“CON-FUSION CUISINES”: MELTING FOODS AND HYBRID IDENTITIES

University of Turin, Italy

simona.stano@gmail.com

Abstract

The expression “fusion cuisine” is generally used to refer to a style of cooking combining ingredients and techniques from different foodspheres. Asian fusion restaurants, for instance, offer blends of various cuisines of different Asian countries and the culinary traditions of the places where they have become increasingly popular. Similarly, the Tex-Mex cuisine combines the South-western United States culinary system with the Mexican foodsphere, while the Pacific Rim cuisine is based on the mix of different traditions from the various island nations; and so on and so forth. In all these cases, foods based on one culinary culture are prepared using ingredients, flavours, and techniques inherent to another culture. Consider for instance the case of “Taco Pizza”, a pizza made with cheddar and pepper jack cheese, tomato sauce, refried beans and other common taco components; or that of the so-called “fusion-sushi”, including several variations of rolling makiwith different types of rice and ingredients, such as curry and basmati rice, cheese, tomato sauce,raw meat, etc. According to the etymology of the word fusion, the main feature characterising fusion cuisine could be described in terms of a harmonious combination of different culinarytraditions in order to create innovative and seamless dishes. This has important implications not only on the material side, but also and most importantly with respect to the sociocultural sphere and the symbolic dimension. Far from simply coinciding with material needs or physiological and perceptive processes, nutrition concerns all the various activities, discourses, and images that surround and are associated with it, becoming a form of expression of cultural identity. Sometimes, however, fusion cuisines run the risk to degenerate into “con-fusion cuisines”, causing inevitable clashes between incompatible flavours and textures, and fomenting a chaotic overlapping between different foodspheres and “food identities”. While novelty is certainly commendable, restraint and continuity are also important. The same concepts of tradition and innovation, moreover, are complex and multifaceted, and need to be further analysed and discussed. Building on the analysis of some specific case studies, chosen for their relevance within the wide range of examples of fusion cuisine, we aim at addressing such issues and investigating the processes of translation between different substances, sensorialities, and eating experiences, focusing on the negotiation of the sense of food in specific situations.

1. What is fusion food?

The expression “fusion cuisine” is generally used to refer to a style of cooking combining ingredients and techniques from different foodspheres.[i] Asian fusion restaurants, for instance, offer blends of various cuisines of different Asian countries and the culinary traditions of the places – especially the United States and Europe – where they have become increasingly popular. Similarly, the Tex-Mex cuisine combines the South-western United States culinary system with the Mexican foodsphere, while the Pacific Rim cuisine is based on the mix of different traditions from the various island nations; and so on and so forth. In all these cases, foods based on one culinary culture are prepared using ingredients, flavours, and techniques inherent to another culture. Consider for instance the case of “Taco Pizza”, a pizza made with cheddar and pepper jack cheese, tomato sauce, refried beans, taco chips, lettuce, and other common taco components. Or that of the so-called “fusion-sushi”, including several variations of rolling maki with different types of rice and ingredients, such as curry, basmati rice, cheese, sauce, raw meat, etc.

But how do the processes of “fusion” between different substances, sensorialities, and eating experiences take place? How is the sense of food negotiated in these situations? And how can we describe such processes in semiotic terms? This paper aims at addressing these issues, building on the analyses of specific case studies chosen for their relevance within the wide range of examples of fusion cuisine.

2. Two case studies: Wok’n roll and Fuzion in Turin (Italy)

Building on previous research (Stano 2014), we decided to deal mainly with sushi, taking into considerations two specific case studies: Wok’n roll and Fuzion in Turin (Italy). Open in 2010, Wok’n roll is ranked among the best noodle and sushi bars in Italy, providing customers with restaurants where they can enjoy food, as well as with takeaway and delivery services. The same facilities are offered by Fuzion, which opened its doors in 2014, combining the Italian cuisine with sushi and other dishes typical of the Eastern foodspheres.

2.1. Wok’n roll

Wok’n roll’s menu – which can be found both at the restaurant and on its website – immediately reveals the predominance of fusion cuisine in the dishes available at the “noodle and sushi bar”.

