1 we can see our suggestion for the two main ways of applying the mixed model, in other words, the syntagmatic and paradigmatic application modes.

Fig. 1: Syntagmatic and paradigmatic application of the mixed model.

In the syntagmatic mode, the three models are applied consecutively, where the application of the preceding model will unavoidably affect the application of the following one. The research outcome will be the result of the analysis of Model C, as affected (as applicable) by Models A and B. In the paradigmatic mode, the researcher takes into account the three models, all at the same time, and after careful consideration decides to use a combined model consisting of several stages.

For the sake of illustration, we will describe the combined model consisting of stages AB, B, CA or BC. AB stands for a stage where the researcher applies Model A in its entirety and an aspect of Model B. CA stands for a stage where the researchers apply Model C in its entirety and an aspect of Model A. BC stands for a stage where the researchers apply both Model B and C in their entirety. B stands for a stage where the researchers apply only Model B because they have deemed it the most appropriate for the analysis of the phenomena at hand. The last case is an example of the freedom offered to researchers to abandon any consideration of combining the models for a variety of reasons. However, the fact that researchers would have been involved in this brainstorming may actually affect the application of a single model. In addition, the combination of different models for examining a single phenomenon may not only be time-consuming but may also lead to conflicting interpretations of the same phenomenon.

4. Validating the mixed-method analytical model of the concept of value in education

In order to evaluate such a mixed research approach, we propose the validation framework put forward by Leech, et al. (2010). This framework consists of five elements: the foundational element; the elements of construct validation for quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research; inferential consistency; the utilization/historical element; and the consequential element. Due to space constraints, this framework will not be presented in theoretical detail, but will instead be illustrated in a small-scale study we carried out as part of a postgraduate course.

4.1. Description of the study of value as an educational advertising product

Mixed research methods were used to study the impact of reading videos and print advertisements on postgraduate students. The advertisements had to be about international organizations and how they promote their education values. However, since the students had difficulty finding appropriate educational advertisements, or they did not like this particular topic, we modified this criterion and allowed them to choose their own topic, as long as the advertisement was made by an international organization. For example, some students chose advertisements on human rights, environmental protection and public health.

We gave students some examples of semiotics-based postgraduate assignments from previous courses of ours and asked them to choose the one they liked the most, or to combine them, as applicable. The students provided a very brief review of the literature at the beginning of the assignment and focused on the analysis of the advertisements. The analysis was to be guided by the values each organization held (either in education or another topic) and the ways in which these values were fulfilled and promoted by the educational product (e.g. a video, a single print advertisement, a campaign).

Although students were instructed to analyse them using all three models in any way they liked, most of them used only one or two models. It should be stated that their training in these models was not thorough enough to enable them to combine the models in a variety of ways. That said, their training was sufficient for the purposes of this project.

4.2. Evaluation of the proposed mixed-method model using the validation framework

First, the foundational element of construct validation should be addressed. In terms of the level of quality and the function of providing a review of the literature in this study, it addresses theoretical issues related to all three models as well as issues that are related to their design in the present literature. These issues are used to make arguments about and support the purpose of the study. One area that is not covered sufficiently in the review is the literature addressing conflicting epistemological and ontological aspects of the three models.

Second, as regards the traditional quantitative and qualitative elements, the model offers opportunities for the examination of factors such as design, measurement, sampling and data analysis. For example, the design would account for the order of the various components. Measurements would include the number of isotopies identified in relation to the non-verbal semiotic elements of a metafunction or level of signification. Elsewhere, internal validity would be examined by inferring that the relationship between verbal and non-verbal semiotic elements in the interactive metafunction is causal owing to the absence of repeating patterns due to lack of homogeneity of the texts under analysis. A single researcher could analyse the qualitative data of the symbolic level of signification as opposed to the symbolic conceptual aspect of the representational metafunction. This stage of analysis could possibly compensate for the lack of a team of researchers or independent external auditors.

Third, the mixed-method elements may lead to a design that would be appropriate for the purpose of the study at hand. For example, a sequential approach could be used, with emphasis placed on the initial qualitative stages that would provide results for use in instrument development. However, there are some issues about various types of legitimation, such as sequential legitimation. For example, the sequence of the qualitative and quantitative stages of the model would not necessarily result in the same findings if the order was reversed. In addition, the sample size may also be an issue because it could lead to an imbalance between the amount of qualitative and quantitative elements used, as opposed to those needed, for each different model.