Fig. 1: Wok’n roll’s menu (first page).

Specifically, fusion emerges on two levels: the map at the bottom of the page (fig. 1) introduces the reference to different Asian countries, namely the places where the foods used in the menu come from. This first level of fusion is reiterated by the figures in the right-bottom, evoking a Vietnamese cook and a Japanese waitress, as well as by the figurative elements on its top (i.e. drawings of a statue of the Buddha, a Malaysian tiger, the Itsukushima Shrine and the Mount Fuji in Japan, the Hạ Long Bay in Vietnam, the typical Asian hibiscus flowers, and other common elements referring to Asian culture and settings). The logo introduces a second level of fusion, recalling the Western world. The same could be said for the text, which makes explicit reference to the Italian foodsphere: “Oltre al pesce crudo proponiamo anche rolls con prestigiosi prodotti made in Italy. Avevi mai pensato a un sushi roll con la salsiccia di Bra oppure con il Parmigiano in tempura?” [In addition to raw fish we offer rolls made of excellent Italian products. Have you ever imagined a sushi roll containing Bra sausage or Parmesan tempura?, our translation.]

Fig. 2: Wok’n roll’s menu (second page – detail).

Actually the restaurant offers two main types of food products to its guests: as regards to woks, people are able to customise their meal through a three-step process: the choice of (i) the type of pasta and of (ii) the sauce is characterised by the same first level of fusion described above, since all these products refer to one or more Asian culinary traditions. On the contrary, the third step, consisting in choosing (iii) other ingredients and toppings, introduces the second level of fusion, as it includes elements such as Parmesan and other fresh local products.

With sushi, things radically change. First of all, modularity disappears, and costumers are asked to delegate the know-how-to-do they were provided in the case of noodles to the restaurant itself, choosing among the several already set options listed in the menu.

Fig. 3: RIPLEY (on the left) and MEDITERRANEO (on the right) rolls.

Figure 3 shows the RIPLEY (on the left), which is a roll made of rice, raw meat (“cruda di vitello”, which is very popular in Piedmont, the region where Turin is located), lettuce, tempura Parmesan, taggiasca olives (which are typical from Liguria), and lime sauce (substituting the commonly used soy sauce). On the right, we can see the MEDITERRANEO roll, made of sushi rice, Tempura local vegetables, fried mozzarella (which is a typical Italian cheese) and strawberry aromatic vinegar.

Fig. 4: GALA GALA rolls.

Finally, the GALA GALA (Fig. 4) contains the famous sausage from Bra, usually eaten raw, lettuce, arugula, Parmesan and lime sauce, with an external layer of coloured soy paper (instead of the more common nori).

In these and other cases, different Asian cuisines are mixed (i) among each other and (ii) with the Italian foodsphere. What is more, the extreme variability characterising the Italian cuisine emerges, making reference to different regional traditions. It is also very interesting to note that actually the only unchanged element with respect to the source foodsphere (namely the Japanese one, where sushi is thought to have originated) is the shape or form in which such a food is served. This is what, building on Hendry’s works (1990a, 1990b, 1993), we (Stano 2014) proposed to describe in terms of a “wrapping structure”, that is, a specific configuration of concentric layers reflecting many aspects of Japanese aesthetics and thought. Attention is paid mainly to maintain such a structure, while ingredients are considered as perfectly interchangeable among each other, provided that they are “shaped” in the right way.

2.2. Fuzion

The visual identity of the restaurant plays a crucial role also in the case of Fuzion. The logo (fig. 5) is particularly interesting: first of all, focusing on the lettering, the inversion of the “N”seems to suggest the idea of reversibility. Both the O, recalling the well-known Japanese calligraphic art, and the initial F, evoking the shape of a shrine or temple, refer to the Japanese semiosphere. The use of green could also be interpreted as a reference to the Japanese culture and the importance it confers to nature (cf. Stano 2014 and in print). Moreover, polychromy suggests the idea of variety. However, the uniformity of the second and third lines stresses complementarity, as the verbal text clearly states: “ASIAN AND MEDITERRANEAN MELTING FOOD.”[ii]

Fig. 5: Fuzion’s logo.

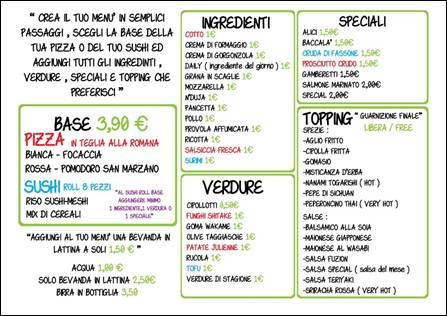

With respect to the menu (fig. 6), modularity embraces in this case also sushi. People are invited to create their own menu, through a two-step process always recalling the previously mentioned second (or third, if we consider also the reference to the Italian regional cuisines)-level process of fusion.

Fig. 6: Fuzion’s menu (second page – extract).

Costumers can choose their favourite base for pizza (plain or with tomato, but always in the typical Roman type “by the slice”) or sushi (with rice or mixed cereals) and then add their favourite ingredients (vegetables, toppings, and sauces). More extended sections, however, provide consumers with already set options for “traditional” or “fusion” pizza and sushi (which, although erroneously, is always referred to as uramaki, regardless of its actual configuration, generally actually coinciding with hosomaki[iii] or futomaki[iv]).

Fig. 7: CRI CRI, BUFFALO BILL, JULIA ROLL, CHICKEN TAGGIASCHE and SMOKE SABArolls.

Figure 7 shows the CRI CRI roll, which is made of sushi rice, raw meat, cheese cream, one fresh local vegetable (chosen among the available options by costumers), arugula, “Japanese mayonnaise”, and tempura grains. BUFFALO BILL contains sushi rice, buffalo sausage, cheese cream, lettuce and citronette. The JULIA ROLL includes carne salada (i.e. marinated meat typical from Trentino), Parmesan, arugula, truffle cream (since truffles are also typical from the North of Italy, especially Piedmont), and citronette. In CHICKEN TAGGIASCHE roll mixed cereals substitute rice, and Asian spices and sauces are used. Finally, the SMOKE SABA roll includes also the typical Sicilian tomato (ciliegino di Pachino) and smoked mackerel. In all these cases, moreover, nori is generally substituted by thin coloured soy paper, and rice is short grain but grown in Italy.

Fig. 8: SALMON JAP pizza.

Finally, at Fuzion, fusion extends to pizza. Among the various cases that can be cited, figure 8 shows the popular SALMON JAP pizza, which is made of a plain base with marinated salmon, soy aromatic vinegar, gomasio[v] and goma wake[vi] on the top. Exactly as for Wok’n roll, both in this case and as regards to the previously analysed sushi rolls, no matter which ingredients are used and “melt”, provided that the typical structural configuration of foods remains unaltered.

3. Conclusion

According to the etymology of the word fusion (from Latin fusus, past participle of fundere, “to pour, to melt”), the main feature characterising fusion cuisine could be described in terms of a harmonious combination of different culinary traditions in order to create innovative and seamless dishes. Modularity is in this sense crucial, because, as previously discussed, it highlights the possibility of creating several combinations with specific ingredients introducing different layers of fusion. These combinations have important implications not only on the material side, but also and most importantly with respect to the sociocultural sphere and the symbolic dimension. Far from simply coinciding with material needs or physiological and perceptive processes, nutrition concerns all the various activities, discourses, and images that surround and are associated with it, becoming a form of expression of cultural identity (cf. Barthes 1961; Lévi-Strauss 1965; Montanari 2006; Pezzini 2001). While novelty is certainly commendable, therefore, restraints and continuity are also important. This is where the importance of pre-set fixed options emerges, stressing the role of the providers (namely, the addressers) of the eating experience as regards to the competence – i.e. the previously mentioned know-how-to-do – required to establish such combinations.