Fourth, the analysis of inferential consistency would include an examination of the way the different elements of the study flow to lead to the inferences that are made by the researchers, and the purpose, design, analysis, and inferences of the literature review. The three models may require different measures of qualitative and quantitative analysis. This imbalance may make the translation of qualitative results into quantitative measures, or vice versa, appear inadequate. Additionally, a number of measures of items (e.g. reporting the analyses, factor analysis and regression results) may not be correlated. One possible way to overcome this obstacle is to identify a data-text or corpus that would be appropriate for all three models. However, this identification would be possible only after numerous experimental applications of the three models to a variety of texts.

Fifth, the historical/utilization element would help to determine how the study results and measures will be used in the future. For example, the data obtained by a mixed-method model with a certain structure could be directly applied and analysed by another model with a different structure. This is important in cases where the researcher would show a preference for playing with the data in an attempt to analyse and investigate the same phenomena from various points of view.

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to demonstrate the application of a new methodological framework to assist researchers in conducting mixed research studies. As shown in this article, the mixed-method model is also a flexible tool for researchers to use when needing to evaluate mixed research studies.

The benefit of conducting research with this model is its flexible approach to investigating a single phenomenon from multiple points of view. The model incorporates multiple areas of a study for a researcher to use, including the concepts of isotopy, image-text relations and visual grammar. In addition, it is open to additions from other epistemological, theoretical and methodological areas.

Also, as a mixed research study, the model lends itself to the validation framework proposed here. As expected, each application of the model will differ in the way it will be designed and implemented. Therefore, for each study, one evaluator from each model may be required to make sure that all aspects of the mixed research model are thoroughly examined.

There are also two main limitations to our proposal for a mixed research model. First, applying the proposed model to a given study may be difficult, or simply not feasible, especially for novice researchers, such as postgraduate students. The fact that the latter were not properly introduced to this mixed-method model, though they were more or less familiar with the three distinct models, may be an indication that the model’s overall effect is greater than the sum of the meaning of the three different models. Second, a detailed rendering of the students’ application of the mixed-method model was not possible because of space limitations and our wish to focus on the presentation of the model per se.

References

BARTHES, Ronald, 1977. Image-music-text. S. Heath, translator. Glasgow: Fontana.

BURGESS, Hilary; Sandy SIEMINSKI & Lore ARTHUR, 2006. Achieving your doctorate in education. London: Sage.

COHEN, Louis; Lawrence MANION & Keith MORRISON, 2007. Research methods in education(6th ed.). New York: Routledge.

FLOCH, Jean-Marie, 1990/2001. Semiotics, marketing and communication: Beneath the signs, the strategies. R. O. Bodkin, translator. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave.

GREIMAS, Algirdas Julien, 1966 (1983). Structural semantics. Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press.

HORTIN, John A., 1994. ‘Theoretical foundations of visual learning’. In: David Mike MOORE & Francis M. DWYER (eds.), Visual literacy: A spectrum of visual learning, 5–29. Englewood Cliffs: Educational Technology Publications.

HOWE, Kenneth R., 1988. ‘Against the quantitative-qualitative incompatibility thesis or dogmas die hard’. Educational Researcher 17(8). 10-16.

HULL, Glynda A. & Mark Evan NELSON, 2005. ‘Locating the semiotic power of multimodality’.Written Communication 22 (2). 1–38.

JEWITT, Carey & Rumiko OYAMA, 2001. ‘Visual meaning: a social semiotic approach’. In: Theo VAN LEEUWEN Theo & Carey JEWITT (eds.), Handbook of visual analysis, 134–156. London: Sage.

KRESS, Graham & Theo VAN LEEUWEN, 2006. Reading images – The grammar of visual design(2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

LAGOPOULOS, Alexandros & Karin BOKLUND-LAGOPOULOU, 1992. Meaning and geography: the social conception of the region in northern Greece. New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

LEECH, Nancy L.; Amy B. DELLINGER; Kim B. BRANNAGAN & Hideyuki TANAKA, 2010. ‘Evaluating mixed research studies: A mixed methods approach.’ Journal of Mixed Methods Research 4(1). 17-31.

LEVI-STRAUSS, Claude, 1983. The raw and the cooked. John and Doreen Weightman, translators. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

MICK, David Glen & Laura R. OSWALD, 2006. ‘The semiotic paradigm on meaning in the marketplace’. In: BELK (ed.), Handbook of qualitative research methods in marketing, 31–45. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

ONWUEGBUZIE, Anthony J. & Nancy L. LEECH, 2005. ‘On becoming a pragmatic researcher: The importance of combining quantitative and qualitative research methodologies’.International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 8. 375–387.

ROSSMAN, Gretchen B. & Bruce L. WILSON, 1985. ‘Numbers and words: Combining quantitative and qualitative methods in a single large-scale evaluation study’. Evaluation Review 9. 627–643.