Making reference to a well-known model mainly used in linguistics but afterwards expanded to other domains of knowledge, we could describe the “food continuum”, intended as an amorphous sequence of ingredients that can be used to create different combinations, in terms of expression-purport (Hjelmslev 1943). Through the existence of an expression-form (which exists by virtue of being connected with a content-form and which organises the expression-purport), such expression-purport is formed into an expression-substance, that is, a specific sequence of ingredients. The expression-form, therefore, can be described in terms of the models or rules by which specific combinations are carved up and selected from all the possible associations. Building on these considerations, what can be said about these models or rules with respect to the here considered cases? What are the dynamics carving up the analysed “fusion” combinations? The previously described cases seem to stress the importance of mechanisms that, adopting a Greimasian terminology, we could describe in terms of lie or illusion (Courtés 1976; Greimas 1989): de-composing foods in unitary constituents, they claim to replace them with elements from other foodspheres, provided that the general structural configuration of food remains unaltered. In other words, the functioning mechanism of the considered examples is “it seems sushi, but it is not”, “itseems pizza, but it is not”, and so on and so forth. But how could a lie generate the euphoric state and positive sanction expected in the case of fusion foods eaten at restaurants? How could these mechanisms enhance curiosity instead of provoking disgust? In other words, how can they foster innovation instead of causing rejection?

A first point requires us to consider the intrinsic nature of the eating experience, which does not rely on depth and funded knowledge, but rather on superficial curiosity and simulation. As Franco La Cecla (1997), Roland Barthes (1961) and other scholars remind us, food can be considered an easily crossable frontier, where alterity assumes the form of an exotic and “palatable” experience. Such an experience is always based on simulation, since even what is presented as authentic and traditional is itself the result of an internal look somehow imitating the external look whose “taste” it has to match. This is why food seems particularly compatible with such “lying mechanisms”, which introduce elements of innovation by hiding them under already established forms of expression. Normalisation processes thereafter make novelty slowly become part of tradition, and what is unknown become part of what is known and usual.

This recalls Giulia Ceriani’s distinction (2004) between contamination and fusion. Building on the dictionarial definition of these concepts, the Italian semiotician distinguishes them on the base of the semantic opposition “multiplicity/uniqueness”. Favouring the first pole in this opposition, contamination works by juxtaposing and putting together different elements, therefore making all the constituents of the final object recognisable – even though, the sense arises only from the union of these elements, as in any form of bricolage (Lévi-Strauss 1962; Floch 1986, 1990, 2006). Fusion favours instead the second pole of the opposition, opting for the nomination of a new object replacing those that gave origin to it. Whilst the first case establishes a sort of equilibrium among the different elements assembled together, the latter is characterised by a substitution creating a new form through the elimination of the pre-existing ones, without leaving any trace of this process. Continuity therefore replaces in this case discontinuity, and conjunction supplants disjunction, reducing the polyphonic heterogeneity of contamination to the hierarchized structure of components obtained through fusion. After describing these models, Ceriani identifies fashion with contamination, and food with fusion.

By contrast, the previously analysed examples seem to partially contradict such a classification, pointing out the “lying” mechanisms underlying fusion cuisines and the crucial role played in them by discontinuous structural configurations. It seems to us that this contradiction can be explained by making reference to Landowski’s model (1997) for the description of the interactions between identity and alterity. According to the French scholar, with assimilation the Other is disqualified as a subject: “its” singularity does not refer to any formal identity and its alterity is reduced to one’s own identity, so that it can be integrated into the environment by “absorbing” it. Such a process of standardisation and “ingestion” of the Other by the Self is strongly centripetal, leading Landowski to describe it in terms of a conjunction of identities. On the contrary,exclusion denies the Other as such through confinement and elimination, not in a reasoned connection (as in assimilation), but in a more passionate relationship. The shared feature of these two configurations is that otherness, faced with a referential consistent identity, is always conceived as a threatening difference coming from the outside. However, unlike assimilation, exclusion is based on a centrifugal movement, implying a disjunction of identities. In segregation (non-conjunction), the Other is recognised in spite of “his” difference, but still with a fundamental ambivalence between the inability to assimilate him and the refusal to exclude him. Only admission(non-disjunction) leads to a permanent construction of a multicultural collective subject, since differences are in this case attested and accepted, promoting a real encounter between identity and alterity.

Even though exclusion and segregation are in any case excluded – since the consumption of the meal at the restaurant always implies the establishment of a contract proving customers’ openness (or at least their curiosity) toward alterity – admission is not compulsory. Research (Greco and Zittoun 2014; Greco in press) has shown that home-cooked ethnic foods tend to favour the establishment of multicultural collective subjects unceasingly reshaping food grammars by replacing pre-existing units with new foods resulting from their combination – leading to what Ceriani would properly call “fusion” cuisines. By contrast, in all the observed cases, the conjunction between different foodspheres is reduced to assimilation, since otherness is “ingested” by the local Self and curbed into the previously described “lying” structures. The negotiation of the sense of food between and across different foodspheres is in these cases reduced to simple structural models, disregarding the essential synesthetic nature of the eating experience. In fact, eating implies diverse sensorialities, which are just partially subjective and physiological, and mainly intersubjective and socially determined (cf. Perullo 2008). Therefore, the sensorial and cultural specificity of the eating experience makes it impossible to reduce it to simple processes of de-structuration and de-composition of foods in individual unities considered as interchangeable among themselves. This is precisely where the importance of the delimitation of possible ingredients or combinations – that is, the centrality of the addresser of the eating experience – arises, as we previously discussed. But it is also where a fundamental, still open issue emerges, running the risk to leave a bad taste in the mouths of fusion foods’ promoters: to what extent fusion cuisines really enhance sensorial and cultural share and encounter? And to what extent, by contrast, don’t they risk degenerating into “con-fusion cuisines”, causing inevitable clashes between incompatible flavours and textures, and fomenting a chaotic overlapping between different foodspheres and “food identities”?

References

ASHKENAZI, Michael & Jeanne JACOB. 2000. The Essence of Japanese Cuisine. An Essay on Food and Culture. Hampden Station, Baltimore: University of Pennsylvania Press.

BARBER, Kimiko. 2002. Sushi. Taste and Technique. London: DK Publishing.

BARTHES, Roland. 1961. “Pour une psychosociologie de l’alimentation contemporaine”. Annales ESC XVI (5): 977–86. Paris [English Translation 1997. “Toward a Psychosociology of Contemporary Food Consumption”. In Carole COUNIHAN & Penny VAN ESTERIC (eds.).Food and Culture: A Reader, 20–27. New York and London: Routledge].

CERIANI, Giulia. 2004. “Contaminazione e fusione nella tendenza contemporanea: da modalità interoggettive a forme di vita”. EC, http://www.ec-aiss.it/index_d.php?recordID=100 (last accessed: 23/12/2014).

COURTES, Joseph. 1976. Introduction à la semiotique narrative et discursive. Paris: Hachette.

DEKURA, Hideo, Brigid TRELOAR & Ryuichi YOSHII. 2004. The Complete Book of Sushi. Singapore: Periplus Ed.

DETRICK, Mia. 1981. Sushi. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

FLOCH, Jean-Marie. 1986. “Lettre aux sémioticiens de la terre ferme”. Actes sémiotiques (Le Bulletin) IX(37): 7–14.

FLOCH, Jean-Marie. 1990. Sémiotique, marketing et communication. Sous les signes, les strategies. Paris: PUF [English Translation 2001. Semiotics, Marketing and Communication:Beneath the Signs, the Strategies, New York: Palgrave MacMillan].

FLOCH, Jean-Marie. 2006. Bricolage. Lettere ai semiologi della terra ferma. Rome: Meltemi.

GRECO, Sara & Tania ZITTOUN. 2014. “The trajectory of food as a symbolic resource for international migrants”. Outlines – Critical Practice Studies 15(1): 28–48.

GRECO, Sara. In press. “The semiotics of migrants’ food: between codes and experience”.Semiotica. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

GREIMAS, Algirdas Julien. 1989. “The veridiction contract”. New Literary History 20(3): 651–660.

HENDRY, Joy. 1990a. “To Wrap or Not to Wrap: Politeness and Penetration in Etnographic Inquiry”. Man 24: 620–635.

HENDRY, Joy. 1990b. “Humidity, Hygiene, or Ritual Care: Some Thoughts on Wrapping as a Social Phenomenon”. In Eyal BEN-ARI, Brian MOERAN & James VALENTINE (eds.).Unwrapping Japan, 11–35. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

HENDRY, Joy. 1993. Wrapping Culture: Politeness, Presentation, and Power in Japan and Other Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

HJELMSLEV, Louis. 1943. Omkring sprogteoriens grundlæggelse. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard. [English Translation 1963. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

HOSKING, Richard. 1995. A Dictionary of Japanese Food: Ingredients & Culture. Tokyo–North Clarendon–Singapore: Tuttle Publishing.

LA CECLA, Franco. 1997. Il malinteso. Rome–Bari: Laterza.

LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude. 1962. La Pensée sauvage. Paris: Plon [English Translation 1966. The Savage Mind. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press].

LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude. 1965. “Le triangle culinaire”. L’Arc 26: 19–29 [English Translation 1997. “The Culinary Triangle”. In Carole Counihan and Penny Van Esteric (eds.). Food and Culture: a Reader, 28–35. New York and London: Routledge].

LOWRY, Dave. 2005. The Connoisseur’s Guide to Sushi: Everything You Need to Know about Sushi. Boston: Harvard Common Press.

MINISTRY of Foreign Affairs of Japan (MOFA). 2012. Niponica – Delicious Japan 8. Tokyo.

MONTANARI, Massimo. 2006. Food is Culture: Arts and Traditions of the Table. New York: Colombia University Press.

MOURITSEN, Ole G. 2009. Sushi: Food for the Eye, the Body & the Soul. New York: Springer.

PERULLO, N. 2008. L’altro gusto. Saggi di estetica gastronomica. Pisa: ETS.

PEZZINI, Isabella. 2006. “Fluidi vitali: dalla bile nera allo champagne. Note sull’immaginario alcolico-passionale”. In Paolo Bertetti, Giovanni Manetti and Alessandro Prato (eds.),Semiofood. Comunicazione e cultura del cibo. Centro Scientifico Editore: Turin.

STANO, Simona. 2014. Eating the Other. A Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code. PhD Thesis. University of Turin and Università della Svizzera Italiana.

STANO Simona. In press. Eating the Other. Translations of the Culinary Code. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

ZSCHOCK, D. 2005. The Little Black Book Of Sushi: The Essential Guide to the World of Sushi.New York: Peter Pauper Press, Inc.

[i] The term foodsphere (firstly introduced in Stano 2014) is here used to make reference to the concept of “alimentary semiosphere”, therefore stressing the inherently cultural and semiotic nature of the food system.

[ii] It is also worthwhile to remark that, unlike Wok'N Roll, Fuzion provides customers with both chopsticks and the common Western cutlery, allowing them to choose their favourite tool, also depending on the type of food they choose to eat.

[iii] Hosomaki (細巻, “thin rolls”) is a small (0.8-1 in / 2-2.5 cm in diameter) cylindrical piece, with nori on the outside, generally containing only one filling (cucumber – Kappamaki –, raw tuna – Tekkamaki –, kanpyō, avocado, or sliced carrots or cucumber). For more detailed information, see Detrick 1981; Hosking 1995; Ashkenazi and Jacob 2000; Barber 2002; Dekura, Treloar and Yoshii 2004; Lowry 2005; Mouritsen 2009; Zschock 2009; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2012.

[iv] Futomaki (太巻, “thick, large, or fat rolls”) is a large (2-2.5 in / 5-6 cm in diameter) cylindrical piece, wrapped in nori, often made with two, three, or more fillings chosen for their complementary tastes and colours. For more detailed information, see Detrick 1981; Hosking 1995; Ashkenazi and Jacob 2000; Barber 2002; Dekura, Treloar and Yoshii 2004; Lowry 2005; Mouritsen 2009; Zschock 2009; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2012.

[v] Gomasio (ごま塩) or gomashio is a dry condiment made from unshelled sesame seeds (ごま, goma) and salt (塩,shio). It is often used in Japanese cuisine, sometimes being sprinkled over plain rice or on sushi.

[vi] Edible seaweeds.